Have you ever looked at a painting and felt like it was telling you the story of real people’s struggles, hopes, and everyday battles? That’s the power of Social Realism art —a movement that transformed painting from pretty pictures into powerful social commentary. Unlike art that just shows beautiful scenes or abstract shapes, Social Realism uses technical mastery and honest storytelling to shine a spotlight on working people, social injustices, and the raw truth of human experience. Born during times of economic hardship and political upheaval in the early 20th century, this art movement proved that a well-executed brushstroke could be just as powerful as a protest sign.

Key Points Summary

- Social Realism emerged in the early 1900s as artists responded to industrialization, economic crises, and social inequality

- Core techniques include precise value control, truthful depiction, and compositional strategies that guide viewers toward the social message

- Famous practitioners like Diego Rivera, Dorothea Lange, and Jacob Lawrence developed distinctive approaches to convey working-class experiences

- Social Realism differs from Socialist Realism—it’s critical social commentary, not government propaganda

- The movement’s legacy continues today in contemporary art addressing social justice issues

Understanding Social Realism: Art with a Purpose

Social Realism isn’t just another art style—it’s art with a mission. While realism in art aims to show the world accurately, Social Realism takes it further by focusing specifically on social and political issues affecting ordinary people.

What Makes Social Realism Different?

Think of Social Realism as journalism meets fine art. These artists weren’t interested in painting fancy portraits of rich people or dreamy landscapes. Instead, they wanted to document and expose:

- The harsh realities of working-class life

- Economic inequality and poverty

- Labor struggles and workers’ rights

- The effects of industrialization on communities

- Racial and social injustices

The movement gained momentum during the Great Depression of the 1930s when millions of people lost their jobs, homes, and hope. Artists felt compelled to show what was really happening in society—not the glossy, idealized version but the gritty truth.

Social Realism vs. Socialist Realism: A Critical Distinction

Here’s where things get confusing for many people. Social Realism and Socialist Realism sound similar but are actually quite different:

| Social Realism | Socialist Realism |

|---|---|

| Independent artistic expression | State-mandated propaganda |

| Critical of social problems | Idealized depictions of society |

| Diverse artistic styles | Strict, prescribed aesthetic |

| Shows struggle and hardship | Shows heroic workers and perfect society |

| Found globally (USA, Mexico, Europe) | Specific to Soviet Union and Communist states |

Social Realism artists could criticize their governments and expose problems. Socialist Realism artists had to follow government rules and make everything look perfect and inspirational. One questions society; the other promotes it.

The Core Characteristics That Define Social Realism

Truthful and Unembellished Depiction

Social Realist artists rejected the romantic, prettified approach of earlier art movements. No soft-focus lenses here! They painted:

- Weathered faces with lines earned from hard work

- Worn, patched clothing instead of fancy fabrics

- Real factories, mines, and tenements—not idealized settings

- Genuine emotions: exhaustion, determination, dignity, struggle

As photographer and Social Realist Dorothea Lange famously said:

“The camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.”

This philosophy applied to all Social Realist mediums—show people what they’re missing or ignoring.

Focus on the Human Condition

Every Social Realism artwork centers on human experience, particularly of marginalized groups:

- Factory workers and miners

- Migrant laborers and farmers

- Urban poor and unemployed

- Racial minorities facing discrimination

- Women in difficult circumstances

The goal? To make viewers see these people as individuals with dignity, not just statistics or invisible members of society.

Narrative Storytelling Through Visual Art

Social Realist works tell stories you can follow. They’re like freeze-frames from a movie about real life. Artists carefully composed scenes to create narratives that viewers could understand immediately—no art history degree required.

Essential Social Realism Techniques: The Technical Foundation

Now let’s get into the actual brushwork and methods that made Social Realism so powerful. These aren’t just random techniques—each serves the movement’s goal of honest, impactful communication.

