If I see one more “perfect” portrait on my Instagram feed, I might scream. You know the type – airbrushed skin, symmetrical eyes, lighting that looks calculated by a machine (because, increasingly, it is). It’s technically flawless. It’s marketable. And it is completely, utterly dead. We’re living in the age of the algorithm, where AI generators churn out millions of uncanny, beautiful faces every day, driving down commission prices and forcing artists like me to spend 70% of our week making TikToks just to remind the world that human hands still exist.

But here’s the secret that the tech bros don’t understand: Perfection isn’t art. It’s data. If you want to paint something that actually breathes, you need to stop trying to make it pretty. You need to learn how to paint like Francis Bacon.

Youll Learn

- Francis Bacon revolutionized portrait painting by focusing on psychological truth rather than physical beauty

- Distortion and asymmetry in Bacon’s work reveal emotional states that perfect portraiture cannot capture

- Understanding Bacon’s techniques helps modern artists combat AI-generated “perfect” art

- Visceral painting methods emphasize raw emotion over technical perfection

- Heavy-body acrylics provide the control needed to create Bacon-inspired expressive work

- Contemporary portrait artists can apply Bacon’s principles to create authentic, emotionally powerful paintings

Who Was Francis Bacon and Why Does He Matter Today?

Francis Bacon (1909-1992) stands as one of the most influential British artists of the 20th century. Unlike the Renaissance masters who focused on idealized beauty, Bacon painted the human condition in its rawest, most visceral form. His work shows screaming popes, contorted figures, and faces that seem to melt off the skull—not because he couldn’t paint traditionally, but because he chose not to.

Understanding 20th century art movements helps us appreciate why Bacon’s work was so revolutionary. While many modern artists explored abstraction, Bacon remained committed to the figure—he just refused to make it pretty.

The Historical Context of Francis Bacon’s Work

Bacon began his serious painting career in the 1940s, emerging during a time when Abstract Expressionism dominated the art world. While Jackson Pollock dripped paint and Mark Rothko created color fields, Bacon stubbornly painted people—but not the way anyone expected.

His most famous works, like “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion” (1944) and the screaming pope series inspired by Velázquez’s portrait of Pope Innocent X, shocked audiences. They still do. These paintings don’t comfort viewers; they confront them with the uncomfortable truths about human existence—pain, fear, isolation, and mortality.

Understanding Francis Bacon’s Approach to Beauty

The Anatomy of a Scream

The first time I really saw a Bacon figure, it wasn’t a portrait of a person—it was a portrait of a nervous system. Bacon didn’t care about the Renaissance ideals I find so tedious. He didn’t care if the nose was centered or if the skin looked like porcelain. He cared about the meat. He cared about the scream.

His paintings operate on a fundamentally different principle than traditional portrait painting techniques. Where most portraiture aims to flatter, Bacon aims to excavate. His figures twist, blur, and fracture because that’s what faces actually do when experiencing genuine emotion.

Structure Over Surface: What Bacon Teaches About Facial Anatomy

Bacon famously said, “I would like my pictures to look as if a human being had passed between them, like a snail, leaving a trail of the human presence.” This philosophy fundamentally rejects the idea that a portrait should be a static, perfect representation.

