You know what I love about teaching art history? It’s that moment when a student’s eyes light up – not because they’ve memorized dates and names, but because they’ve actually connected with a painting across centuries. I saw it happen dozens of times during my thirteen years in the classroom, and it’s why I still get excited thinking about places like The Met.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is one of those rare spaces that can do that to you – stop you in your tracks, make you forget about your phone, your to-do list, everything. We’re talking about over two million works of art here, spanning 5,000 years of human creativity. (Yes, you read that right. Two million.) The place is absolutely vast, and honestly? Trying to see everything in one visit is like trying to drink from a fire hose.

That’s exactly why I put this guide together.

Ready to discover what makes these paintings so special? Let’s dive in.

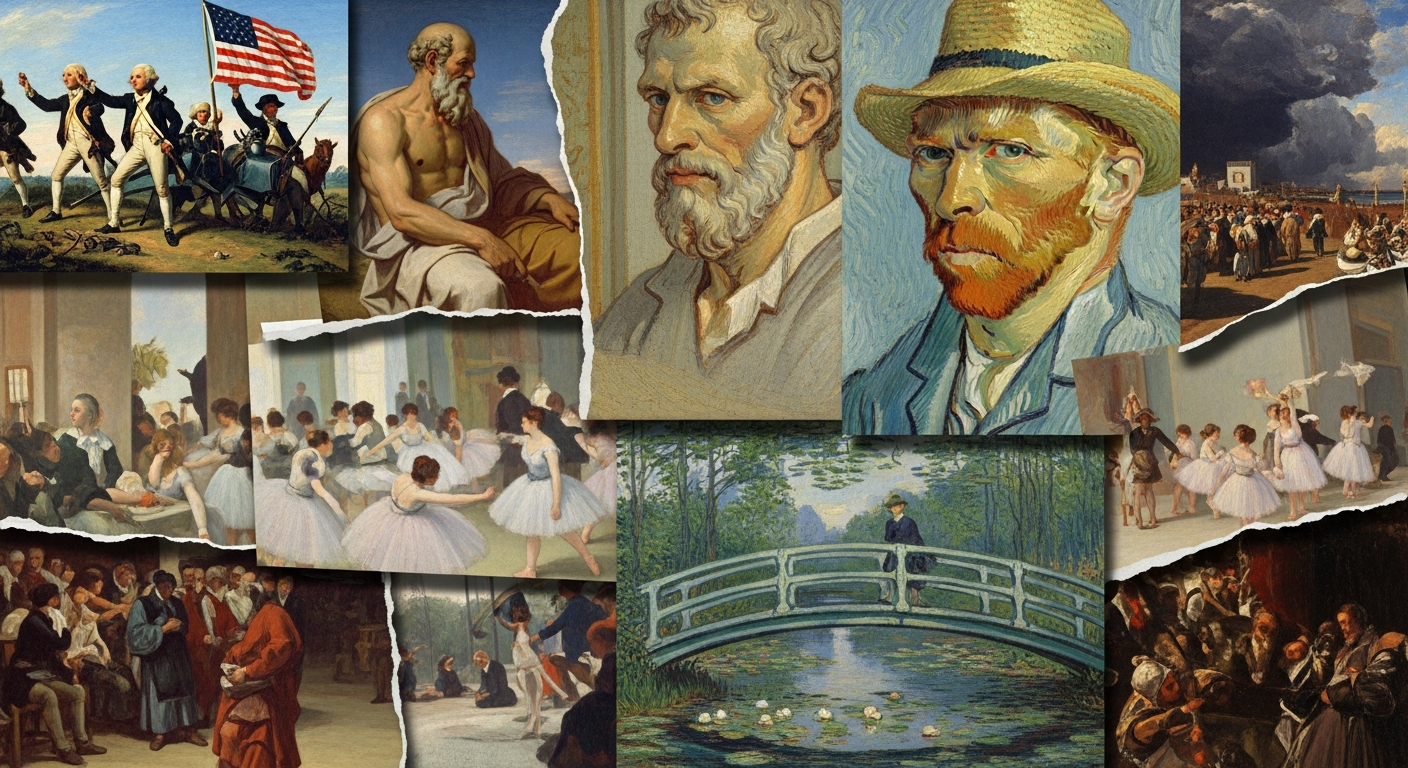

Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) by Emanuel Leutze

Description: This gigantic painting is pure Hollywood-style action. It shows General George Washington on a freezing Christmas night in 1776, leading his troops across the icy Delaware River for a surprise attack. It’s a powerful image of bravery and determination that has become one of the most famous symbols of the American Revolution. The sheer size of the canvas, over 21 feet wide, makes you feel like you’re right there in the boat, shivering along with the soldiers. The first version of this painting was damaged by a fire in Germany and later destroyed in a World War II bombing raid, so Leutze had to paint this masterpiece all over again.

