When Pablo Picasso began painting faces from multiple angles at once, he didn’t just change art—he completely reimagined how we could see the human form. His abstract faces challenged everything people thought they knew about portraits, showing eyes from the front while noses appeared in profile, creating a visual puzzle that continues to fascinate art lovers over a century later. These groundbreaking works transformed Picasso from an already talented artist into one of history’s most influential painters.

Key Points:

- Picasso’s abstract faces revolutionized portrait painting by showing multiple perspectives simultaneously

- Cubist techniques allowed him to fragment and reassemble facial features in innovative ways

- His approach was influenced by African masks and Cézanne’s geometric compositions

- Famous examples include “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” and the “Weeping Woman” series

- These techniques influenced countless modern and contemporary artists

Understanding Picasso’s Journey to Abstract Faces

Pablo Picasso didn’t start painting strange, fractured faces right away. Born in 1881 in Málaga, Spain, he began his artistic journey creating realistic portraits that would have made any traditional art teacher proud. His early works from the Blue Period and Rose Period showed he could paint conventionally beautiful faces with impressive skill. But Picasso wasn’t interested in simply copying what his eyes saw—he wanted to show what his mind understood about the three-dimensional human face on a two-dimensional canvas. The transformation began around 1907 when Picasso encountered African and Iberian sculptures in Paris. These masks, with their simplified geometric forms and expressive power, sparked something revolutionary in his imagination. Unlike European portrait traditions that emphasized realistic beauty and proportion, African art presented faces as bold, symbolic forms that communicated emotion and meaning through abstraction rather than accuracy.

Around the same time, Picasso studied the work of Paul Cézanne, who had begun breaking down landscapes and still lifes into geometric shapes. Cézanne’s approach to showing objects from slightly different angles gave Picasso a crucial insight: what if you could show a person’s face from the front and side at the same time? This question would become the foundation of Cubism and change portrait painting forever.

What Makes a Face “Abstract” in Picasso’s Style?

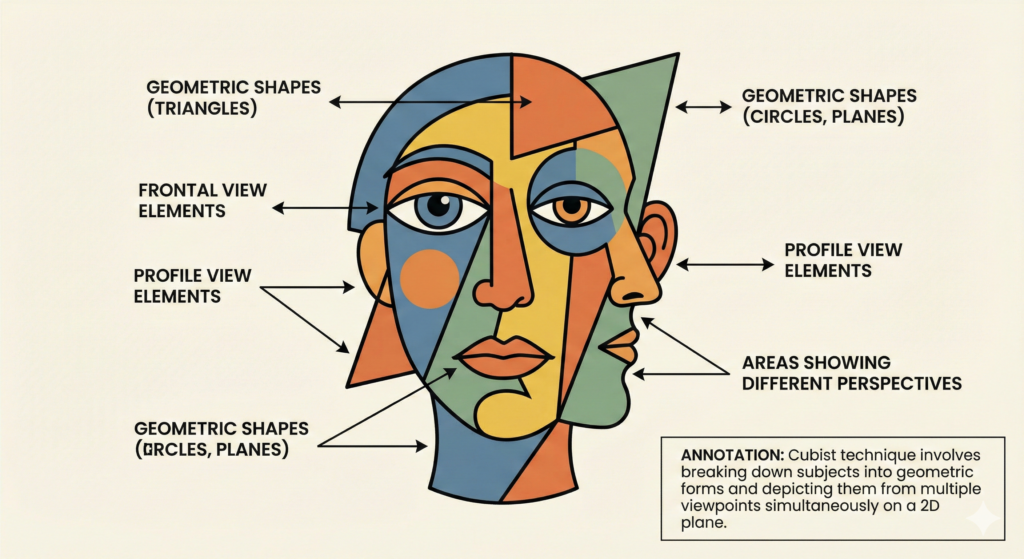

When we talk about Picasso’s abstract faces, we’re describing a radical departure from traditional portraiture. Instead of painting what a face looks like from one fixed viewpoint, Picasso deconstructed faces into their essential components—eyes, nose, mouth, chin—and then reassembled them in ways that showed multiple perspectives simultaneously.

Think of it like this: normally, when you look at someone’s face straight on, you see both eyes facing you, but you can’t see their profile. When you look at them from the side, you see the profile but only one eye. Picasso thought, “Why choose?” His abstract faces might show both eyes facing forward while the nose appears in profile, or one side of the face might be lighter while the other is darker, representing different times of day or different emotional states.