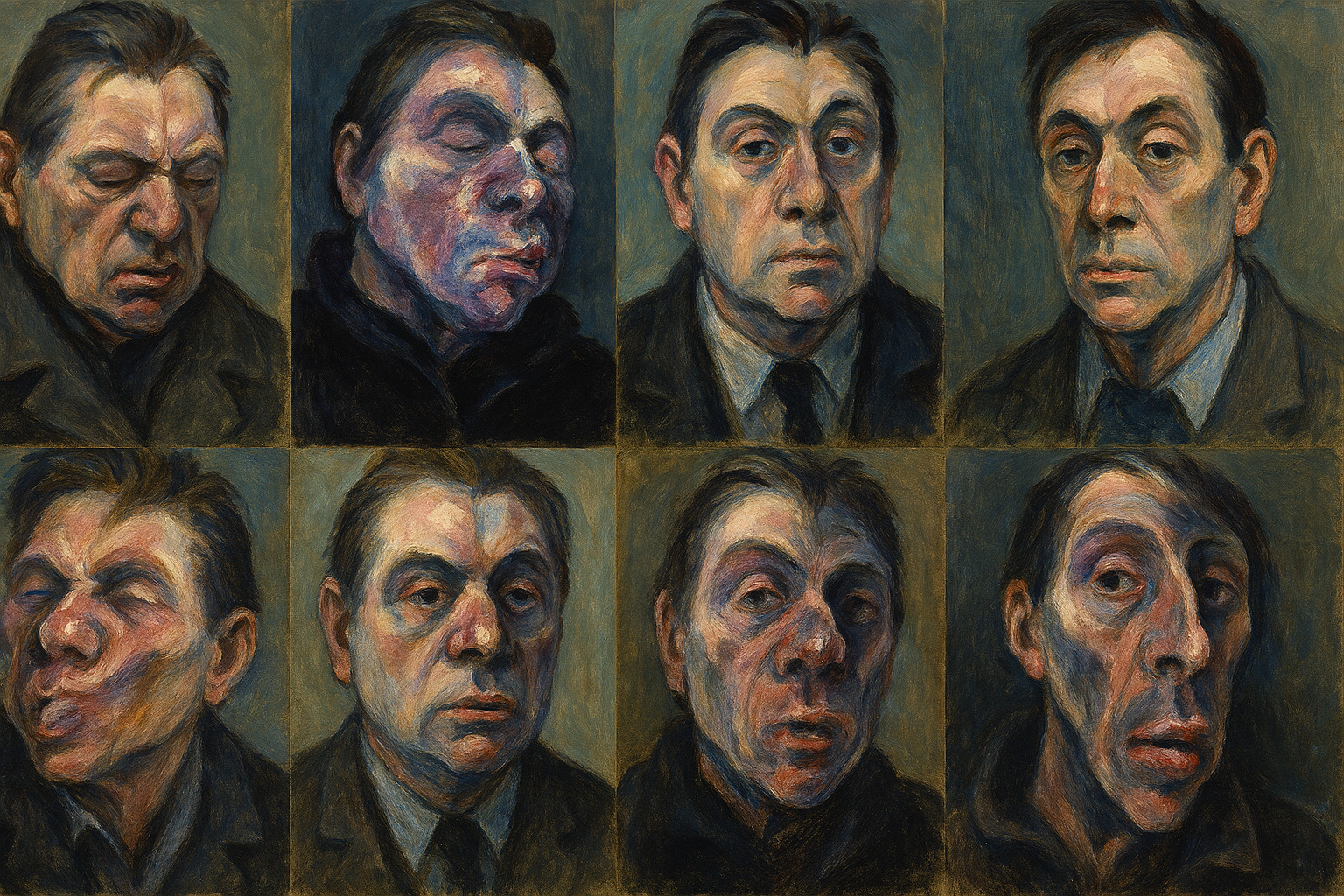

When examining different art types and styles, Bacon’s work stands apart because it treats the face as a mask barely containing the skull, muscles, and psychological turmoil beneath. He studied Eadweard Muybridge’s sequential photographs of bodies in motion and medical textbooks showing disease and decay. These weren’t morbid curiosities—they were research into what humans actually are beneath the social veneer.

Distortion as Truth: Why Perfect Symmetry Is a Lie

Consider what your face does when you’re in genuine pain or experiencing true ecstasy. It doesn’t stay symmetrical. It twists, contorts, and blurs. Bacon painted the blur. He understood that emotional truth requires visual distortion.

This principle directly challenges the techniques taught in traditional painting styles and art movements. While Impressionists captured the visual blur of light and movement, Bacon captured the psychological blur of intense feeling.

The Power of Visceral Color

Bacon’s color palette wasn’t pretty. He used flesh tones that looked bruised, backgrounds that felt claustrophobic, and contrasts that hurt the eye. This wasn’t accidental—it was strategic. His colors create physical discomfort in viewers, forcing an embodied response rather than intellectual appreciation.