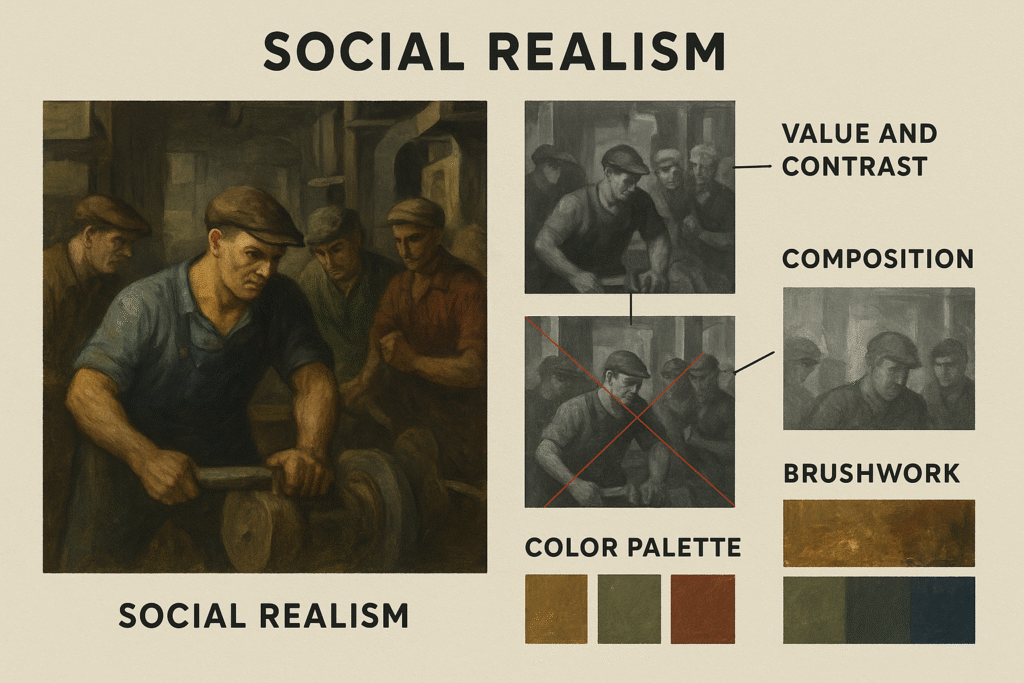

Mastering Value and Contrast

Value (the lightness or darkness of colors) is absolutely crucial in Social Realism. Artists used dramatic contrasts between light and dark to:

- Create three-dimensional forms that feel solid and real

- Draw attention to important subjects

- Add emotional weight and drama

- Emphasize the harshness of lighting in industrial settings

Think about a coal miner emerging from darkness into light—that value shift tells a story about moving from underground hardship to brief relief.

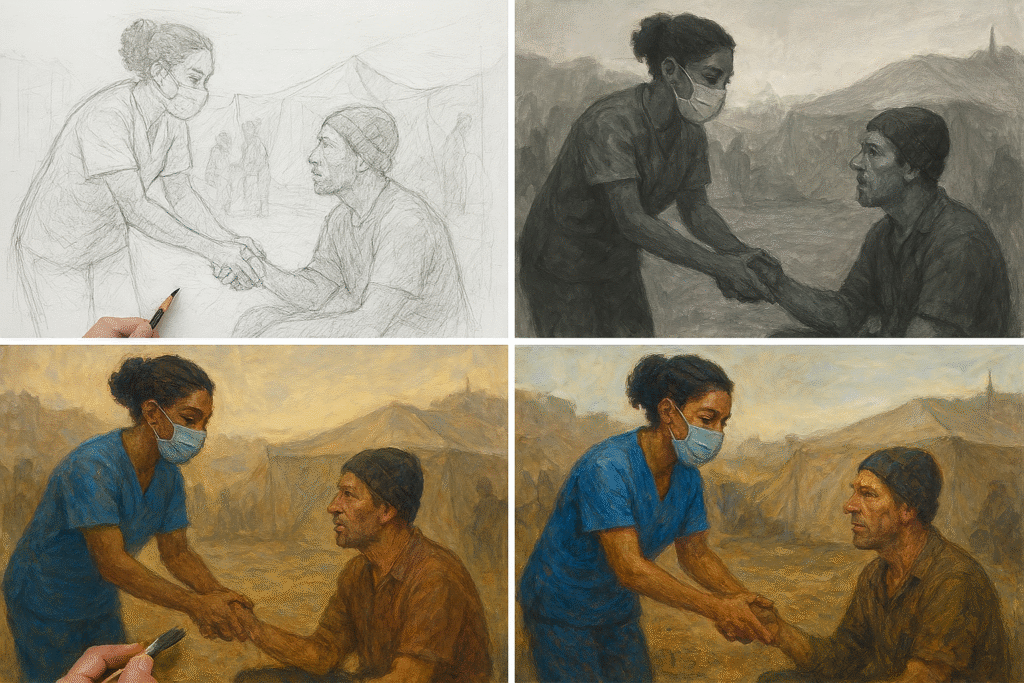

Precision in Drawing and Observation

Drawing techniques form the foundation of Social Realism. Artists spent countless hours:

- Sketching from life to capture authentic poses and expressions

- Studying anatomy to render bodies accurately under strain or labor

- Observing how fabrics drape, wrinkle, and wear

- Recording exact architectural details of tenements and factories

This precision wasn’t about showing off technical skill—it was about credibility. Viewers had to believe these scenes were real.