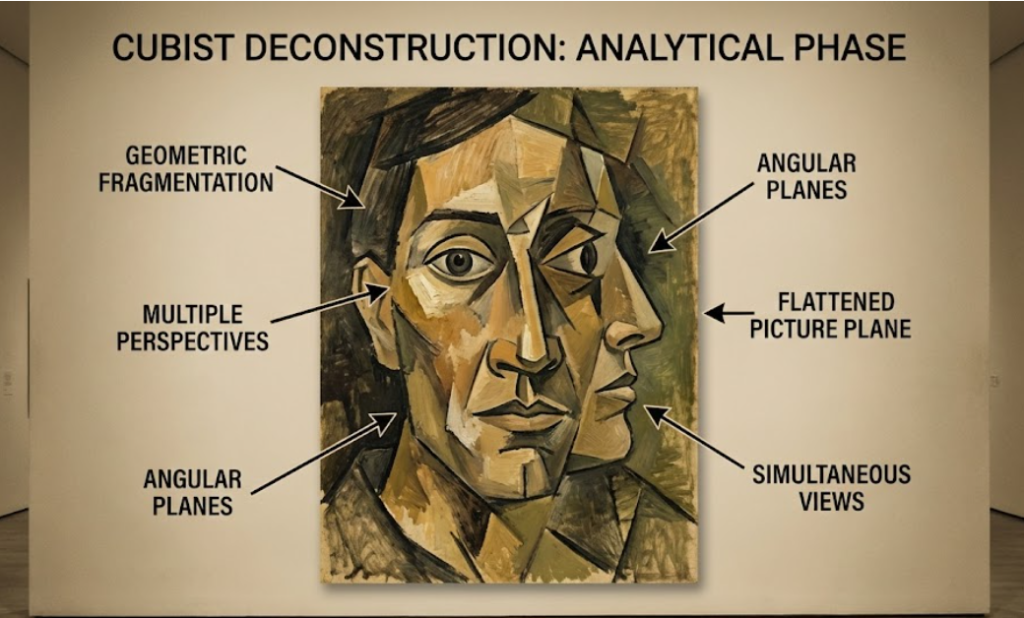

Key Characteristics of Picasso’s Abstract Faces

Fragmentation and Geometric Shapes Picasso broke faces down into geometric forms—triangles for noses, circles for eyes, angular planes for cheeks and foreheads. This wasn’t random chaos; it was a calculated way to show the essential structure of a face. The geometric approach gave his portraits a monumental, almost architectural quality that made them feel both ancient and futuristic.

Multiple Perspectives Perhaps the most famous aspect of Cubist portraiture is simultaneous perspective. A single face might combine frontal, profile, and three-quarter views all at once. This technique let Picasso capture more information about his subject than any single photograph ever could.

Flattened Picture Plane Traditional portraits created the illusion of three-dimensional depth. Picasso did the opposite, flattening the picture plane so that all the different angles and views existed on the same surface level. This made his portraits feel more like relief sculptures than painted images.

Expressive Distortion Beyond simply showing multiple angles, Picasso exaggerated and distorted facial features to convey emotion. Eyes might be different sizes, mouths could stretch across unusual positions, and faces might appear melted or fractured to express psychological states.

The Evolution of Picasso’s Face Paintings

Early Cubism: Analytical Period (1907-1912)

Picasso’s first major abstract face composition appeared in “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907), a massive painting of five female figures that shocked the art world. The faces in this painting, especially the two on the right, showed clear influence from African masks with their angular, geometric construction. The women’s faces appeared both primitive and modern, beautiful and disturbing.

During the Analytical Cubism phase, Picasso and his collaborator Georges Braque developed a monochromatic palette dominated by browns, grays, and ochres. The faces they painted during this period became increasingly fragmented, sometimes barely recognizable as human features. Portrait subjects might appear as a collection of intersecting planes and facets, like looking at a face through a shattered mirror where each piece shows a slightly different angle.

The painting “Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler” (1910) exemplifies this approach. Kahnweiler was Picasso’s art dealer and friend, but in this portrait, his face has been completely deconstructed into a complex arrangement of geometric planes. You can identify elements – perhaps an eye here, a hint of a nose there—but the overall effect is more like a three-dimensional map of a face than a traditional portrait.