For artists working with oil versus acrylic versus watercolor mediums, Bacon’s preference for oil paints is significant. Oil’s slow drying time allowed him to smear, blend, and manipulate the paint in ways that mimicked flesh, creating his signature visceral quality.

Francis Bacon’s Technical Methods and Materials

Working from Photographs and Memory

Bacon rarely worked from live models. Instead, he collected photographs—some his own, many from books and magazines. He particularly loved images that showed movement blur, faces caught mid-expression, or bodies in awkward positions. These imperfect source materials gave him permission to distort further.

This approach influenced how modern artists work with reference material, especially in our current era where everyone has thousands of reference photos on their phones. Bacon teaches us that the perfect, posed photograph isn’t always the most truthful starting point.

The Role of Chance and “Accident”

Bacon embraced what he called “accidents”—moments when paint behaved unexpectedly, creating effects he couldn’t have planned. He would throw paint at the canvas, use rags to smear it, or apply it with his hands. But these weren’t random actions; they were controlled chaos, strategic risks taken within a framework of intentional composition.

This balance between control and chance relates to fundamental painting principles but pushes them to extremes. Bacon maintained compositional structure while allowing surface details to emerge organically.

How to Apply Francis Bacon’s Lessons to Your Own Work

Choosing the Right Medium for Bacon-Inspired Techniques

While Bacon used oils, contemporary artists can achieve similar effects with heavy-body acrylics. Personally, I treat acrylics as a sculptural medium. The fast drying time matches my frantic thought process, and I can build a face up through layers rather than washing it out like watercolor.

I hate the passivity of watercolor—letting water dictate the flow of pigment feels like a lack of discipline. With acrylics, I control the violence on the canvas. I can pile paint on until it looks like bruised flesh, creating the visceral quality Bacon achieved with oils.

Practical Exercises to Develop Bacon-Style Distortion

Exercise 1: Paint from Blurred Photos Take portrait reference photos and intentionally blur them before painting. This forces you to focus on overall form and color masses rather than precise details.

Exercise 2: The Multiple-Angle Face Inspired by Cubism’s multiple perspectives, paint a single face from three different angles simultaneously on the same canvas. Let the overlapping views create natural distortions.

Exercise 3: Emotion-Based Elongation Pick an emotion—tension, ecstasy, fear. Elongate or compress facial features based on how that emotion feels physically. Necks can stretch like Modigliani to show tension. Foreheads can fracture like Picasso to show a headache.

Creating Depth Through Layering, Not Blending

Bacon’s paintings have remarkable physical depth created through layering rather than smooth blending. Apply paint in distinct layers, letting some dry completely before adding more. This creates a sense of archaeological depth—you’re not just painting a face, you’re excavating one.

This layering approach works particularly well when painting backgrounds. Bacon often used flat, geometric backgrounds that made his distorted figures pop forward, creating uncomfortable spatial tension.

The Rebellion of Flaws: Why Imperfection Is Powerful

How AI Art Proves Bacon’s Point

In a market obsessed with “content” and “aesthetic,” painting ugly is an act of rebellion. AI can replicate a da Vinci style. It can churn out a “perfect” girl with a pearl earring in three seconds. But it cannot replicate the feeling of a Francis Bacon painting because AI has never felt nausea. It has never felt dread. It has never felt the desire to tear its own skin off.

This distinction becomes crucial when understanding technology’s impact on contemporary portraiture. While digital tools can enhance traditional techniques, they can’t replace the embodied experience that creates truly powerful work.

Embracing Asymmetry and Visual Discomfort

When I paint a portrait now, I actively search for asymmetry. I elongate the neck to show tension. I fracture the forehead to show mental pressure. I use jagged, aggressive strokes because life is jagged and aggressive. These “flaws” carry more truth than any perfectly rendered face ever could.