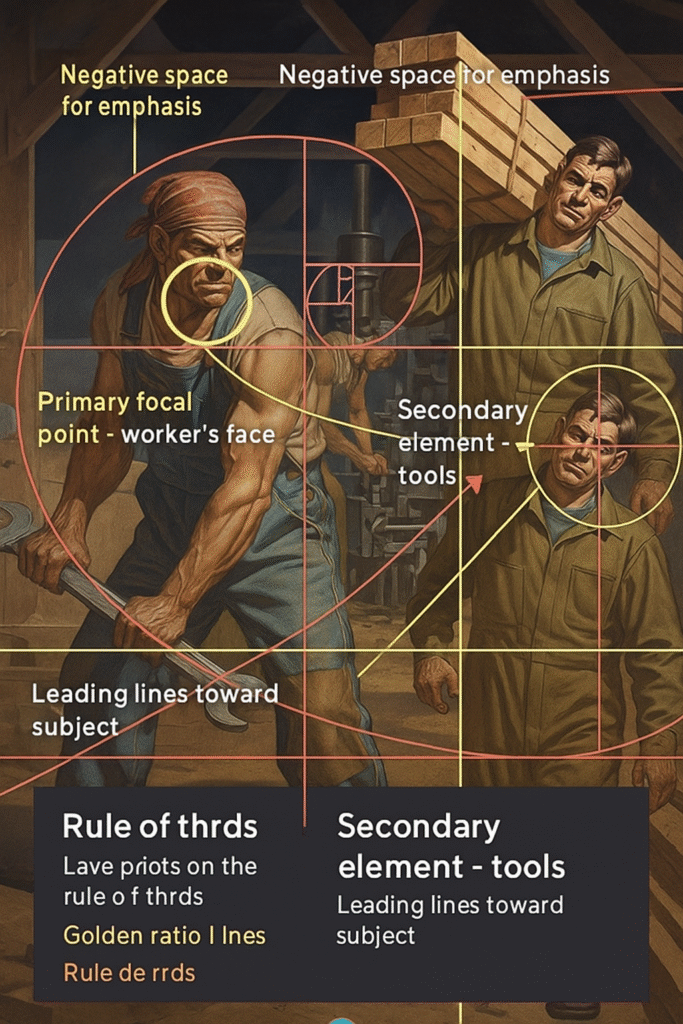

Composition for Social Impact

Social Realist composition strategies include:

Monumental Storytelling: Even ordinary people were painted on heroic scales, giving dignity and importance to working-class subjects. Mexican muralist Diego Rivera excelled at this—his factory workers tower over viewers, impossible to ignore.

Strategic Placement: Important figures or symbols positioned where the eye naturally travels (following the rule of thirds or creating strong diagonals).

Environmental Context: Including enough setting details to establish the social situation without cluttering the message.

Eye Level Choices: Placing viewers at eye level with subjects (equality) or sometimes looking up at workers (respect, monumentality).

Creating Perspective and Believable Space

Social Realist scenes needed convincing spatial depth because the narratives unfolded in specific places—real factories, real streets, real homes. Artists used:

- Linear perspective to create deep factory floors or crowded urban streets

- Atmospheric perspective for outdoor scenes

- Overlapping figures to show crowded living conditions

- Scale relationships to emphasize cramped spaces or vast industrial complexes

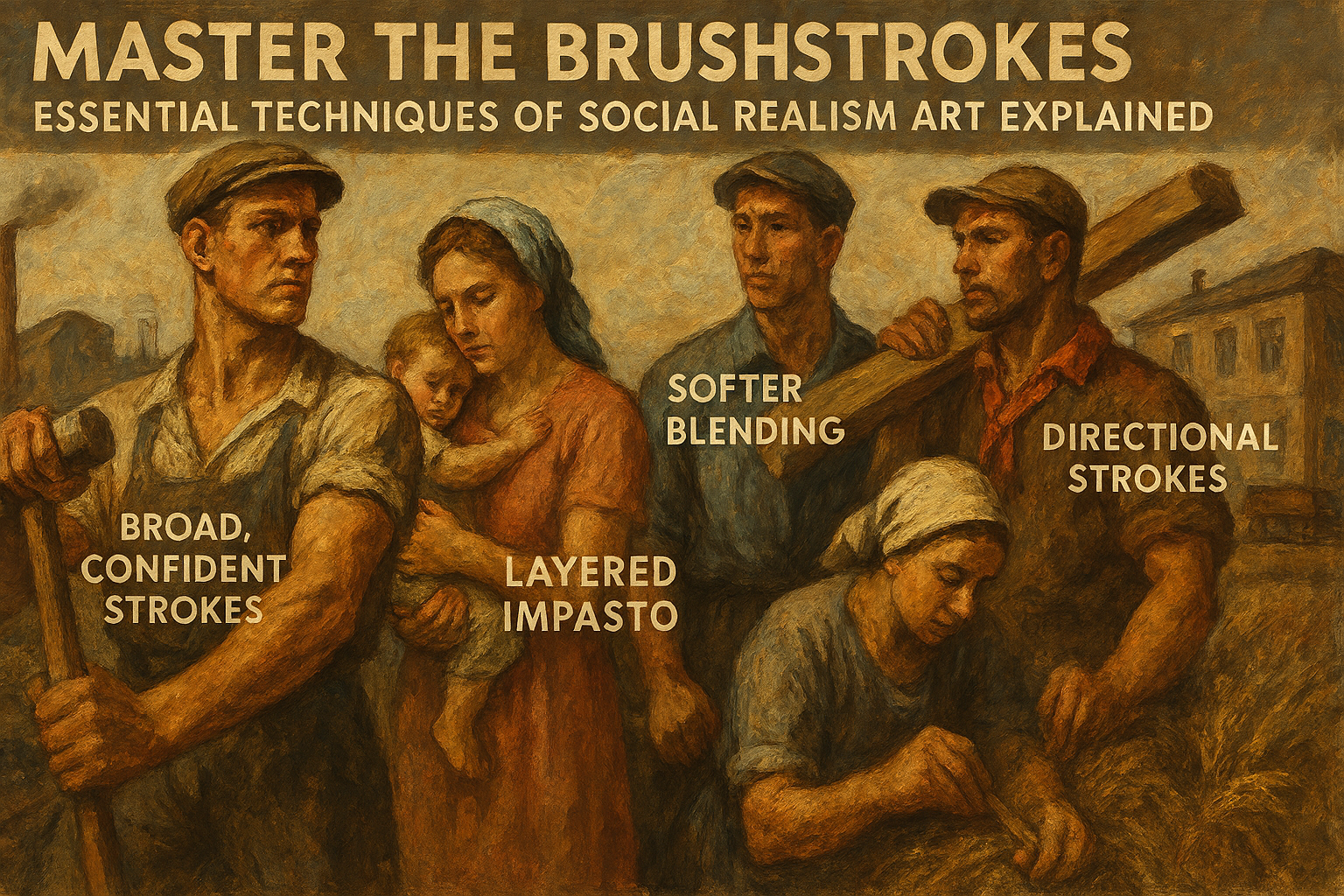

Brushwork Techniques: From Descriptive to Expressive

The actual way Social Realist artists applied paint varied, but always served the social message.

Descriptive Brushwork: The Naturalistic Approach

Some Social Realists used incredibly smooth, almost invisible brushstrokes to create photographic realism. This technique:

- Makes viewers focus on the subject, not the technique

- Emphasizes documentary-style truthfulness

- Works well for portraits where every facial detail matters

- Creates an “objective” feeling—like a neutral witness

Ben Shahn often used this approach in his paintings documenting labor disputes and social injustice.

