The conceptual art movement changed everything we thought we knew about art. Starting in the 1960s, a group of brave artists decided that the idea behind artwork was more important than the painting, sculpture, or any physical object you could hold. This revolutionary thinking turned the art world upside down and created a new way of understanding what art could be.

Key Points Summary

- What it is: An art movement where ideas matter more than physical objects

- When it happened: Mid-1960s to mid-1970s (though it continues to influence artists today)

- Main goal: Challenge traditional definitions of art and question the art world’s commercial focus

- Key principle: “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art” – Sol LeWitt

- Legacy: Foundation for most contemporary art practices we see today

What Made the Conceptual Art Movement So Revolutionary?

The conceptual art movement didn’t just create new artworks—it completely redefined what art could be. By prioritizing the idea or concept behind the work over its physical form, conceptual artists dismantled conventional artistic hierarchies and forced people to think differently about creativity.

Before conceptual art, most people expected art to be something beautiful they could see and touch. A painting needed paint, a sculpture needed stone or metal. But conceptual artists said, “What if the most important part of art is the thought behind it?”

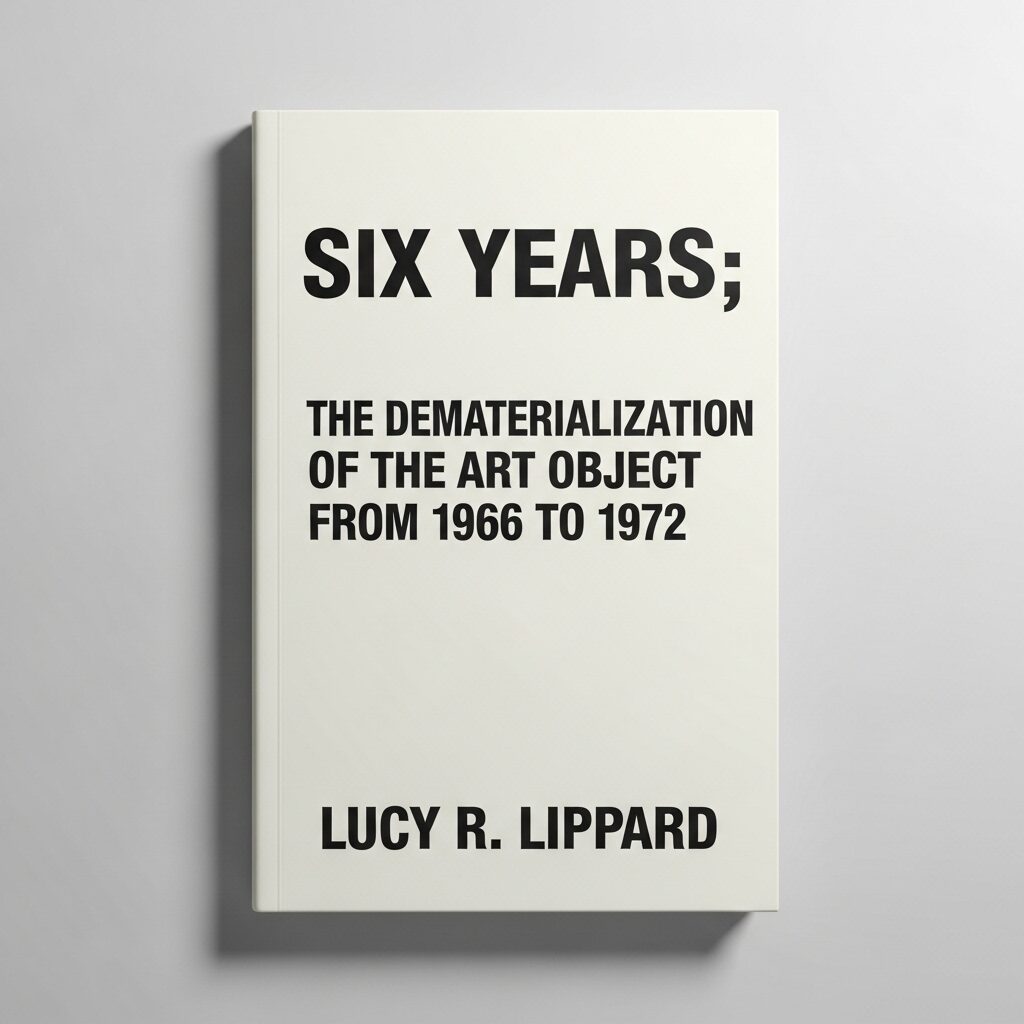

The “Dematerialization” of Art Objects

This term, famously coined by critic Lucy Lippard in her book Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, referred to the de-emphasis on the physical object in favor of the idea. Artists wanted to create works that couldn’t be easily bought and sold, challenging the commercial art market.