| Traditional Portrait Approach | Bacon-Inspired Approach |

|---|---|

| Symmetrical features | Strategic asymmetry |

| Smooth blending | Visible brushstrokes |

| Flattering angles | Psychologically revealing angles |

| Pretty color palettes | Visceral, uncomfortable colors |

| Subject at rest | Subject in psychological motion |

| Technical perfection | Emotional truth |

Learning from Other Expressive Artists

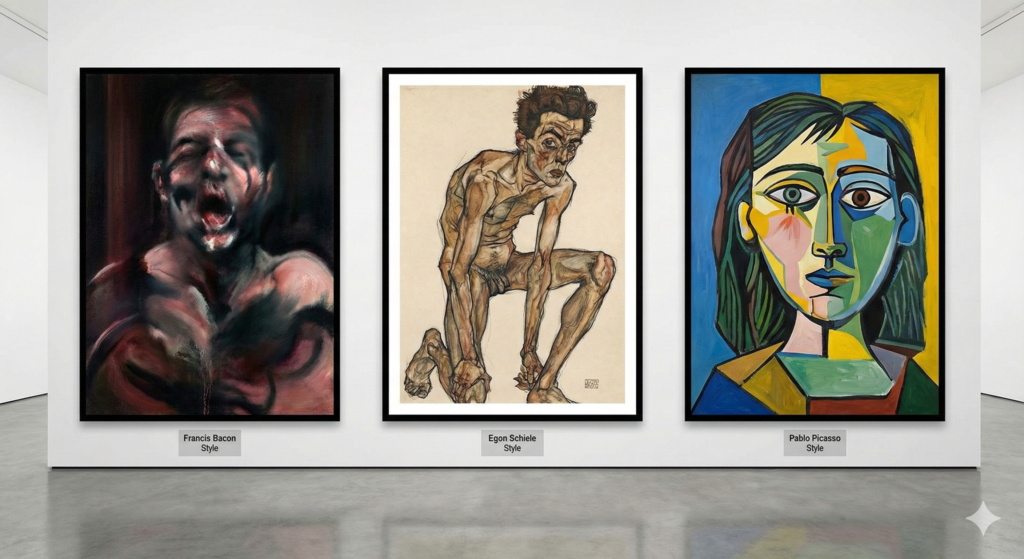

Bacon didn’t work in isolation. He was influenced by and conversed with other artists who rejected prettiness:

- Egon Schiele: Angular, sexually charged figures with exaggerated gestures

- Amedeo Modigliani: Elongated forms that emphasized psychological states

- Pablo Picasso: Cubist fragmentation of the human figure

- Lucian Freud: Unflinching realism that emphasized flesh as meat

Understanding these connections helps us see Bacon within the larger context of famous painters and paintings that challenged conventional beauty.

Common Mistakes When Attempting Bacon-Inspired Work

Over-Distorting Without Purpose

Distortion for its own sake creates cartoon characters, not powerful portraits. Each distortion in Bacon’s work serves an emotional or psychological purpose. Before elongating that neck or fracturing that face, ask yourself: What feeling am I trying to convey?

Neglecting Compositional Structure

Bacon’s paintings work because underneath the surface chaos is rock-solid composition. He used geometric shapes, carefully planned spatial relationships, and strong value contrasts. The fundamental principles of painting still apply—you’re just using them to different ends.

Forgetting the Original Subject

Even at his most abstract, Bacon never completely abandoned the figure. His distortions remain recognizably human. Push too far and you lose the tension between representation and abstraction that makes this work powerful.

Francis Bacon’s Legacy in Contemporary Art

Modern Artists Influenced by Bacon

Bacon’s influence extends far beyond his death in 1992. Contemporary artists continue to reference his visceral approach:

- Jenny Saville: Creates massive portraits of flesh that challenge beauty standards

- Cecily Brown: Combines figuration and abstraction with Bacon-like energy

- George Condo: Uses “artificial realism” to create psychologically charged portraits

- Adrian Ghenie: Distorts historical and contemporary figures using Bacon-inspired techniques

Why Bacon Matters More Than Ever

In our current moment of AI-generated perfection and Instagram filters, Bacon’s insistence on the uncomfortable, the imperfect, and the viscerally human becomes more relevant, not less. His work reminds us that art’s job isn’t to make things pretty—it’s to make us feel.

This perspective directly challenges the commodification of art we see in discussions about the most profitable painting styles. While certain styles sell better, Bacon reminds us that commercial success and artistic truth don’t always align.