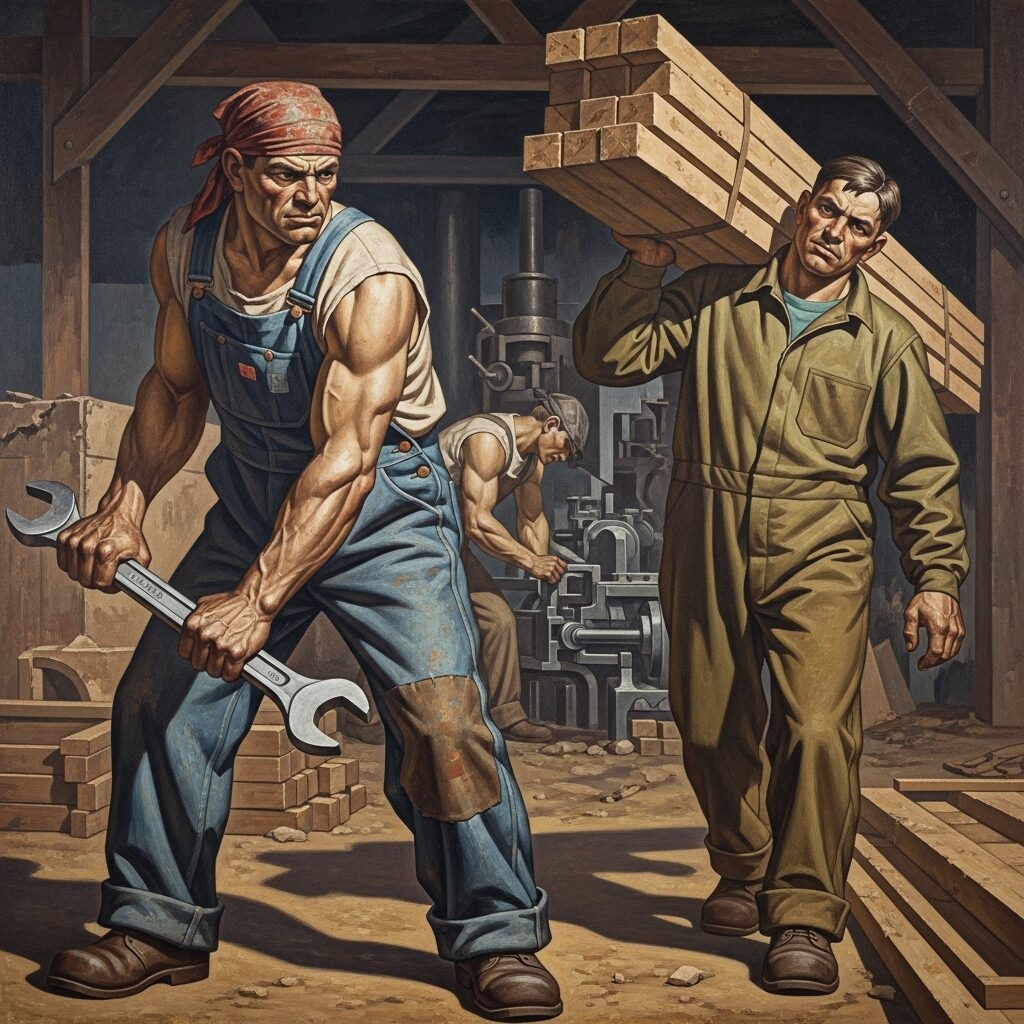

Expressive Brushwork: Adding Emotional Intensity

Other artists used more visible, energetic strokes to convey emotion and urgency. Think of:

- Quick, gestural marks suggesting movement and activity

- Rough textures communicating harsh living conditions

- Bold, confident strokes that feel passionate rather than clinical

- Directional brushwork guiding the eye and creating rhythm

This approach adds artistic interpretation while maintaining realistic representation.

Depicting Texture and Grit

One hallmark of Social Realism is how artists rendered the unglamorous textures of working life:

For worn fabrics: Short, broken strokes following the fabric’s weave, varied values showing threadbare areas

For weathered skin: Careful modeling with warm and cool tones, precise value shifts showing wrinkles and sun damage

For industrial surfaces: Thick paint application mimicking rust, dirt, and wear; sometimes using palette knives for metallic textures

For architectural decay: Rough, broken brushwork suggesting crumbling plaster, peeling paint, and neglect

Conveying Emotion Through Technique

Brushwork contributed directly to emotional content:

- Tension: Rigid, controlled strokes for figures under stress

- Exhaustion: Loose, sagging lines in body postures

- Determination: Strong, directional marks in heroic worker compositions

- Despair: Muted, heavy application with little variation

Facial expressions received particular attention. Painting realistic faces required subtle value transitions and careful observation of how muscles move under emotional states.

Color Palette Choices in Social Realism

Social Realist color theory often emphasized certain palettes to reinforce themes:

Muted and Somber Tones

Many Social Realist works used restricted palettes featuring:

- Earth tones (browns, ochres, siennas)

- Grays and near-grays

- Desaturated blues and greens

- Limited bright colors

This reflected the grim reality of poverty and hardship while creating visual unity. The muted palette also prevented decorative prettiness from undermining serious content.