What to Look For: First, notice the light. Leutze uses a dramatic, almost heavenly light to spotlight Washington, making him the clear hero. Look closely at the people in the boat; they represent a cross-section of the young American nation—farmers, soldiers, a Scottish immigrant, and an African American man—all rowing together. Also, check out the ridiculously chunky ice in the river; while maybe not perfectly realistic, it adds to the intense drama of the scene.

Techniques: Leutze used a dramatic, Romantic style of oil painting, focusing on emotion and grandeur rather than perfect historical accuracy. He employed strong compositional lines, with the boat and flag creating a diagonal thrust that gives the scene energy and forward momentum.

Location in Museum: Gallery 760

Estimated Value: Priceless

Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889) by Vincent van Gogh

Description: Get ready for a jolt of energy! Vincent van Gogh painted this electrifying landscape while he was a patient at an asylum in France. You can feel his intense emotions in every brushstroke. The wheat seems to sway, the clouds swirl like whipped cream, and the dark green cypress tree on the left looks like a living flame reaching for the sky. It’s a painting you don’t just see, you feel it. Van Gogh painted this vibrant scene directly from the view he had through the barred window of his room at the asylum.

What to Look For: Zoom in on the paint itself. Van Gogh applied it in thick, paste-like layers called ‘impasto,‘ creating a 3D texture you can almost feel with your eyes. Notice the contrast between the hot yellow of the wheat and the cool blues and greens of the sky and trees. This isn’t just a field; it’s a representation of the powerful forces of nature.

Techniques: This work is a prime example of Post-Impressionism, characterized by Van Gogh’s signature impasto technique. He used thick, visible brushstrokes to convey emotion and movement, creating a deeply personal and expressive landscape.

Location in Museum: Gallery 825

Estimated Value: Priceless

The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David

Description: This painting is like the final, dramatic scene of a movie. It depicts the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, who was sentenced to death for his radical ideas. Instead of begging for his life, he calmly reaches for a cup of poison hemlock while still teaching his devastated followers. It’s a powerful story about standing up for your beliefs, no matter the cost. The artist, Jacques-Louis David, signed his name twice within the painting: once on the bench and once on the block where Plato is seated.

What to Look For: Notice the composition. Socrates is bathed in light, forming a stable, triangular shape, showing his strength and clarity of mind. His followers, on the other hand, are a mess of emotional, curving lines, showing their grief and despair. At the foot of the bed, a man who looks like Plato sits with his back to the scene, lost in thought.

Techniques: David was a master of the Neoclassical style, which was inspired by ancient Greek and Roman art. He used clear, sharp lines, a balanced composition, and dramatic lighting (a technique called chiaroscuro) to create a scene that is both emotionally powerful and morally instructive.

Location in Museum: Gallery 614

Estimated Value: Priceless

Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau) (1883–84) by John Singer Sargent

Description: Meet the original ‘It Girl’ of 1880s Paris. This is a portrait of Virginie Gautreau, a famous socialite known for her beauty and dramatic style. Sargent wanted to create a modern masterpiece, and he did, but it came with a cost. The painting is incredibly elegant and bold, but its confident, almost arrogant, pose and revealing dress caused a massive scandal when it was first shown. The painting was so controversial at the 1884 Paris Salon that Sargent had to repaint one of the dress straps, which he had originally depicted as having slipped off her shoulder.

What to Look For: The most striking feature is the contrast. Look at her ghostly pale skin against the deep black of her dress and the dark background. Her profile is sharp and aristocratic, like a figure on a Roman coin. Also, note the strange, awkward twist of her right arm, a pose that adds to the painting’s tension and artificial elegance.

Techniques: Sargent was a master of oil painting, known for his fluid and confident brushwork. He expertly rendered the different textures, from the soft velvet of the dress to the cool smoothness of Madame Gautreau’s skin, using a limited but powerful color palette.

