Modern art – bold, abstract, and endlessly debated – didn’t spring into existence out of nowhere. It’s a story of daring creativity and rebellion, deeply intertwined with the roots of modern art . Visionaries like Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, and Frida Kahlo didn’t just redefine artistic expression; they ignited a revolution by weaving together a vibrant mosaic of influences.

From classical traditions to global cultures, and from the seismic societal shifts of their era to deeply personal human experiences, these trailblazers tapped into something timeless yet transformative. But what truly fueled their groundbreaking works? Join us as we dive into the historical currents, avant-garde movements, and profound inspirations that gave birth to modern art—a testament to innovation firmly rooted in the echoes of the past.

Key Points Summary

- Classical Traditions: Modern artists like Picasso and Matisse reinterpreted Renaissance and Romantic techniques, blending them with new ideas.

- Global Cultures: African, Asian, and Indigenous art inspired groundbreaking styles, from Cubism to Kahlo’s vibrant symbolism.

- Societal Shifts: War, industrialization, and personal identity drove movements like Dadaism, Futurism, and Expressionism.

Classical Foundations: Renaissance, Romanticism, and Beyond

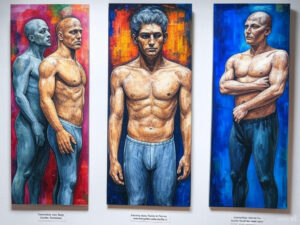

Modern artists didn’t reject tradition outright—they reinterpreted it. The Renaissance, with its emphasis on anatomy, perspective, and humanism, left a lasting imprint. Pablo Picasso’s groundbreaking Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) exemplifies this dialogue. The painting’s jagged forms owe a debt to Michelangelo’s muscular figures, while its distorted proportions echo El Greco’s elongated, expressive style. Picasso didn’t merely copy; he fractured these classical ideals into something raw and new, signaling Cubism’s arrival.

Henri Matisse, another titan of modernism, found inspiration in Romanticism’s emotional intensity. His vivid, unblended colors in works like The Dance (1910) recall Eugène Delacroix’s dramatic palettes, where hues carried psychological weight. Matisse transformed this tradition into a language of pure sensation, prioritizing feeling over realism.

Even abstractionists leaned on history. Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of non-representational art, drew from medieval religious icons. His treatise Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1911) reveals how he used color—like the golds and blues of Byzantine mosaics—to evoke spiritual resonance. The Guggenheim’s analysis of his work underscores this link, showing how ancient symbolism fueled his abstract visions. These artists prove that modern art, even at its most radical, was a conversation with the past.

Roots of Modern Art: Global Art Movements

The 20th century marked a seismic shift as artists looked beyond Europe’s borders, embracing global traditions that enriched their practices. This wasn’t mere exoticism—it was a profound redefinition of art itself.

African Tribal Art

Picasso’s encounter with African masks at Paris’s Trocadéro Museum in 1907 was a turning point. Their fragmented planes and stark geometries inspired Cubism’s angular aesthetic, evident in Les Demoiselles. The Met’s collection of African art highlights this influence, showing how tribal sculptures’ abstracted forms challenged Western notions of representation. Artists like Amedeo Modigliani also adopted these elongated shapes, blending them with European portraiture.

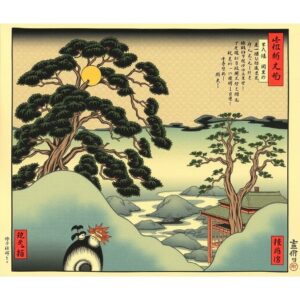

Japanese Ukiyo-e Prints

Across the Atlantic, Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet fell under the spell of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints. These works, with their flat compositions, bold outlines, and everyday subject matter, offered a stark contrast to Western realism. Van Gogh’s Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Orchard (1887) mimics their asymmetry, while Monet’s water lily series reflects their serene simplicity. This cross-pollination broadened Impressionism’s scope, proving art could thrive without depth or shadow.