Bold Colors for Impact

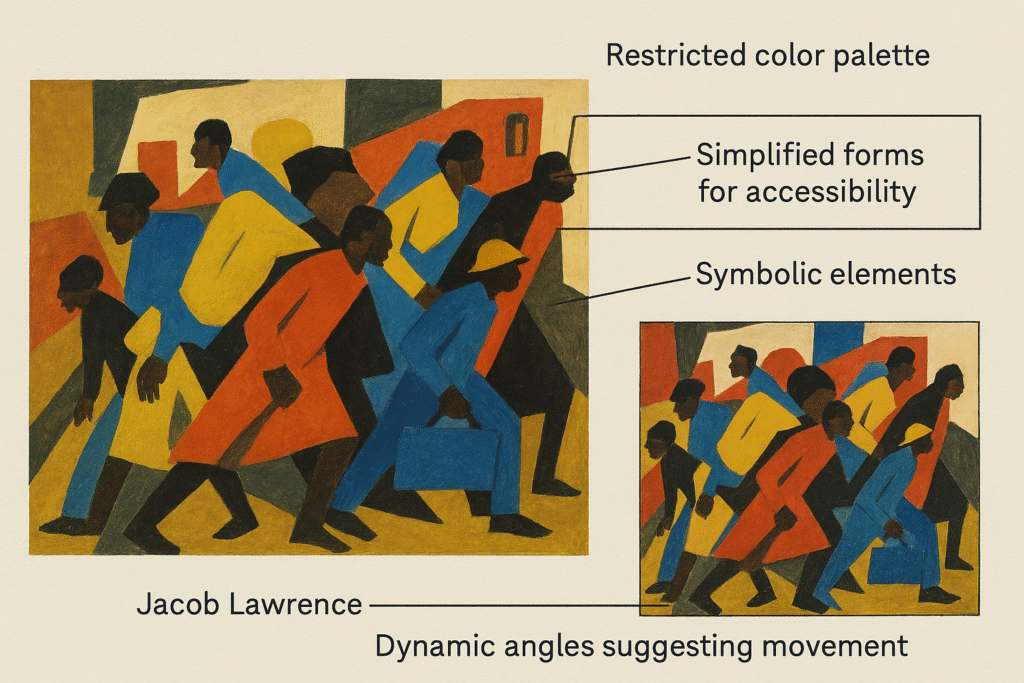

Not all Social Realism was drab! Jacob Lawrence used vibrant, bold colors in his Migration Series, proving that strong hues could enhance rather than detract from social commentary. His approach:

- Created visual accessibility and engagement

- Honored African American culture and experience

- Used color symbolically (reds for danger or passion, blues for hope or sorrow)

- Made complex narratives easier to follow through color coding

The key was intentionality—every color choice served the message.

Simplification and Symbolism

While maintaining realistic representation, many Social Realists simplified forms for clarity and impact:

- Flattened depth in some areas to create poster-like directness

- Reduced detail in backgrounds to emphasize subjects

- Symbolic objects (tools, machinery, chains, bread) as visual shorthand

- Archetypal figures representing groups rather than specific individuals

This made the art more accessible to diverse audiences, including those with limited art education. A factory worker could immediately understand the symbolism without needing to decode complex artistic references.

Mediums and Materials: Tools of Social Commentary

Mural Painting and Fresco

Murals became the ultimate Social Realist medium because they were:

- Public and free—anyone could see them

- Monumental—impossible to ignore

- Permanent—lasting statements in community spaces

- Educational—telling stories to illiterate audiences

Diego Rivera pioneered the modern fresco painting technique for Social Realist murals. Working with wet plaster required planning every detail in advance, but the results were incredibly durable and vivid.

His Detroit Industry Murals (1932-33) show the entire industrial process from mining raw materials to assembling automobiles, celebrating workers while also hinting at the dehumanizing aspects of factory labor.

Oil and Tempera Painting

Traditional easel painting remained important for:

- Detailed, careful observations

- Portable works that could travel to exhibitions

- More intimate, personal statements

- Complex color and surface effects

Frida Kahlo used oil paint for her deeply personal yet socially critical self-portraits, addressing gender, identity, Mexican culture, and physical suffering.

Printmaking: Democratizing Art

Woodcuts, lithographs, and etchings allowed Social Realists to:

- Produce multiple affordable copies

- Distribute art to working-class audiences

- Create high-contrast, graphic images perfect for social messaging

- Illustrate books, pamphlets, and political publications

The bold, simplified forms of printmaking naturally aligned with Social Realism’s accessible aesthetic.

Photography: Capturing Reality Directly

Photography became a powerful Social Realist tool, offering:

- Undeniable documentary evidence

- Speed—capturing decisive moments

- Apparent objectivity

- Wide distribution through newspapers and magazines

Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” (1936) remains perhaps the most iconic Social Realist image ever created, showing a desperate mother and her children during the Depression with raw, heartbreaking honesty.

Learning from the Masters: Famous Social Realist Artists

Let’s examine how specific artists embodied Social Realism techniques:

Diego Rivera: Monumental Vision

Key Techniques:

- Massive scale elevating workers to heroic status

- Fresco mastery creating luminous, durable surfaces

- Complex compositions with multiple narrative threads

- Mixing Pre-Columbian, Renaissance, and modern influences

- Strong outlines defining forms clearly

Social Focus: Mexican history, indigenous peoples, industrial workers, anti-capitalism, class struggle

Rivera showed that monumental art didn’t belong only to churches and palaces—it could celebrate everyday workers with the same grandeur.