Synthetic Cubism (1912-1919)

As Cubism evolved, Picasso began incorporating collage elements and returned to using brighter colors. During the Synthetic Cubism phase, faces became simpler and more decorative. Rather than breaking down observed reality, Picasso now synthesized faces from simple shapes, patterns, and even real materials like newspaper clippings and wallpaper.

The portraits from this period often feel more playful and accessible. Facial features might be represented by just a few bold lines or colored shapes, yet they remained unmistakably faces. This simplified approach influenced everything from advertising design to comic art in the decades that followed.

Later Abstract Portraits (1920s-1970s)

Picasso never stopped experimenting with how to paint faces. Throughout his long career, he returned again and again to the human face as a subject for innovation. His later portraits often combined his Cubist techniques with surrealist distortion and emotional intensity.

The “Weeping Woman” series (1937), created during the Spanish Civil War, shows faces torn apart by grief. These paintings use fragmented Cubist techniques not just for formal experimentation but to express raw emotion. The face becomes a battleground of clashing shapes and colors, perfectly capturing psychological anguish.

His portraits of his various lovers and wives—Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot, and Jacqueline Roque—each show different approaches to abstraction. Some are gentle and curvilinear, others harsh and angular. The way Picasso painted a woman’s face often reflected his emotional relationship with her at the time.

Famous Examples of Picasso’s Abstract Faces

| Painting Title | Year | Key Features | Historical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Les Demoiselles d’Avignon | 1907 | African mask influence, angular features | Launched Cubist movement |

| Portrait of Ambroise Vollard | 1910 | Extreme fragmentation, monochromatic | Peak Analytical Cubism |

| Girl Before a Mirror | 1932 | Bright colors, profile and frontal view combined | Mature synthetic style |

| Weeping Woman | 1937 | Emotional distortion, war commentary | Political and emotional depth |

| Portrait of Dora Maar | 1937 | Split face technique, psychological intensity | Master portrait synthesis |

How to “Read” a Picasso Abstract Face

Looking at a Picasso abstract face for the first time can feel confusing, like trying to solve a visual puzzle. Here’s how to approach these paintings:

Start with what you recognize. Even in the most abstract Picasso faces, you can usually identify eyes, nose, and mouth. They might not be in expected positions, but they’re there.

Look for multiple views. Try to identify which parts of the face are shown from the front and which from the side. Picasso often uses color shifts or changes in shading to separate these different perspectives.

Consider the emotion. Despite their abstract nature, Picasso’s portraits are deeply expressive. The angular, sharp forms might suggest tension or conflict, while curved, flowing lines might indicate gentleness or sensuality.

Notice the eyes. Eyes are often the key to understanding a Picasso face. He frequently painted eyes asymmetrically—one closed, one open, or eyes looking in different directions. This wasn’t just formal experimentation; it often represented psychological complexity or seeing things from different perspectives.

Think about the whole composition. Don’t get too caught up in identifying every feature. Step back and consider how the shapes, colors, and lines work together to create an overall impression of a person.

The Influence of African Art on Picasso’s Faces

The impact of African and Oceanic art on Picasso’s development cannot be overstated. In 1907, he visited the Ethnographic Museum at the Palais du Trocadéro in Paris, where he encountered African masks and sculptures. He later described this visit as a revelation that changed his understanding of what art could be.

African masks didn’t try to realistically reproduce human features. Instead, they used abstraction, exaggeration, and symbolism to create powerful spiritual objects. Faces might have elongated features, simplified planes, or symbolic scarification patterns. These masks showed Picasso that a face didn’t need to look “real” to communicate meaning—in fact, abstraction could sometimes communicate more powerfully than realism.

The influence appears clearly in “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” where the two rightmost faces look almost directly inspired by African masks. But the influence went deeper than surface borrowing. African art taught Picasso that facial features could be treated as independent elements to be arranged for expressive and formal purposes, not simply copied from nature.

“African art opened my eyes to how faces could be constructed rather than copied. The mask doesn’t show you what someone looks like—it shows you who they are.”

