Few artists have captured the public’s imagination like Frida Kahlo. Her life, filled with passion, pain, and perseverance, is as intriguing as the art she created. From her bold use of color to the deeply personal themes of identity, suffering, and resilience, Kahlo’s work transcends time, making her one of the most celebrated artists of the 20th century. In this deep dive, we’ll explore Frida Kahlo’s most iconic paintings, unraveling the stories, symbolism, and emotions behind each masterpiece.

Listen to our Podcast on Frida Kahlo Iconic Paintings

This deep dive explores Frida Kahlo’s most iconic paintings, moving beyond the surface to unravel the rich, complex symbolism embedded in each masterpiece and examining her profound and enduring influence on the generations of artists who followed.

Collection of 100 + Kahlo Paintings

A Deeper Dive into Symbolism and Legacy

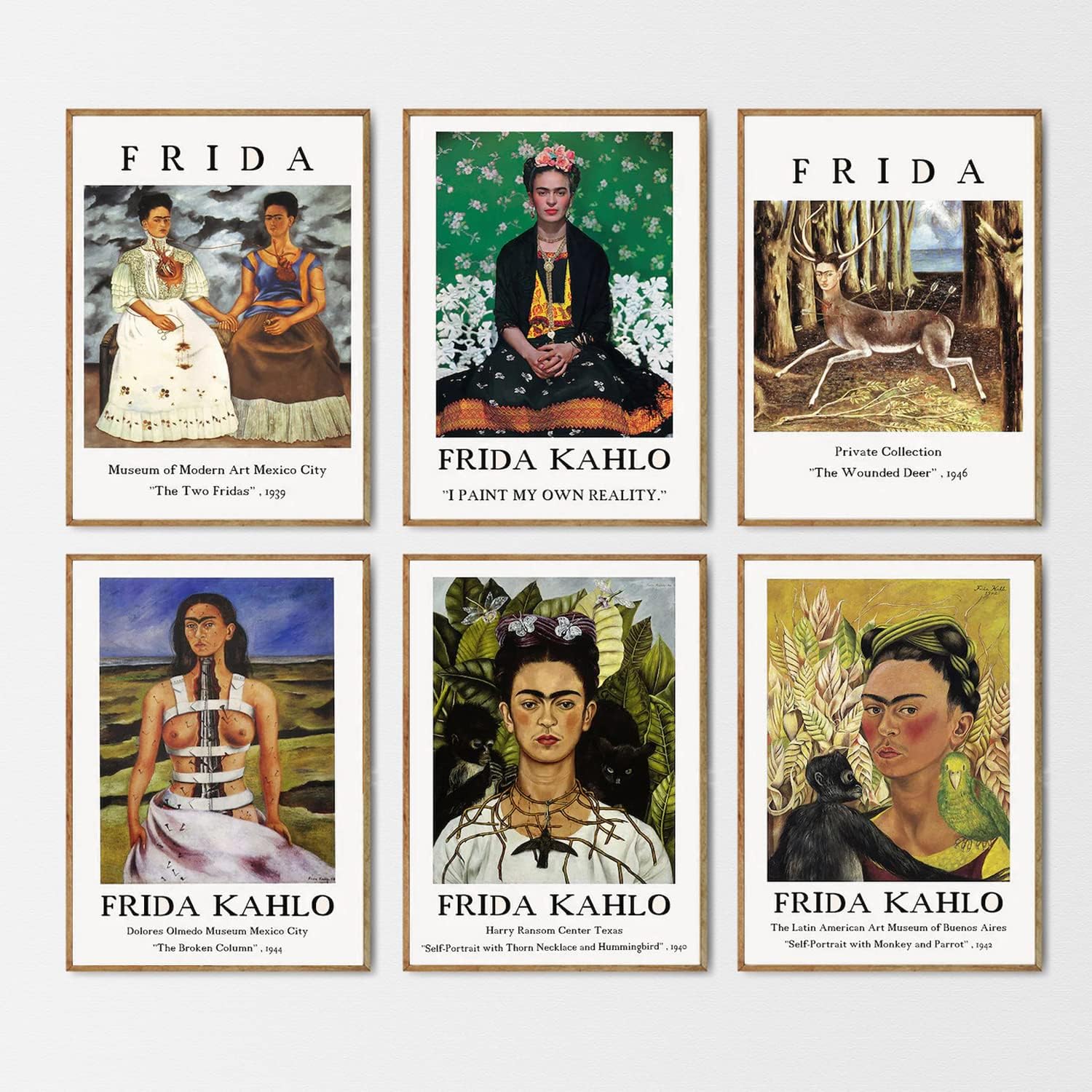

1. The Two Fridas (Las Dos Fridas) – 1939

When you think of Frida Kahlo’s iconic paintings, The Two Fridas likely comes to mind. This double self-portrait is a mesmerizing exploration of identity, heartbreak, and duality. Painted in the aftermath of her tumultuous divorce from Diego Rivera, it reveals a deeply emotional side of Kahlo, as she grapples with her inner struggles.

A Deeper Look at the Symbolism:

This painting presents two versions of Frida, seated side-by-side against a stormy, turbulent sky that mirrors her inner emotional state.

The Exposed Heart: This visceral motif is central to the painting. The two hearts are connected by a single artery, which the European Frida attempts to sever with surgical scissors, blood staining her white dress. This imagery is not just symbolic of emotional pain; it’s a direct reference to Kahlo’s lifelong battle with physical suffering and her many surgeries, blending emotional and bodily trauma into one. The act of holding hands signifies that despite the conflict, these two halves cannot exist without each other; they are both essential parts of her whole identity.

The Duality of Identity: The Frida on the right, dressed in a traditional Tehuana costume, represents the woman Rivera loved—deeply connected to her Mexican heritage. Her heart is whole and she holds a small portrait of Rivera. The Frida on the left, in a European-style Victorian dress, represents the woman Rivera abandoned. Her heart is exposed and broken.

2. Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird – 1940

