When you think about Romantic art and literature, you might picture beautiful paintings of mountains, forests, and lakes. But nature meant something far more profound to Romantic artists and writers than just a pretty backdrop. For them, nature was a powerful spiritual force, a source of terror and awe, and a refuge from an increasingly industrialized world. This movement, which flourished from the late 1700s to the mid-1800s, completely transformed how people viewed the natural world—and its influence still echoes in how we think about nature today.

Key Points:

- Romanticism emerged as a reaction against Enlightenment rationalism and industrialization

- Nature represented spiritual truth, emotional depth, and sublime power—not just beauty

- The “sublime” described nature’s overwhelming, even terrifying aspects

- Romantic artists and writers saw nature as a teacher, healer, and divine force

- This movement laid the groundwork for modern environmental consciousness

What Was Romanticism Really About?

Romanticism wasn’t just an art style—it was a revolutionary way of thinking. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Enlightenment had championed reason, science, and logic above all else. Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution was transforming Europe, bringing factories, urbanization, and pollution. Romantic thinkers pushed back against both trends.

They believed that emotion, imagination, and intuition were just as important—if not more important—than cold logic. They celebrated individualism and subjective experience over universal rules. And they saw nature not as something to be measured, catalogued, and conquered, but as a living force that could teach humanity profound truths.

The Sublime: When Nature Inspires Awe and Terror

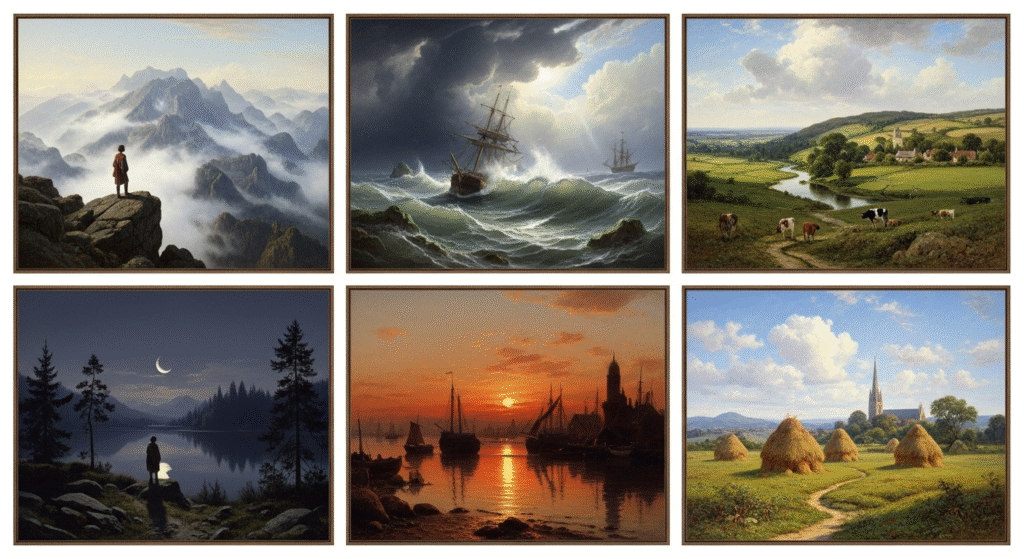

One of the most important concepts in Romanticism was the “sublime.” This wasn’t about beauty in the traditional sense. The sublime described experiences that were overwhelming, even frightening—vast mountain ranges, raging storms, endless oceans, or towering waterfalls.

Philosophers like Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant explored this idea in depth. Burke argued that the sublime combined pleasure with pain—the thrill of experiencing nature’s raw power while knowing you could be destroyed by it. Kant saw it as nature’s ability to make us feel simultaneously insignificant and elevated, challenging our minds to grasp the incomprehensible.