Pablo Picasso

Picasso’s Techniques for Creating Abstract Faces

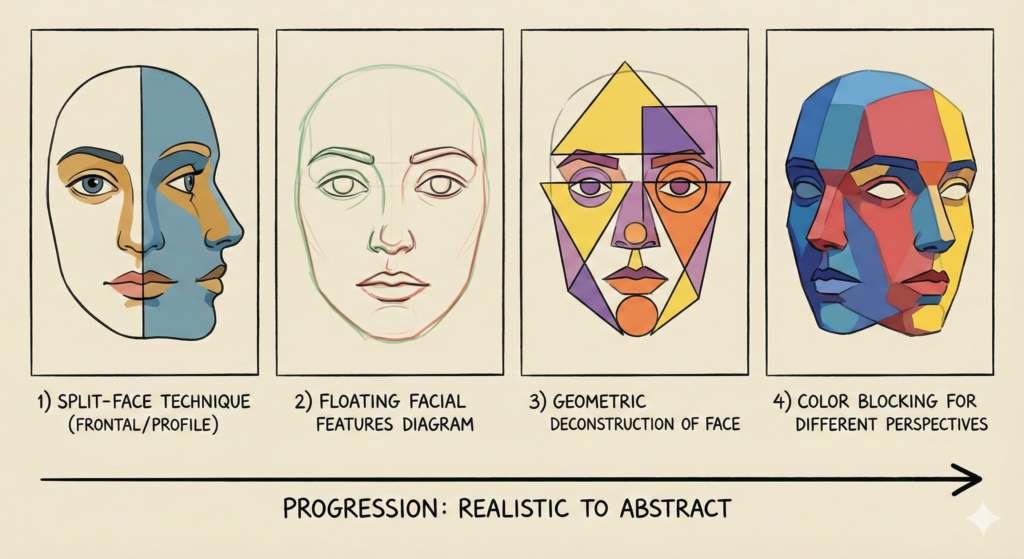

The Split-Face Technique

One of Picasso’s most recognizable methods involved literally splitting a face down the middle and showing each side from different angles. One half might be frontal while the other appears in profile. Sometimes he’d paint the two halves in different colors or styles, representing different aspects of personality or different emotional states.

This technique appears throughout his career, from early Cubist works through his late portraits. The split face became almost a signature for Picasso, instantly recognizable and frequently imitated by other artists.

Floating Features

Picasso often detached facial features from their anatomical moorings, letting eyes, noses, and mouths float independently across the picture plane. An eye might appear near the top of the head while another sits closer to the chin. A nose might migrate to the edge of the face, or a mouth might be shown both smiling and frowning simultaneously.

This wasn’t arbitrary placement. Picasso carefully composed these floating features to create balance and visual interest while maintaining enough connection to facial anatomy that viewers could still recognize what they were seeing.

Color as Structure

While early Analytical Cubism used muted colors to emphasize structure, Picasso’s later abstract faces employed bold, contrasting colors to separate different planes and perspectives. A profile might be painted blue while the frontal view appears yellow, or different emotional states might be represented by different color schemes.

The use of color also helped guide viewers through the complex spatial relationships in his paintings. Warm colors might advance while cool colors recede, creating a shallow, shifting space that couldn’t exist in the real world but felt completely natural in Picasso’s painted universe.

The Psychology Behind Abstract Faces

Picasso wasn’t just playing formal games with his abstract faces—he was exploring psychological truth. Traditional portraits showed the public face, the mask people present to the world. Picasso wanted to show the private self, the contradictions and complexities that exist beneath the surface.

By combining multiple views, he could show how a person appears confident from one angle but vulnerable from another. The split between frontal and profile views might represent the divide between public and private selves, or between conscious and unconscious mind.

His portraits of women, particularly those of his lovers, often revealed his complicated feelings about his relationships. The distortions and fragmentations weren’t just artistic choices—they were psychological insights. A face might be beautiful from one perspective but grotesque from another, suggesting ambivalence or the complexity of human attraction.

Art historians have noted that Picasso’s most abstract and distorted faces often appeared during periods of personal or political turmoil. The “Weeping Woman” series, created during the Spanish Civil War, uses facial distortion to express collective grief and horror at human cruelty. The technique that started as formal experimentation became a powerful tool for emotional expression.