Of her many self-portraits, this piece is one of the most visually arresting and symbolically dense. Kahlo confronts the viewer with a stoic, almost regal expression, starkly contrasting with the violent imagery that surrounds her.

A Deeper Look at the Symbolism:

Every element in this portrait is laden with meaning, creating a complex narrative of suffering and endurance.

The Cat and Monkey: The black cat, a traditional omen of bad luck and death, lurks over one shoulder, ready to pounce on the hummingbird. On the other shoulder is a spider monkey—a gift from Rivera. The monkey, often a symbol of lust or the devil in Mexican mythology, can be interpreted as a tender protector or a malevolent presence, reflecting the complex, dual nature of her bond with Rivera.

Crown of Thorns: The necklace of thorns digging into her neck is an unmistakable allusion to the crown of thorns worn by Christ, casting herself in the role of a martyr. It is a powerful symbol of the chronic pain she endured following a near-fatal bus accident.

The Dead Hummingbird: In Mexican folk tradition, dead hummingbirds were used as charms to bring luck in love. Here, the lifeless bird hanging from her throat symbolizes her own romantic suffering and the death of her relationship with Rivera.

3. The Broken Column – 1944

Perhaps no other painting captures the sheer physical agony that defined Kahlo’s existence like The Broken Column. Created after a spinal surgery that left her confined to a steel corset for months, this work is a brutal and honest depiction of her broken body.

A Deeper Look at the Symbolism:

The Barren Landscape: She stands alone in a desolate, fissured landscape under a gray sky. This backdrop is a reflection of her internal state—her feelings of isolation, loneliness, and the infertility that haunted her after her accident. Despite the tears streaming down her face, her gaze is direct and unbroken, a testament to her incredible resilience.

The Column and the Corset: Kahlo’s spine is replaced by a crumbling, shattered Ionic column on the verge of collapse, a direct visual metaphor for her own vertebrae. The surgical corset, which she despised, is the only thing holding her fractured body together.

The Nails: Her skin is pierced by dozens of nails of varying sizes, representing the constant, sharp pains that plagued her entire body. A larger nail piercing her heart signifies the deep emotional anguish that was inseparable from her physical suffering.

4. Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair – 1940

After her divorce from Diego Rivera, Kahlo painted Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair as a bold statement of independence and defiance. In this portrait, Kahlo sits in an oversized suit, holding a pair of scissors, her once-flowing hair scattered around her. The shift in her appearance is jarring, and the painting serves as a powerful commentary on gender and identity.

Symbolism and Interpretation

By cutting her hair and wearing a masculine suit, Kahlo challenges traditional gender norms and asserts her autonomy after the end of her marriage. The lyrics above her head, taken from a popular Mexican song, read:

“Look, if I loved you, it was for your hair. Now that you are without it, I no longer love you.”

Kahlo’s act of cutting her hair can be seen as a rejection of societal expectations and Rivera’s influence over her life. It is a visual declaration of her independence and a rejection of the feminine image that Rivera adored.

5. Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed) – 1932

This harrowing work is one of the first artistic representations of a miscarriage. Painted on a metal sheet in the style of a Mexican retablo (a devotional folk painting), Kahlo documents the trauma of losing a child while in Detroit with Rivera.

A Deeper Look at the Symbolism:

Lying naked and bleeding on a hospital bed, Kahlo is tethered by red, umbilical-like ribbons to six floating objects, each representing a facet of her pain.

Her Fractured Body: A snail symbolizes the agonizingly slow pace of the miscarriage, while a fractured pelvic bone directly references the injuries that made carrying a child to term impossible.

A Male Fetus: The central figure is a perfectly formed male child, the son she called “Dieguito” that she so desperately wanted.

An Orchid: A purple orchid, a gift from Diego, appears wilted and funereal, symbolizing a tainted sexuality and love within the context of this loss.

Medical Instruments: An autoclave for sterilizing surgical tools represents the cold, mechanical, and ultimately futile nature of the medical procedures she endured.

6. Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States – 1932

During her time in the United States, Kahlo felt disconnected from the culture and longed to return to Mexico. In Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States, she captures this feeling of duality and disconnection by placing herself between two distinct worlds.

Symbolism and Interpretation

In this painting, Kahlo stands on a pedestal between the rich, vibrant culture of Mexico on the left and the industrialized, mechanical world of the United States on the right. In one hand, she holds a small Mexican flag, while in the other, she holds a cigarette, suggesting her ambivalence toward both worlds.

The contrast between the two sides of the painting is striking. Mexico is depicted as a land of fertility, with lush plants, Aztec ruins, and the sun and moon overhead, symbolizing life and tradition. In contrast, the United States is shown as a cold, industrial world, with smokestacks, machines, and the American flag flying over skyscrapers. This painting reflects Kahlo’s deep connection to her Mexican heritage and her discomfort with the American way of life.

7. What the Water Gave Me – 1938

What the Water Gave Me is one of Kahlo’s most enigmatic and surreal paintings. In this dreamlike piece, she presents a bathtub filled with water, with various symbolic figures and scenes emerging from the water’s surface.

Symbolism and Interpretation

In this painting, Kahlo’s legs are submerged in the water, with only her toes visible above the surface. The water is filled with surreal and symbolic images, including a lifeless body, a volcano, flowers, a skyscraper, and a nude couple. These elements reflect Kahlo’s memories, fears, and fantasies, blending reality and imagination.

The painting’s title suggests that the water offers Kahlo not peace, but a torrent of unsettling memories and emotions. It is a deeply personal work, one that invites viewers to explore the depths of Kahlo’s subconscious.

A Legacy Forged in Paint: Kahlo’s Enduring Influence

Frida Kahlo’s impact stretches far beyond her own canvases. Her radical honesty and revolutionary spirit have cemented her status as a pivotal figure in art history, inspiring countless artists and social movements.

The Feminist Icon

Decades before the feminist art movement gained momentum, Kahlo was creating work that was unapologetically female-centric. She defied traditional beauty standards by exaggerating her unibrow and mustache in her portraits, challenging the narrow confines of femininity. More profoundly, she broke cultural taboos by depicting the raw, often painful realities of the female experience—miscarriage, childbirth, and infertility—at a time when such topics were considered private and shameful. In paintings like Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, where she dons a man’s suit after her divorce, she powerfully subverts gender roles, making a bold statement about autonomy and identity.