Think of it this way: if you write down an instruction like “Draw a line from one corner of the wall to the other,” that instruction IS the artwork. Anyone can follow it, but the artistic genius lies in thinking of the idea in the first place.

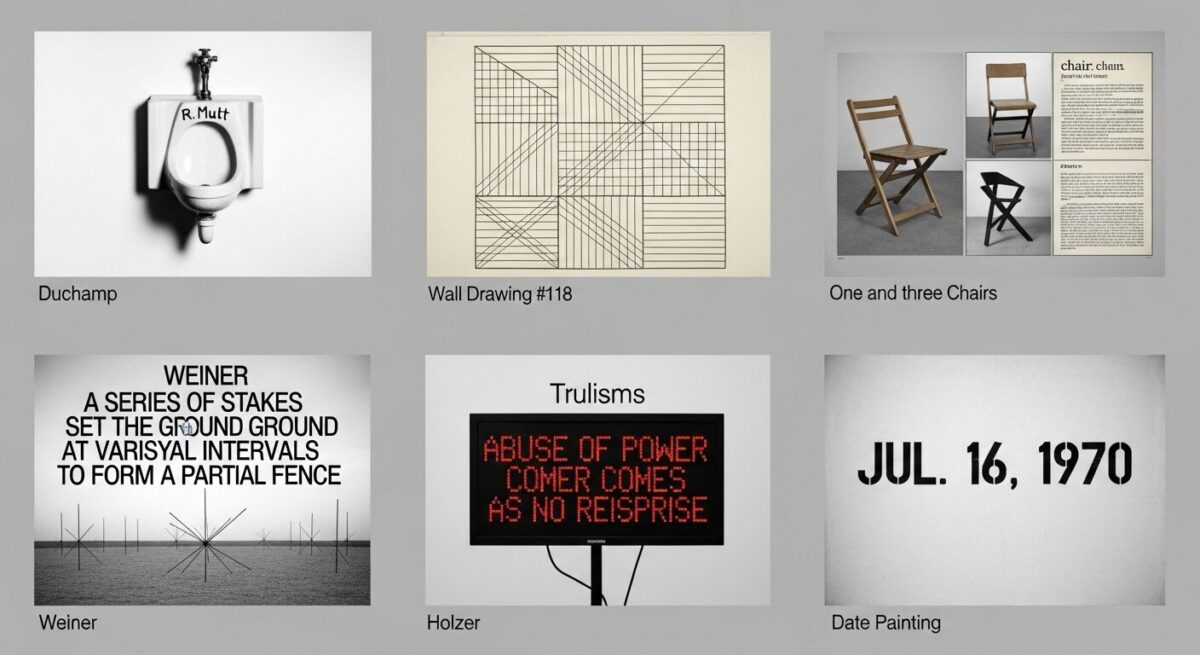

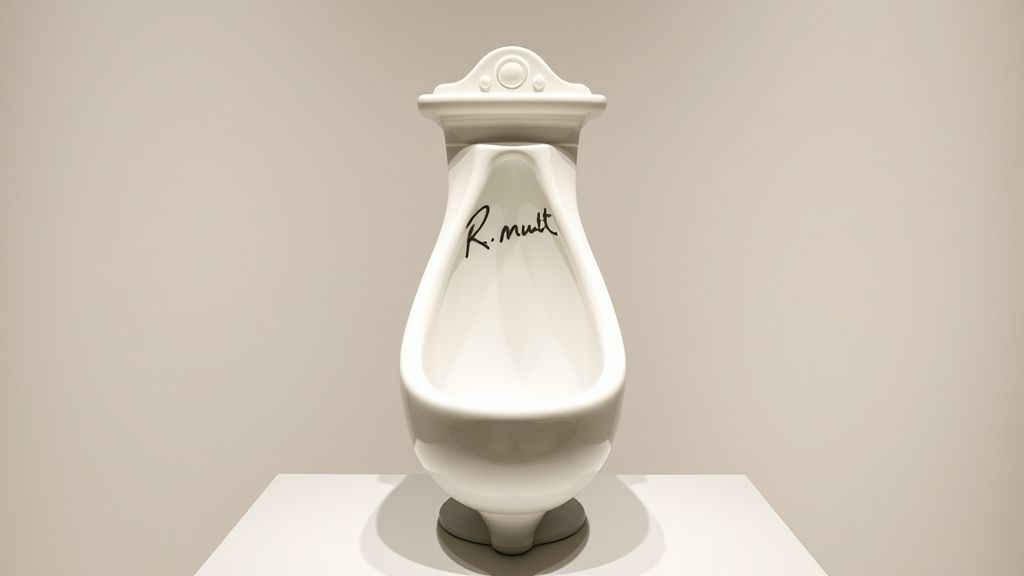

The Philosophical Roots: Marcel Duchamp’s Revolutionary Impact

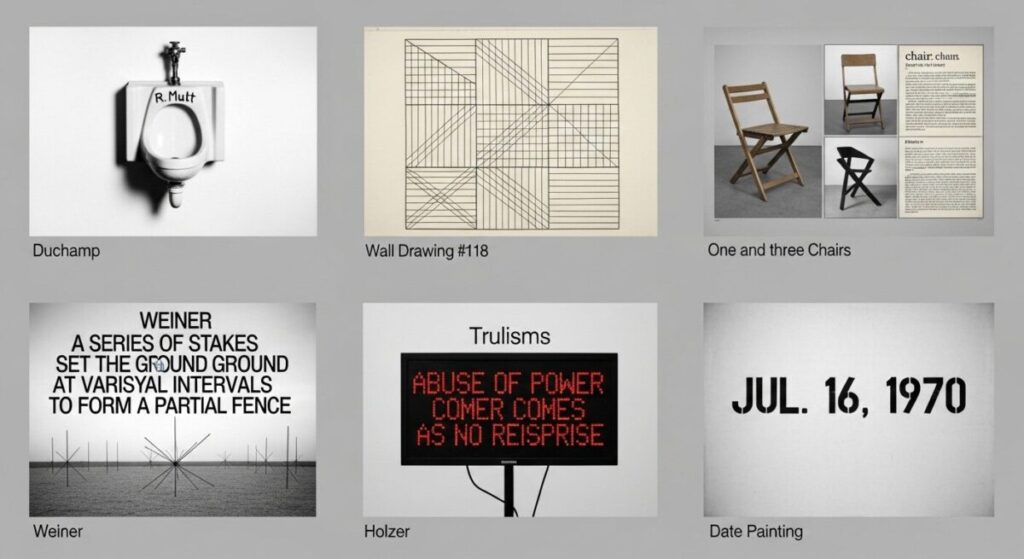

Every artistic revolution needs a pioneer, and for conceptual art, that person was Marcel Duchamp. In 1917, he took an ordinary urinal, signed it “R. Mutt,” and submitted it to an art exhibition under the title “Fountain.”

By taking a mass-produced porcelain urinal, signing it “R. Mutt,” and submitting it to an exhibition, Duchamp performed a radical act of artistic re-contextualization. He wasn’t showing off his painting skills or sculpting abilities. Instead, he was asking a simple but profound question: “Who decides what counts as art?”

This single act planted the seeds for the entire conceptual art movement. It showed that art could be about making people think rather than making beautiful objects.

Key Artists Who Shaped the Conceptual Art Movement

The conceptual art movement produced several groundbreaking artists who each approached the “idea over object” philosophy in their own unique way.

Sol LeWitt: The Master of Instructions

Sol LeWitt became famous for his “Wall Drawings”—but here’s the twist: he didn’t actually draw them himself. Instead, LeWitt wrote detailed instructions that others could follow to create the artworks.

“The idea becomes a machine that makes the art” was LeWitt’s famous motto. He believed that the artist’s vision should be carried out “blindly” and that “the artist’s will is secondary to the process he initiates”.

Example: Wall Drawing #118 (1971) consists of instructions like “On a wall surface, any continuous stretch of wall, using a hard pencil, place fifty points at random. Using four colors of ink (red, yellow, blue, black) draw straight lines from each point to each of the other points.”