Learning from Picasso: How Artists Today Use Abstract Faces

Picasso’s innovations continue to influence contemporary artists. You can see echoes of his approach in:

- Digital art and graphic design: The simplified, geometric approach to faces that Picasso pioneered appears everywhere in modern logo design and illustration

- Street art and graffiti: Many street artists use Cubist-inspired fragmentation and multiple perspectives

- Comic books and animation: The idea that faces can be simplified to essential shapes while remaining expressive comes directly from Picasso

- Fashion and textile design: Designers frequently reference Picasso’s abstract faces in prints and patterns

Understanding modern art movements requires understanding Picasso’s contribution. His abstract faces didn’t just influence painting—they changed how we visualize the human form across all visual media.

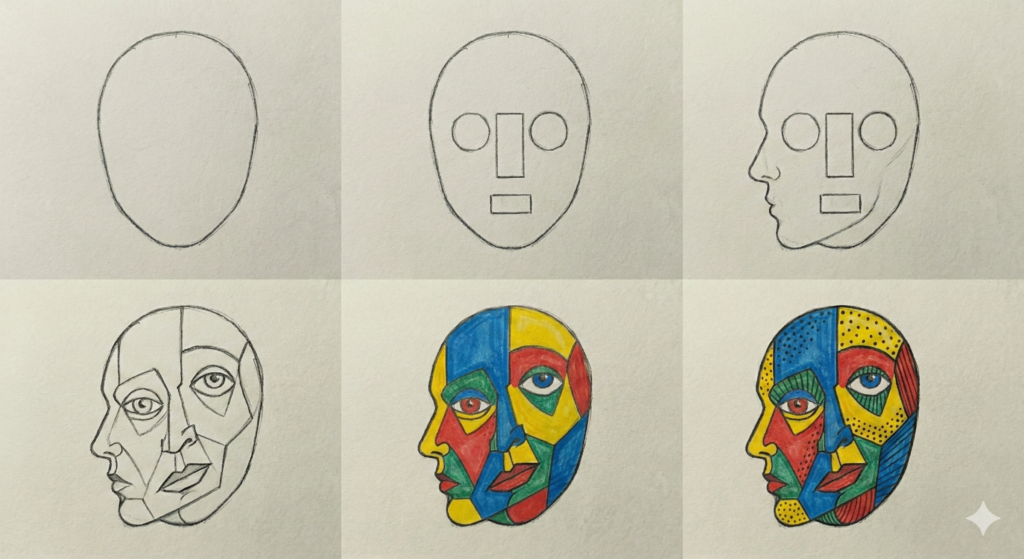

Watch: Drawing Picasso’s Cubist Faces

The Market for Picasso’s Abstract Face Paintings

Picasso’s abstract portraits are among the most valuable paintings in the art market. “Les Femmes d’Alger” (Version O), which includes abstract faces, sold for $179.4 million in 2015, setting a record at the time. Even smaller portraits and studies command millions at auction.

The value reflects not just Picasso’s fame but the historical importance of these works. They represent a crucial turning point in art history when portrait painting broke free from centuries of conventions. Collectors recognize that owning a Picasso abstract face means owning a piece of the revolution that made modern art possible.

Creating Your Own Picasso-Inspired Abstract Face

Want to try painting in Picasso’s style? Here’s a simple approach:

- Start with a basic face outline – Draw or paint a simple oval or geometric shape to represent the head

- Break down the features – Sketch eyes, nose, mouth, and ears as separate geometric shapes rather than realistic forms

- Add a profile view – Incorporate a side view of the nose or one eye in profile while keeping the rest frontal

- Experiment with placement – Move features around—don’t feel bound by anatomical correctness

- Use bold colors – Try using different colors for different facial planes or perspectives

- Add geometric patterns – Incorporate triangles, circles, and angular shapes throughout the composition

- Don’t aim for beauty – Aim for interest, expression, and structural innovation

Remember, Picasso spent years mastering traditional techniques before he broke the rules. Understanding the fundamentals of portrait drawing gives you a stronger foundation for successful abstraction.

Common Misconceptions About Picasso’s Abstract Faces

“Picasso couldn’t paint realistically” This is completely false. Picasso’s early work shows extraordinary skill in realistic drawing and painting. He chose abstraction as a more powerful means of expression, not as a cover for lack of ability.

“The faces are just random and meaningless” While Picasso’s faces may look chaotic, they’re carefully constructed. He made countless sketches and studies, working out the precise placement of every element.

“Anyone could paint like that” Many people have tried to imitate Picasso’s style, but few succeed. His work requires deep understanding of facial structure, composition, and color theory, plus innovative vision to break conventions successfully.