Location in Museum: Gallery 771

Estimated Value: Priceless

The Harvesters (1565) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Description: This painting is like a time machine back to a hot summer day in the 1500s. It’s not about kings or heroes, but about everyday people. Bruegel shows peasants working hard in the wheat fields, but also taking a much-needed break for lunch under a pear tree. It’s a wonderfully detailed look at rural life, capturing both the toil and the simple joys of the harvest season. This painting is one of only five surviving panels from a famous series of six that depicted different seasons of the year.

What to Look For: The details are everything here. Look for the man fast asleep with his pants unbuttoned, the woman eating porridge, and the tiny figures bathing in a distant pond. Bruegel creates an incredible sense of depth, leading your eye from the workers in the foreground all the way to the ships in the harbor miles away. The golden yellow color of the wheat dominates the scene, making you almost feel the late summer heat.

Techniques: Bruegel was a master of the Northern Renaissance style, using oil on a wood panel. He was renowned for his ‘world landscapes,’ where he combined incredible detail in the foreground with a sweeping, panoramic view that seems to stretch on forever.

Location in Museum: Gallery 642

Estimated Value: Priceless

Young Woman with a Water Pitcher (c. 1662) by Johannes Vermeer

Description: Step into a moment of perfect calm. In this quiet scene, a young woman opens a window to let in the morning light as she holds a shiny water pitcher. Nothing dramatic is happening, but the painting feels incredibly special. Vermeer was a magician with light, and this work is one of his best, capturing a single, peaceful moment in time. Vermeer only produced about 35 known paintings in his entire lifetime, making each one an incredibly rare and precious treasure.

What to Look For: It’s all about the light. Follow the light as it streams in from the leaded-glass window on the left. See how it softly illuminates the woman’s face and white head covering, and how it gleams on the polished brass of the water pitcher and basin. Also, notice the beautiful map on the wall, a common decoration in wealthy Dutch homes of the era.

Techniques: Vermeer was a master of the Dutch Golden Age, known for his meticulous technique and unparalleled ability to paint light. He likely used a ‘camera obscura,’ an early camera-like device, to help him achieve his incredibly realistic depictions of light, shadow, and perspective.

Location in Museum: Gallery 964

Estimated Value: Priceless

Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (1653) by Rembrandt van Rijn

Description: This is a painting about a deep and thoughtful moment. It shows the famous Greek philosopher Aristotle, looking rich and successful, resting his hand on a bust of Homer, a blind poet from centuries before. Aristotle seems to be pondering the difference between his own worldly success and Homer’s timeless artistic genius. It’s a powerful meditation on fame, wisdom, and what truly matters in life. The large gold chain Aristotle wears was a real gift he received from his most famous student, Alexander the Great.

What to Look For: Look for the light and shadow, a technique called ‘chiaroscuro‘ that Rembrandt perfected. The light focuses on three key things: Aristotle’s forehead (symbolizing his mind), his hand (his connection to the past), and the blind eyes of the Homer bust. Also, admire the incredible texture of the fabrics, from the heavy linen sleeve to the gleaming gold chain.

Techniques: Rembrandt was a master of using oil paint to create dramatic light and shadow. His use of chiaroscuro gives the painting a deep, psychological intensity. He applied paint in thick layers to create rich textures that make the clothing and objects seem incredibly real.

Location in Museum: Gallery 964

Estimated Value: Priceless

Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies (1899) by Claude Monet

Description: Welcome to Claude Monet’s personal paradise. This painting shows the famous Japanese-style footbridge in the water garden Monet built at his home in Giverny, France. He wasn’t interested in painting a perfect photo of the bridge; he wanted to capture the feeling of the light, the air, and the reflections on the water. It’s a dreamy, beautiful scene that makes you feel like you’re standing right there with him. Monet was so obsessed with his water garden that he painted this series of water lilies and the Japanese bridge approximately 250 times.

What to Look For: Notice that there’s no sky! Monet focuses entirely on the surface of the pond and the bridge. Look at the thousands of short, quick brushstrokes that make up the water lilies and their reflections. Up close, it might look like a colorful mess, but when you step back, it all blends together to form a shimmering, light-filled image.

Techniques: This is a classic example of Impressionism. Monet used rapid, broken brushstrokes and a vibrant palette to capture the changing effects of light and atmosphere. He often painted the same subject many times at different times of day to study these changes.