Resources for Studying Francis Bacon Further

Essential Books

- “Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma” by Michael Peppiatt – The definitive biography providing insight into Bacon’s life, methods, and philosophy

- “Francis Bacon: Catalogue Raisonné” edited by Martin Harrison – Complete catalog of Bacon’s paintings with detailed analysis

- “The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon” by David Sylvester – Direct conversations revealing Bacon’s thought process

Museums with Major Bacon Collections

- Tate Britain, London – Holds the largest collection of Bacon’s work

- Museum of Modern Art, New York – Features key works from different periods

- Centre Pompidou, Paris – Houses important Bacon paintings and studies

- Guggenheim Museum, New York – Includes significant later works

Online Resources

For those interested in exploring Bacon’s techniques in depth, the Tate’s Francis Bacon resource provides extensive analysis and high-resolution images of his work. The Francis Bacon MB Art Foundation offers virtual exhibitions and scholarly articles examining his influence on contemporary art.

Final Thoughts: Put Down the Blending Brush

My advice to young painters is simple: Stop smoothing everything out. Leave the brushstrokes visible. Let the colors clash. If the nose looks broken, ask yourself – does it feel right emotionally? If the answer is yes, leave it alone.

Don’t paint the face they show the camera. Paint the face they wear when they think no one is watching. That’s where the beauty is. It’s messy, it’s uncomfortable, and it’s the only thing the machines can’t take from us. Francis Bacon understood this truth decades before AI ever existed. He knew that perfection is the enemy of feeling, that symmetry is often a lie, and that the most powerful portraits show us not what people look like, but what it feels like to be human. When you pick up your brush – whether it’s loaded with oil, acrylic, or whatever medium calls to you – remember that your job isn’t to make something pretty. It’s to make something true. And truth, as Bacon showed us again and again, is rarely pretty. It’s raw, visceral, uncomfortable, and absolutely essential.

Frequently Asked Questions

What made Francis Bacon’s painting style so unique?

Francis Bacon’s painting style was unique because he focused on psychological and emotional truth rather than physical beauty. He used distortion, blurred features, and visceral colors to capture the human condition in its rawest form, rejecting traditional portrait conventions in favor of expressing inner states of being.

Did Francis Bacon have formal art training?

No, Francis Bacon was largely self-taught. He never received formal art education, which may have contributed to his willingness to break conventional rules. He learned by studying art books, visiting museums, and experimenting with techniques on his own terms.

What painting medium did Francis Bacon prefer?

Francis Bacon primarily worked with oil paints. He appreciated their slow drying time, which allowed him to manipulate, smear, and blend the paint to create his signature flesh-like textures and distorted forms. However, contemporary artists can achieve similar effects with heavy-body acrylics.

How can beginners start painting in a Bacon-inspired style?

Beginners should start by working from blurred photographs rather than perfectly clear references. Practice distorting features based on emotion rather than anatomy, leave brushstrokes visible instead of over-blending, and focus on creating psychological impact rather than technical perfection. Understanding basic composition and painting techniques provides a foundation for intentional distortion.

Why did Francis Bacon paint screaming figures so often?

Bacon was fascinated by human vulnerability, suffering, and the breakdown of social masks. The scream represented a moment of absolute emotional truth when all pretense strips away. He was particularly influenced by the Eisenstein film “Battleship Potemkin,” especially the famous screaming nurse scene.

Is Francis Bacon’s work considered Expressionism?

While Bacon’s work shares emotional intensity with Expressionism, he rejected the label. His approach was more about “recording” psychological reality than expressively interpreting it. He exists somewhat outside traditional art movement categories, though his work relates to both Expressionism and other modern art movements.

What subjects did Francis Bacon paint besides portraits?

Though best known for his portraits and figure studies, Bacon also painted crucifixions, popes (inspired by Velázquez), and occasionally landscapes. However, the human figure remained his primary obsession throughout his career, as he believed it provided the deepest avenue for expressing human experience.

How has Francis Bacon influenced contemporary art?

Bacon’s influence on contemporary art is profound, affecting how artists approach the human figure, emotional authenticity, and the rejection of idealized beauty. His work paved the way for artists who prioritize psychological truth over technical perfection and continues to inspire those resisting AI-generated “perfect” art.