“He was just trying to shock people” While Picasso certainly enjoyed controversy, his abstract faces arose from genuine artistic inquiry about how to represent three-dimensional reality on a two-dimensional surface.

The Legacy of Picasso’s Abstract Faces

Picasso’s revolutionary approach to painting faces changed art forever. Before Picasso, portrait painters felt constrained by rules about proportion, perspective, and realistic representation. After Picasso, artists knew that faces could be deconstructed, reconstructed, and reimagined in countless ways.

His influence extends far beyond fine art. Graphic designers, illustrators, animators, and digital artists all work in a world that Picasso helped create—a world where abstraction and representation can coexist, where a face can be shown from multiple angles simultaneously, and where geometric simplification can create powerful visual communication.

The abstract faces that once shocked and confused viewers in early 20th-century Paris now feel familiar. We’ve absorbed Picasso’s visual language so thoroughly that we barely notice how radical it once was. That’s the mark of truly revolutionary art—it becomes part of how we see.

Today, when we look at a Picasso abstract face, we’re not just seeing paint on canvas. We’re seeing a window into one of the most creative minds in human history, a mind that asked “What if?” and changed everything. Whether you find his faces beautiful, disturbing, or fascinating, you can’t deny their impact. These strange, fractured, multi-viewed portraits opened doors that remain open today, inviting each new generation of artists to see faces—and art itself—in revolutionary new ways.

Understanding Picasso’s artistic legacy means recognizing that his abstract faces weren’t just an artistic style—they were a new visual language that continues to shape how we represent human identity in the 21st century.

Frequently Asked Questions About Picasso’s Abstract Faces

Why did Picasso paint faces from multiple angles? Picasso wanted to show more information about a person than a single viewpoint could capture. By combining frontal, profile, and three-quarter views, he could reveal multiple aspects of a person’s appearance and personality simultaneously. This approach challenged the limitations of traditional perspective that had dominated Western art for centuries.

What inspired Picasso to create abstract faces? Several influences came together: African and Iberian masks showed him that faces could be powerful symbols rather than realistic copies; Paul Cézanne’s geometric approach to composition provided technical foundation; and Picasso’s own desire to innovate beyond traditional portrait painting drove his experimentation. The combination sparked the Cubist revolution.

Are Picasso’s abstract faces Cubism? Yes, his abstract faces are central examples of Cubism, the art movement he co-founded with Georges Braque. Analytical Cubism (1907-1912) featured highly fragmented, monochromatic faces, while Synthetic Cubism (1912-1919) used simpler shapes and brighter colors. Throughout his career, Picasso continued experimenting with Cubist techniques in portraiture.

How do you interpret a Picasso abstract face? Start by identifying recognizable features like eyes, nose, and mouth, even if they’re not in expected positions. Look for multiple perspectives combined in one image—frontal and profile views together. Pay attention to color shifts and geometric patterns that separate different planes. Focus on the overall emotional impression rather than trying to “solve” every element.

What is Picasso’s most famous abstract face painting? “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” (1907) is arguably his most famous, as it launched the Cubist movement. However, “Weeping Woman” (1937) and “Girl Before a Mirror” (1932) are also extremely well-known. His many portraits of lovers and wives throughout his career also rank among his most celebrated works.

Did Picasso always paint abstract faces? No, Picasso’s career spanned over 70 years and included many different styles. His Blue Period and Rose Period featured more realistic faces. Even after developing Cubism, he occasionally returned to more traditional representation. He was constantly experimenting and moving between abstraction and representation throughout his life.

Citations:

- Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). “Pablo Picasso: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79766

- Tate Gallery. “Cubism – Art Term.” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/c/cubism

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).” https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pica/hd_pica.htm

- National Gallery of Art. “Picasso: The Cubist Portraits of Fernande Olivier.” https://www.nga.gov/features/picasso-cubist-portraits.html

- Smithsonian Magazine. “How African Art Influenced the Face of Modern Art.” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-african-art-influenced-face-modern-art-180972639/

- Art Institute of Chicago. “Understanding Picasso’s Weeping Woman.” https://www.artic.edu/articles/756/understanding-picassos-weeping-woman

- Guggenheim Museum. “Pablo Picasso: Analytical Cubism.” https://www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/the-cubist-epoch/analytical-cubism