The Beautiful vs. The Sublime

| The Beautiful | The Sublime |

|---|---|

| Orderly and harmonious | Wild and chaotic |

| Calming and pleasant | Overwhelming and intense |

| Human-scaled | Vast and incomprehensible |

| Predictable | Unpredictable and dangerous |

| Invites contemplation | Inspires awe and terror |

German painter Caspar David Friedrich became famous for capturing the sublime in his work. His masterpiece “Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” (1818) shows a lone figure standing on a rocky peak, gazing out over an endless sea of mist and mountains. The painting doesn’t just show a pretty view—it makes you feel the vastness of nature and the small place humans occupy within it.

Similarly, British artist J.M.W. Turner painted dramatic seascapes where ships struggled against massive waves and violent storms. His paintings like “The Slave Ship” (1840) showed nature’s terrible power, reminding viewers that the natural world couldn’t be tamed or controlled.

Nature as Spiritual Teacher and Divine Language

For Romantic thinkers, nature wasn’t just matter obeying physical laws—it was alive with spiritual meaning. They rejected the Enlightenment view that nature was simply “dead matter” to be dissected by science. Instead, they saw the natural world as a kind of divine language, full of symbols and messages from a higher power.

English poet William Wordsworth famously wrote about nature as his greatest teacher. In his poem “The Tables Turned,” he encouraged readers to:

“Come forth into the light of things, Let Nature be your teacher.”

Wordsworth believed that spending time in nature could teach people more about truth, morality, and beauty than any book. His autobiographical poem “The Prelude” describes how encounters with mountains and lakes shaped his entire philosophy and spiritual development.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which came slightly later, continued this tradition of finding spiritual meaning in natural details, though their approach differed from earlier Romantics.

Nature as Refuge from Industrial Society

As cities grew larger and factories multiplied, many Romantic artists and writers fled to the countryside. They saw urban life as alienating, artificial, and destructive to the human spirit. Nature became a refuge—a place to escape and rediscover authentic emotions and experiences.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote about this in poems like “Frost at Midnight,” where he contrasts the cramped, smoky city with the open beauty of the countryside. He hopes his son will grow up surrounded by nature rather than “close at the bars of a gaoler’s house.”

This wasn’t just nostalgia for a simpler past. Romantics genuinely believed that industrial society was making people sick—both physically and spiritually. They saw nature as a healer, offering fresh air, beauty, and a sense of connection that the modern world destroyed.

John Constable, an English landscape painter, dedicated his career to capturing the beauty of the English countryside before it disappeared. His paintings of Suffolk farmland, like “The Hay Wain” (1821), celebrated rural life and natural scenery with loving detail.

The Romantic Self: Alone with Nature

Romanticism placed enormous emphasis on individual experience and personal emotion. Many Romantic artworks feature solitary figures alone in vast landscapes—think of Friedrich’s wanderer, standing by himself on that mountaintop.

These lone figures weren’t just admiring the view. They were engaging in deep contemplation about their place in the universe, their own emotions, and the meaning of existence. Nature served as a mirror for their inner feelings—stormy weather reflected inner turmoil, while calm lakes suggested peace.

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “Mont Blanc” describes climbing in the Alps and being overwhelmed by the mountain’s power. But the poem isn’t really about the mountain—it’s about Shelley’s mind grappling with huge philosophical questions about power, mortality, and human consciousness.

This emphasis on subjective experience was revolutionary. Instead of trying to describe nature “objectively,” Romantic artists and writers openly explored how nature made them feel. Your emotional response to nature was just as valid and important as anyone else’s.

Seeds of Environmentalism: Romanticism’s Lasting Impact

Though Romantics didn’t use the word “environmentalism,” they planted many ideas that would grow into the modern conservation movement. By celebrating wild nature and critiquing industrialization’s destructive effects, they challenged the assumption that “progress” always meant dominating and exploiting the natural world.

Writers like Lord Byron wrote scathing critiques of deforestation and pollution. Mary Shelley’s novel “Frankenstein” (1818) warned about the dangers of science without wisdom or respect for nature. These weren’t just literary themes—they were urgent social critiques.