Location in Museum: Gallery 819

Estimated Value: Priceless

The Dance Class (1874) by Edgar Degas

Description: This isn’t a glamorous performance; it’s a behind-the-scenes peek at the hard work of being a ballerina. Degas be shows a group of young dancers at the Paris Opéra Ballet, but they aren’t gracefully posing. They’re stretching, adjusting their costumes, and looking exhausted while the ballet master, Jules Perrot, watches over them. It feels like a candid snapshot from real life. The watering can in the foreground was used to sprinkle the dusty wooden floors to prevent the dancers from slipping.

What to Look For: Check out the unusual composition. The scene is framed from a strange, high angle, and the figures on the left are cut off by the edge of the canvas, making it feel like a photograph. Look for the small, personal details: a dancer scratching her back, another adjusting her earring, and a little dog in the foreground.

Techniques: Although associated with the Impressionists, Degas considered himself a Realist. He was a master of drawing and composition. He used oil paints to capture the sense of spontaneous movement and often chose unusual viewpoints to make his scenes feel more immediate and modern.

Location in Museum: Gallery 815

Estimated Value: Priceless

Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (after 1782) by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun

Description: This is a ‘selfie’ from the 1780s, painted by one of the most successful female artists of her time. Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun shows herself not as a stuffy, formal artist, but as a confident, relaxed, and fashionable woman. Holding her palette and brushes, she looks directly at us with a friendly, engaging expression, as if we’ve just interrupted her while she was painting outdoors. She was the official court painter to Queen Marie Antoinette of France, and the two became close friends before the French Revolution.

What to Look For: Notice how she paints herself in a natural, sunlit setting, which was very different from the dark, serious self-portraits male artists usually painted. Look at the incredible detail in the textures, from the silky ribbons on her hat to the delicate lace of her collar. Her direct gaze is key—it shows she is a confident professional in a world dominated by men.

Techniques: Vigée Le Brun worked in a Rococo and Neoclassical style. She was celebrated for her ability to paint flattering and lifelike portraits using smooth, polished brushwork that beautifully captured the luxurious fabrics and fashions of the era.

Location in Museum: Gallery 634

Estimated Value: Priceless

The Collection’s Significance

The Met’s collection is more than just a random assortment of old stuff; it’s a comprehensive library of human creativity. Its incredible breadth, covering virtually every culture and time period, from ancient Egyptian temples to modern American design, makes it unique. Unlike museums that focus on one specific era or style, The Met aims to tell the entire story of art. This encyclopedic approach has made it a global center for art education and inspiration, influencing countless artists, designers, and thinkers. Seeing a Roman statue near a Renaissance painting and a Japanese screen in the next hall shows the universal human drive to create beauty and meaning, connecting us all across time and space.

Final Thoughts

Here’s something I tell every student before their first museum visit: seeing art in person changes you. Standing in front of these masterpieces at The Met – feeling the scale, catching brushstrokes you’d never notice in photos, watching how the paint seems to glow in the gallery light – it’s completely different from any book or screen. Whether you’re a dedicated art lover or just curious, make the trip. You’ll leave inspired, I promise.

Plan Your Visit

Opening Times: Sunday–Tuesday and Thursday: 10 am–5 pm; Friday and Saturday: 10 am–9 pm; Closed Wednesday.

Ticket Prices: Adults: $30; Seniors (65+): $22; Students: $17. Free for Members, Patrons, and children under 12. Booking tickets online in advance is highly recommended.

How to Get There: Subway: 4, 5, or 6 train to 86th Street station. Bus: M1, M2, M3, or M4 bus along Madison or Fifth Avenue.

View on Google Maps / Plan Visit

FAQs about art at Metropolitan Museum of Art

What is the most famous painting at the Met?

While it’s hard to pick just one, ‘Washington Crossing the Delaware’ by Emanuel Leutze is arguably the most famous and recognizable painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection.

Can I take photos of the paintings?

Yes, photography without a flash is permitted in most of the permanent collection galleries for personal use. However, tripods, selfie sticks, and video cameras are not allowed.

How much time should I spend at The Met?

The Met is enormous! To see the highlights on this list and get a good feel for the museum, you should plan to spend at least 3-4 hours. A full day would allow you to explore more collections without rushing.

Is there a museum map?

Yes, you can pick up a free paper map at any information desk inside the museum, or you can view and download a digital map from The Met’s official website before your visit.