The genius? Anyone can create this artwork by following LeWitt’s instructions, but LeWitt is still considered the artist because he conceived the idea.

Joseph Kosuth: The Language Detective

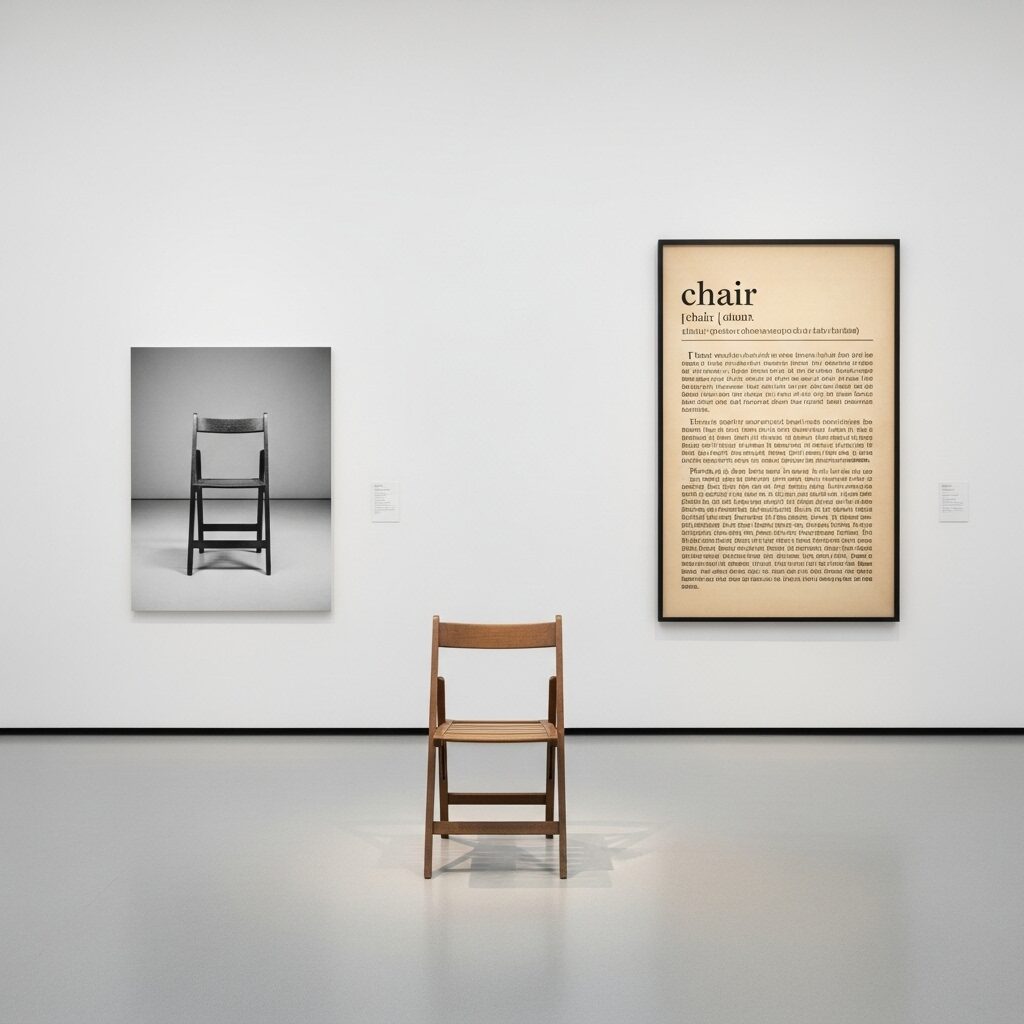

Joseph Kosuth created one of the most famous conceptual artworks ever: “One and Three Chairs” (1965). This piece includes:

- A real wooden chair

- A photograph of the same chair

- A dictionary definition of the word “chair”

The work forces the viewer to confront the nature of representation and reality. Which of the three is the “real” chair? Kosuth’s work explores how we understand objects through language and images.

Lawrence Weiner: Words as Art

Lawrence Weiner took conceptual art to its most extreme form by using only words. His artwork “A Wall Removed or Replaced” (1969) exists as just that—a statement.

“The artist may construct the piece. The piece may be fabricated. The piece need not be built. Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist, the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership” was Weiner’s revolutionary declaration.

This means you could build an actual wall, remove it, or just think about the concept—all versions are equally valid as art.

Jenny Holzer and On Kawara: Public vs. Private

The conceptual art movement was flexible enough to include completely opposite approaches:

Jenny Holzer created public art using LED signs and billboards with provocative messages like “ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE“. Her work engaged with political and social issues in highly visible public spaces.

On Kawara, in contrast, created deeply personal works like his “Today Series”—paintings featuring only the current date, created daily for nearly 50 years. His work was a deeply personal, almost meditative ritual of documenting his own existence.

How Conceptual Art Relates to Other Art Movements

Understanding the conceptual art movement becomes clearer when we see how it connects to other artistic styles and movements.

Breaking Away from Abstract Expressionism

The conceptual art movement emerged as a direct response to Abstract Expressionism, which had dominated art since World War II. Abstract Expressionism was characterized by gestural intensity, emotion, and the unique, visible “hand” of the artist.

Conceptual artists wanted the opposite: an “emotionally dry” approach that would be “mentally interesting” to the viewer, encouraging intellectual engagement over aesthetic pleasure.

The Minimalist Connection

Minimalism and conceptual art developed side by side in the 1960s and shared many ideas, but they had one crucial difference:

| Minimalism | Conceptual Art |

|---|---|

| Emphasized physical presence and industrial materials | Prioritized ideas over objects |

| Focused on the viewer’s physical experience | Focused on intellectual engagement |

| Used simple, repeated forms | Could use any materials or no materials at all |

Distinguishing from Pop Art

Both Pop Art and conceptual art emerged in the 1960s and sought to remove “the personal or emotional from their art”. However:

- Pop Art was “anti-intellectual” and “celebrates everyday objects and media icons”

- Conceptual Art was intensely intellectual, with artists sourcing ideas from fields like “philosophy, linguistics, semiotics and critical theory”

Why Conceptual Art Causes Such Strong Reactions

The conceptual art movement has always been controversial. The work was often seen as “shocking, distasteful, and conspicuously lacking in craftsmanship”. Common criticisms include:

- “Anyone could have done that”

- “The artist is faking it”

- “It’s overly intellectualized”

- “You don’t have to see it” to respond to it

But here’s the important point: this “divisive character” was “far from accidental”. Conceptual art “actively sets out to be controversial” and “challenge[s] and probe[s] us about what we tend to take as given in the domain of art”.

Whether conceptualism is met with admiration, disdain, or confusion (often than not); it’s done its job as proper art to render a reaction from its audience.

The Political Dimension

The conceptual art movement wasn’t just about art theory—it was also deeply political. The movement reflected a “strong socio-political dimension” and “wider dissatisfaction with society and government policies” that characterized the 1960s and 70s.

The famous “Information” exhibition at MoMA in 1970 included:

- Hans Haacke’s poll about the Vietnam War

- John Giorno’s Dial-a-Poem (which attracted FBI surveillance)

- Various works protesting museum governance

The Lasting Impact of the Conceptual Art Movement

Conceptual art is widely considered to be “the turning point from Modern to Contemporary Art practice”. Its influence can be seen in many subsequent art movements:

Institutional Critique

Artists began using museums and galleries themselves as subjects and materials for their work, directly questioning how art institutions operate.

Performance and Land Art

These movements use ephemeral actions and the natural environment as a vehicle for conceptual expression, with documentation serving as a key component.

Relational Aesthetics

This 1990s movement focuses on art as a set of human relations and social contexts, viewing the artist as a facilitator and art as “information exchanged between the artist and the viewers”.

Digital and Internet Art

The concept of dematerialization is even more relevant today, with the “immaterial” nature of the internet and “the cloud” still relying on the material infrastructure of servers and data centers.

Understanding Conceptual Art in Today’s World

The principles of the conceptual art movement are more relevant than ever in our digital age. When we create and share memes, post on social media, or engage with virtual reality, we’re participating in forms of “dematerialized” communication that conceptual artists predicted decades ago.

Many contemporary artists continue to work with conceptual approaches. Artists who clearly use various techniques and strategies associated with Conceptual art include Jenny Holzer and her use of language, Sherrie Levine and her photographic critique of originality, Cindy Sherman and her play with identity, and Barbara Kruger’s use of text and photography.

Major Conceptual Artworks You Should Know

| Artist | Artwork | Year | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marcel Duchamp | Fountain | 1917 | Defined the art object by conceptual choice rather than craftsmanship |

| Sol LeWitt | Wall Drawing #118 | 1971 | Emphasized the idea over execution; challenged notions of authorship and originality |

| Joseph Kosuth | One and Three Chairs | 1965 | Used an everyday object to explore the relationship between language, image, and reality |

| Lawrence Weiner | A Wall Removed or Replaced | 1969 | Used language as the primary medium; empowered the viewer as co-creator |

| Jenny Holzer | Truisms | 1977-79 | Used text in public spaces to provoke social and political critique |

| On Kawara | Today Series | 1966-2015 | A systematic, private documentation of time, life, and existence |

How to Appreciate Conceptual Art

If you’re new to conceptual art, here are some tips for understanding and appreciating it:

- Focus on the idea, not the object: Ask yourself, “What is the artist trying to make me think about?”

- Consider the context: When was this made? What was happening in society at the time?

- Think about the process: How was this artwork created? Who was involved?

- Question your assumptions: What do you expect art to be? Why do you expect that?

- Embrace intellectual engagement: Conceptual art rewards thinking over feeling.

Visiting Conceptual Art in Museums

You can experience conceptual art at major museums worldwide:

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York – Houses works by Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, and Lawrence Weiner

- Tate Modern, London – Features rotating exhibitions of conceptual works

- Whitney Museum, New York – Strong collection of American conceptual art

- Centre Pompidou, Paris – European perspective on the movement

Frequently Asked Questions About Conceptual Art

What is conceptual art in simple terms?

Conceptual art is a term that came into use in the late 1960s to describe a wide range of types of art that elevated the concept or the idea behind the work over traditional aesthetic and material concerns. Simply put, it’s art where the thought behind the work is more important than how it looks.

Why is conceptual art so hard to understand?

Conceptual art gets a bad rap. It’s the butt of endless jokes because it challenges what people expect from art. Instead of creating something beautiful to look at, conceptual artists create ideas to think about, which requires more mental effort from viewers.

Is conceptual art still relevant today?

Yes! Well-known contemporary artists such as Mike Kelley or Tracey Emin are sometimes labeled “second- or third-generation” conceptualists, or “post-conceptual” artists. The movement’s influence can be seen in everything from social media art to interactive installations.

Can anyone make conceptual art?

Some works of conceptual art may be constructed by anyone simply by following a set of written instructions. However, the artistic genius lies in conceiving the original idea, not necessarily in executing it.

What’s the difference between conceptual art and regular art?

Traditional art emphasizes skill, beauty, and the physical object. Conceptual art prioritizes the idea behind the work and often questions what art should be or do in society.

Why did conceptual artists reject traditional art?

Conceptual artists wanted to critique the commercialization of the art world and challenge established definitions of artistic value. They believed art should make people think rather than just appreciate beauty.

The Future of Conceptual Art

The conceptual art movement established principles that continue to evolve with technology and social change. As we move deeper into the digital age, questions about what constitutes art, who can be an artist, and how ideas can be shared become increasingly relevant.

The movement’s core insight—that ideas can be as valuable as objects—seems prophetic in an age where information and concepts drive our economy and culture. From blockchain art to AI-generated works, contemporary artists continue to explore the boundary between idea and object that conceptual artists first questioned in the 1960s.

The conceptual art movement remains one of the most influential and challenging developments in art history. By asking us to value thoughts over things, ideas over objects, and questions over answers, it fundamentally changed how we understand creativity and artistic expression. Whether you love it or find it frustrating, conceptual art accomplished its primary goal: it made us think differently about art itself.

Additional Resources

Museums and Institutions

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) – Conceptual Art Collection

- Tate Modern – Conceptual Art Definition

- Whitney Museum of American Art

Academic Resources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Conceptual Art

- The Art Story – Conceptual Art Movement Overview

Books and Publications

- “Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object” by Lucy Lippard

- “Conceptual Art” by Tony Godfrey

Contemporary Resources

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to the conceptual art movement, from its revolutionary origins to its continuing influence on contemporary art. Understanding this movement helps us appreciate how ideas themselves can be powerful forms of artistic expression.