The Godmother of Chicana Art

For Chicana artists in the United States, Kahlo became a powerful symbol of cultural pride and resistance. In the 1970s, artists of the Chicano Movement, seeking to affirm their cultural heritage, looked to Kahlo as an ancestor. They celebrated her unapologetic embrace of her Mexicanidad (Mexican identity), her use of indigenous symbolism, and her fusion of folk traditions with a modern, political consciousness. Artists like Rupert Garcia and Ester Hernandez reclaimed her image, elevating her to an icon of bicultural identity and female strength.

Influence on Contemporary Artists

Kahlo’s legacy is alive in the work of numerous contemporary artists who explore themes of the body, trauma, identity, and confession.

- Marina Abramović: The celebrated performance artist, whose work often involves enduring extreme physical pain to explore resilience and the limits of the body, shares a clear lineage with Kahlo’s visual martyrdom in paintings like The Broken Column.

- Tracey Emin: Known for her deeply personal and confessional art, Emin’s work echoes Kahlo’s transformation of private trauma into public art, breaking down the barriers between the artist’s life and their work.

- Wangechi Mutu: This Kenyan-American artist creates powerful collages that deconstruct the female form to explore themes of post-colonialism, race, and gender. Her work continues the dialogue Kahlo started about hybrid identity and the politics of the female body.

Galleries displaying Frida Kahlo Artworks

| Gallery | Location | Exhibition Details |

|---|---|---|

| Grand Palais Immersif | Paris, France | “Frida Kahlo ¡Viva La Vida!” exhibition from September 18, 2024 to March 2, 2025. Features 360-degree projections and animations. |

| Frida Kahlo Museum (Casa Azul) | Mexico City, Mexico | Permanent exhibition in Kahlo’s former home, featuring her artwork and personal belongings. |

| Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño | Mexico City, Mexico | Permanent exhibition with several paintings and drawings by Frida Kahlo. |

| The Museum of Modern Art | Mexico City, Mexico | Permanent collection includes artworks by Frida Kahlo. |

| The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) | New York City, USA | Houses Kahlo’s works in its permanent collection, including “Fulang-Chang and I”. |

| National Museum of Women in the Arts | Washington D.C., USA | Features Kahlo’s “Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky” |

Conclusion: Frida Kahlo’s Enduring Legacy

Frida Kahlo’s iconic paintings are more than just beautiful works of art – they are visual diaries that chronicle her physical and emotional journey. Through her bold use of color, symbolism, and surrealism, Kahlo created a body of work that is deeply personal yet universally relatable. Her paintings resonate with themes of identity, pain, love, and resilience, making her one of the most influential and beloved artists of all time.

Be Inspired!

Kahlo’s work continues to inspire generations of artists and art lovers, reminding us that art is not just about beauty – it’s about truth, vulnerability, and the courage to express the deepest parts of ourselves. Whether through the haunting symbolism of The Two Fridas or the raw emotion of The Broken Column, Frida Kahlo’s paintings remain as powerful and relevant today as they were when she first created them.

References:

- Frida Kahlo: 100 Paintings Analysis, Biography, Quotes, & Art

This site offers a comprehensive analysis of Kahlo’s works, including her self-portraits and the themes of pain and identity that permeate her art. It details her most significant paintings and the personal experiences that influenced them. The site also includes quotes from Kahlo, providing context for her artistic vision. - 10 Frida Kahlo Paintings and the Symbolism Behind Them

This article explores ten of Kahlo’s most famous paintings, delving into the symbolism and emotional depth of each piece. It highlights how her personal experiences, such as her tumultuous relationship with Diego Rivera, are reflected in her art. The site provides a rich context for understanding the significance of her work. - The Hidden Meanings In Frida Kahlo’s Paintings

This resource focuses on the hidden details and symbolism in Kahlo’s self-portraits, revealing deeper insights into her life and thoughts. It discusses specific paintings and their meanings, showcasing how Kahlo used her art as a form of expression to convey complex ideas and emotions.