Dorothea Lange: Dignified Documentation

Key Techniques:

- Candid approach—minimal direction of subjects

- Close framing emphasizing faces and expressions

- Available light creating authentic mood

- Careful composition within documentary constraints

- Capturing gesture and body language

Social Focus: Depression-era poverty, migrant farm workers, displaced families, human resilience

Lange’s photography proved that technical excellence and social purpose weren’t contradictory—her images are both artistically sophisticated and deeply humanitarian.

Ben Shahn: Expressive Distortion

Key Techniques:

- Elongated, angular figures creating emotional tension

- Slightly exaggerated proportions emphasizing vulnerability or power

- Flat, poster-like compositions

- Symbolic elements and text integration

- Tempera creating matte, graphic surfaces

Social Focus: Labor rights, political persecution, social injustice, atomic age fears

Shahn demonstrated that Social Realism didn’t require photographic accuracy—expressive distortion could actually strengthen social commentary.

Jacob Lawrence: Narrative Innovation

Key Techniques:

- Sequential storytelling across multiple panels

- Vivid, non-naturalistic color schemes

- Simplified, pattern-based compositions

- Dynamic, angular figures suggesting movement

- Decorative elements from African American culture

Social Focus: African American history, the Great Migration, racial discrimination, community strength

Lawrence’s Migration Series (1940-41) used 60 panels to tell the epic story of African Americans leaving the rural South for Northern cities—a masterpiece of narrative art addressing systemic racism and economic opportunity.

Frida Kahlo: Personal as Political

Key Techniques:

- Intense self-examination through self-portraiture

- Symbolic imagery from Mexican folk art

- Surrealist elements within realistic rendering

- Precise, detailed execution

- Integration of text and image

Social Focus: Gender identity, physical suffering, Mexican national identity, post-colonial culture, female experience

Kahlo proved that deeply personal art could simultaneously address broader social issues—her exploration of female pain and identity resonated far beyond her individual experience.

The Ashcan School: Urban Reality

Predating Social Realism proper, artists like George Luks and Robert Henri established crucial precedents by:

- Painting everyday urban scenes instead of idealized subjects

- Showing working-class neighborhoods honestly

- Using loose, vigorous brushwork

- Finding beauty and dignity in ordinary life

Their willingness to depict gritty urban reality paved the way for the more explicitly political Social Realism that followed.

Practical Techniques You Can Apply Today

Want to incorporate Social Realist approaches into your own work? Here’s how:

Start with Strong Value Studies

Before touching color, create value sketches:

- Use only black, white, and grays

- Establish your light source and stick to it

- Push contrast—darks should be truly dark

- Check values by squinting at your reference

- Ensure the composition works in pure value before adding color

This value painting foundation will make your final work more powerful.

Observe Real People and Places

Social Realism requires authenticity:

- Sketch from life regularly—coffee shops, public transit, parks

- Take reference photos of working environments

- Study how bodies actually move during physical labor

- Notice details: how clothes bunch, how tools are held, how fatigue shows

- Talk to people about their experiences to inform your work

Develop a Purpose-Driven Composition

Before starting, ask yourself:

- What’s my social message?

- Who is my main subject and why do they matter?

- What emotions do I want viewers to feel?

- What details will strengthen my message?

- What can I eliminate because it distracts?

Every compositional decision should support your social commentary.

Choose Your Palette Intentionally

Consider whether your subject calls for:

- Muted, somber tones for hardship, poverty, or oppression

- Bold, vibrant colors for celebration, resilience, or cultural pride

- Limited palette for visual unity and emotional focus

- Symbolic color where specific hues carry meaning

Test your palette on small studies before committing to the full painting.

Balance Detail with Readability

Social Realism walks a line between realistic detail and clear communication:

- Add detail where it matters (faces, hands, significant objects)

- Simplify backgrounds that don’t advance the narrative

- Use edge variation—sharp edges for emphasis, soft edges for less important areas

- Don’t let technique overshadow message

The Legacy and Contemporary Relevance of Social Realism

Social Realism didn’t end with the 1930s-1950s peak. Its influence continues strongly today.

Influence on Later Movements

Social Realism directly influenced:

- Photorealism (1960s-70s): Though often less political, it borrowed the precise observational approach

- Political Pop Art: Artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein adapted Social Realism’s social commentary for consumer culture

- Street Art and Muralism: Contemporary muralists like Banksy continue the tradition of public, politically engaged art

- Documentary Photography: From the Farm Security Administration to today’s photojournalism

Contemporary Social Realist Artists

Modern artists addressing social issues through realistic representation include:

- Kehinde Wiley: Portraying African Americans in traditionally European aristocratic poses, challenging art history’s racism

- Jenny Saville: Exploring female bodies outside conventional beauty standards

- Liu Xiaodong: Documenting displaced communities and social changes in China

- Njideka Akunyili Crosby: Examining Nigerian-American identity and cultural hybridity

These artists prove that Social Realism’s techniques and purpose remain vital for addressing contemporary issues: immigration, climate change, racial justice, economic inequality, and gender rights.