The Romantic movement influenced later conservation pioneers like John Muir and Henry David Thoreau, who explicitly cited Romantic poets as inspiration for their environmental activism. When we set aside national parks, oppose pollution, or fight climate change today, we’re continuing conversations that Romantics started two centuries ago.

The Hudson River School in America adopted many Romantic ideals, celebrating the American wilderness as a source of national identity and spiritual renewal.

Key Artists and Writers Who Shaped Romantic Nature

In Literature:

- William Wordsworth – Celebrated nature as spiritual teacher and source of moral wisdom

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge – Explored imagination’s role in perceiving nature’s deeper meanings

- Percy Bysshe Shelley – Wrote about nature’s sublime power and radical political potential

- John Keats – Found beauty and truth through intense sensory experiences of nature

- Lord Byron – Created brooding heroes who sought meaning in wild landscapes

In Art:

- Caspar David Friedrich – Master of sublime landscapes with contemplative figures

- J.M.W. Turner – Captured nature’s dynamic power through light and color

- John Constable – Depicted English countryside with scientific observation and deep affection

- Eugène Delacroix – Brought dramatic emotion to both nature and historical scenes

Why This Still Matters Today

Understanding how Romanticism transformed humanity’s relationship with nature helps us make sense of our own complicated feelings about the natural world. When you feel awed by a sunset, refreshed by a hike, or worried about climate change, you’re experiencing echoes of Romantic ideas.

The Romantic movement reminds us that nature isn’t just resources to exploit or scenery to photograph—it’s a complex, powerful force that shapes who we are. In an age of screens, cities, and climate crisis, the Romantic insistence on nature’s importance feels more relevant than ever. By looking beyond pretty landscapes to nature’s deeper meanings, the Romantics gave us tools for thinking about our place in the world—tools we still desperately need today.

Frequently Asked Questions

What role did nature play in Romanticism?

Nature was central to Romanticism, serving as a spiritual teacher, source of sublime experiences, refuge from industrialization, and mirror for human emotions. Romantics viewed nature as a living, divine force rather than dead matter to be analyzed scientifically.

How did Romanticism differ from the Enlightenment period in its view of nature?

The Enlightenment emphasized rational, scientific understanding of nature as something to be measured, catalogued, and controlled. Romanticism rejected this approach, instead celebrating emotion, intuition, and spiritual connection with nature. Romantics valued subjective experience over objective analysis.

Why was emotion such an important aspect of Romantic works connected to nature?

Romantics believed emotion and imagination provided access to deeper truths than reason alone. They saw authentic emotional responses to nature—awe, terror, joy, melancholy—as valid ways of understanding reality and connecting with the divine or spiritual aspects of existence.

Does Romanticism go beyond nature appreciation and admiration?

Absolutely. While Romantics appreciated nature’s beauty, they saw it as a powerful spiritual force, a teacher of moral truths, a critique of industrial society, and a source of sublime terror. Nature represented freedom, authenticity, and connection to something greater than human civilization.

What is the sublime in Romanticism?

The sublime describes overwhelming experiences of nature’s vast power—massive mountains, violent storms, endless oceans. Unlike simple beauty, the sublime combines pleasure with terror, making observers feel both insignificant and elevated. Philosophers like Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant developed this concept extensively.

Additional Resources

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Romanticism – Comprehensive overview of Romantic art movement

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Romanticism – Philosophical foundations of Romantic thought

- The National Gallery – Constable and Turner – Major collection of Romantic landscape paintings

- Poetry Foundation – Romantic Poets – Complete works of Wordsworth, Coleridge, and other Romantic poets

- Khan Academy – Romanticism Overview – Educational resources on Romantic art and culture

- The Caspar David Friedrich Society – Dedicated resource for Friedrich’s work and influence