Mexican Folk Art and Indigenous Traditions

Frida Kahlo’s work exemplifies how Indigenous cultures shaped modern art. Her paintings—like The Two Fridas (1939)—weave Mexican folk motifs, such as vibrant textiles and pre-Columbian symbols, into deeply personal narratives. As MoMA notes, Kahlo fused these elements with her physical and emotional pain, creating a visual language that was both intimate and political. Her art elevated local traditions to the global stage, challenging the dominance of European canons.

This global fusion didn’t just diversify modern art—it dismantled the idea of “high art” as a Western privilege, inviting a broader, more inclusive creative dialogue.

Society in Turmoil: Reflecting a Changing World

Modern art wasn’t just shaped by other art—it mirrored the chaos and transformation of its era. Three forces stand out: war, industrialization, and identity.

World War I and the Birth of Dadaism

The carnage of World War I (1914–1918) shattered faith in progress, giving rise to Dadaism. This anti-art movement, spearheaded by Marcel Duchamp, embraced absurdity as a response to a senseless world. Duchamp’s Fountain (1917) – a urinal signed “R. Mutt” – mocked artistic norms and questioned beauty’s very definition. Dadaism’s irreverence was a direct product of war’s disillusionment, proving art could be a weapon of critique.

The Industrial Revolution and Futurism

As machines reshaped society, artists responded. The Italian Futurists, led by Umberto Boccioni, celebrated technology’s speed and power. Boccioni’s sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) captures motion in bronze, embodying the era’s obsession with progress. Yet, this optimism soured as industrialization’s downsides—alienation, pollution—became clear, influencing later artists like Fernand Léger, who depicted workers as mechanized figures.

Personal Struggles and Political Expression

For Frida Kahlo, art was a crucible for identity. Her self-portraits, like Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), blend Mexican heritage with raw emotion, confronting gender norms and colonial legacies. Her work aligns with Expressionism’s focus on inner turmoil, seen in Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893), but Kahlo’s political edge—tied to Mexico’s revolutionary spirit—sets her apart. Modern art became a platform for voices long silenced by tradition.

Traditional vs. Modern Inspirations: A Side-by-Side Comparison

To grasp modern art’s evolution, consider this contrast:

| Traditional Influences | Modern Inspirations |

|---|---|

| Biblical scenes (Renaissance) | Personal identity (Frida Kahlo) |

| Realistic portraits | Abstract symbolism (Kandinsky) |

| European art canon | Global motifs (African/Asian) |

| Oil paints, marble | Industrial materials (Duchamp) |

This table reveals a shift from collective narratives to individual and global perspectives, from revered mediums to experimental ones. Modern artists didn’t abandon tradition—they remade it.

The Science of Influence: Psychology and Philosophy

Beyond art and society, modernists drew from emerging ideas. Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis influenced Surrealists like Salvador Dalí, whose The Persistence of Memory (1931) probes the subconscious with melting clocks. Meanwhile, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s “God is dead” ethos resonated with Existentialist undertones in Alberto Giacometti’s skeletal figures, reflecting humanity’s search for meaning. These intellectual currents gave modern art a depth that transcended aesthetics.

Legacy of Modern Art: Why It Still Resonates

Modern artists were cultural alchemists, transforming diverse influences—Renaissance techniques, African sculptures, war’s wreckage—into something new. Their work proves creativity thrives on collision: of cultures, ideas, and histories. Today, this legacy lives in digitized collections like Tate Modern’s archives or MoMA’s online exhibits, where you can trace these threads yourself. Jackson Pollock’s drips, for instance, echo Kandinsky’s abstraction, while street art owes a debt to Kahlo’s bold iconography.

This diversity isn’t just historical trivia—it’s a blueprint for innovation. Modern art challenges us to see the world through others’ eyes, a lesson as vital now as it was then.

Conclusion: The Timeless Dialogue of Art

Every brushstroke by Pollock, every fracture in Picasso’s forms, whispers a story of cross-cultural exchange and human resilience. Modern art isn’t rebellion for its own sake – it’s a testament to how history, globalism, and personal grit forge genius. It’s a dialogue that spans centuries and continents, inviting us to listen. Ready to dig deeper into the roots of modern art? Explore the links to The Met, MoMA, The Guggenheim, and Tate Modern, and join the conversation shaping art’s next chapter.