Applying Social Realist Principles Today

Whether you’re creating fine art, illustration, or digital media, Social Realism offers valuable lessons:

- Art can serve purposes beyond decoration—it can educate, advocate, and inspire change

- Technical mastery enhances credibility—viewers take well-executed work more seriously

- Accessibility matters—art that ordinary people can understand reaches wider audiences

- Dignity and empathy are powerful—showing marginalized people as fully human challenges dehumanizing stereotypes

- Specificity creates universality—detailed, honest depictions of particular situations resonate broadly

“Art is not a mirror held up to reality but a hammer with which to shape it.”

Bertolt Brecht

This quote captures Social Realism’s fundamental belief: art should actively participate in social transformation, not just reflect society passively.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Social Realism Art

From Diego Rivera’s towering murals to Dorothea Lange’s haunting photographs, from Ben Shahn’s expressive workers to Jacob Lawrence’s narrative brilliance, Social Realism art demonstrated that technical mastery and social purpose make powerful partners. The essential techniques we’ve explored—precise value control, truthful observation, purposeful composition, intentional brushwork, and accessible symbolism—all served a greater goal: making invisible people visible, giving voice to the voiceless, and challenging viewers to see their society honestly.

Whether you’re an aspiring artist looking to infuse your work with deeper meaning, an art history enthusiast seeking to understand this crucial movement, or someone who believes art can change the world, Social Realism offers timeless lessons. Its techniques remain as relevant today as when artists first picked up their brushes to document the Great Depression or celebrate working people’s dignity. By mastering these brushstrokes and understanding the philosophy behind them, you can create art that matters—art that looks closely at our world and asks us to do better. That’s the true legacy of Social Realism: proving that great technique in service of great purpose creates art that endures.

Frequently Asked Questions About Social Realism Art

What are the main characteristics of Social Realism art?

The main characteristics include truthful, unembellished depiction of everyday life (especially of working-class and marginalized people), focus on social and political themes, narrative storytelling through visual means, precise technical execution, accessible symbolism, and the goal of inspiring social awareness or change rather than purely aesthetic appreciation.

How is Social Realism different from Socialist Realism?

Social Realism is an independent artistic movement that critically examines social problems and portrays struggles honestly, found globally with diverse styles. Socialist Realism was state-mandated propaganda in the Soviet Union and Communist countries, showing idealized depictions of society and heroic workers, with strict aesthetic guidelines that artists had to follow.

What techniques did Social Realist artists use to create realistic depictions?

Social Realist artists used precise observational drawing, mastery of value and contrast to create three-dimensional forms, careful attention to authentic details (worn clothing, weathered faces, industrial settings), purposeful composition guiding viewers’ attention, varied brushwork from smooth descriptive to expressive gestural marks, and intentional color palettes supporting the emotional message.

Who are some of the most famous Social Realism artists and what did they paint?

Famous Social Realist artists include Diego Rivera (monumental murals of Mexican workers and history), Dorothea Lange (photographs documenting Depression-era poverty like “Migrant Mother”), Ben Shahn (paintings addressing labor rights and social justice), Jacob Lawrence (the Migration Series depicting African American experiences), and Frida Kahlo (self-portraits exploring identity, gender, and Mexican culture).

What was the purpose or goal of the Social Realism art movement?

The primary goals were to expose social inequalities and injustices, portray the lives and dignity of ordinary people (especially the working class), advocate for social and political change, create empathy in viewers for marginalized groups, document historical conditions honestly, and make art accessible and meaningful to broad audiences rather than just wealthy collectors or art elites.

Additional Resources

Museums and Collections:

- Museum of Modern Art – Social Realism Collection – Extensive holdings of Social Realist works

- Library of Congress – FSA/OWI Photographs – Depression-era documentary photography

- Detroit Institute of Arts – Diego Rivera Murals – Rivera’s masterpiece available for viewing

Academic Resources:

- Tate Gallery – Social Realism Art Term – Comprehensive definition and history

- Metropolitan Museum of Art – American Social Realism – Educational materials and artwork collection

Documentary and Video Resources:

- Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series – PBS – Documentary on Lawrence’s iconic work

Books and Further Reading: