As Valentine’s Day approaches, what better way to celebrate love than by exploring how the world’s greatest artists have captured romance on canvas? From tender embraces to passionate kisses, art history offers us a stunning visual archive of human connection that transcends time and culture.

Romance in art isn’t just about pretty pictures of couples holding hands. It’s a complex tapestry woven with threads of desire, death, political revolution, and spiritual transcendence. Each era approached love differently, reflecting the theological doctrines, social norms, and philosophical ideas of its time.

Let’s journey through centuries of romantic masterpieces and discover what makes them timeless expressions of the human heart.

The Sacred Contract: Renaissance Romance

Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait (1434)

Long before Valentine’s cards existed, Jan van Eyck created what many consider the foundational text of domestic romance in Western art. The Arnolfini Portrait depicts Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife in their home, but this is no ordinary portrait.

Every element carries symbolic weight. The single candle burning in the chandelier, despite daylight flooding the room, represents the all-seeing eye of God witnessing their union. The small dog at their feet symbolizes fides—fidelity. Even the discarded wooden clogs suggest they stand on sacred ground.

What makes this painting especially poignant is that it may be a memorial portrait. The carving of Saint Margaret, patron saint of childbirth, combined with historical evidence, suggests van Eyck might have painted this to preserve the memory of Costanza, who may have died in childbirth. If true, it transforms from a legal document into a heartbreaking attempt to arrest time and grant his wife immortality beside him.

The Divine Catastrophe: Baroque Passion

Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (1520-1523)

If van Eyck represents the stillness of the legal bond, Titian’s masterpiece represents the catastrophic, transformative energy of love at first sight.

The painting captures the precise moment when the god Bacchus discovers the abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos. Titian freezes Bacchus mid-air, leaping from his chariot in a precarious, kinetic pose that physically bridges the gap between divine chaos and human isolation. The composition’s diagonal division creates stunning visual tension—the calm, expensive ultramarine sky above representing Ariadne’s future immortality as a constellation, and the riot of earth tones below filled with the god’s chaotic retinue.

This isn’t polite courtship; it’s a divine intervention where grief is instantly supplanted by passion. As noted in technical analysis of the work, Titian creates a masterclass in dynamic tension that perfectly captures the overwhelming nature of sudden, all-consuming love.

Rembrandt’s The Jewish Bride (c. 1665-1669)

Moving into the Dutch Golden Age, Rembrandt van Rijn produced what is arguably the most tender depiction of marital intimacy in the canon.

Unlike the public pageantry of Titian, Rembrandt’s late masterpiece focuses entirely on an internal, private connection. The painting’s psychological core lies in the hands—the man’s hand rests gently on the woman’s breast in a gesture not of possession or lust, but of protection and cherishing. Her hand rises to meet his, pressing it closer to her heart.

Technically, the painting is a tour de force. Rembrandt applied paint with a palette knife, sculpting pigments to create a tactile surface that catches light. He even mixed his white paint with egg or ground glass to build thick ridges, which he glazed with transparent yellows and browns, making the man’s gold sleeve appear to glow from within—radiating warmth that mirrors the emotional temperature of the scene.

This “lightness of physical contact” suggests a relationship defined by deep, silent understanding rather than the frantic energy of new romance. It’s love that has weathered time.

The Theatre of Pleasure: Rococo Romance

Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing (1767)

The 18th century brought a dramatic shift. The Rococo movement treated romance as a sophisticated game—a theater of pleasure where the stakes were social rather than spiritual.

Commissioned by Baron de Saint-Julien, who explicitly requested a painting of his mistress on a swing with himself positioned to look up her dress, The Swing is an unabashed celebration of voyeurism and erotic play. The composition forms a scandalous narrative triangle: an older man pushes the swing, oblivious to the younger lover concealed in the bushes below.

Fragonard’s “foam and foliage” technique creates a lush, overgrown garden that vibrates with energy. The woman’s “billowing, ruffled, ballet-pink dress” against the “celery and avocado green” backdrop creates a visual feast. Unlike the heavy moralizing of the Baroque, The Swing offers a “visual giggle”—capturing the excitement, mischief, and fragility of love that exists solely for the moment.

Revolution in a Kiss: Romanticism and Politics

Francesco Hayez’s The Kiss (1859)

Francesco Hayez’s The Kiss is the quintessential icon of Italian Romanticism, but it’s far more than a medieval love scene—it’s a deeply coded political manifesto.

The man’s foot is placed on a step, his cloak swirls dynamically, suggesting imminent departure. The shadow looming on the left wall implies danger. This is a patriot leaving for battle or exile during the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification.

What’s fascinating is how Hayez used color symbolism to reflect shifting political alliances. In the 1859 version, the woman wears pale blue and the man red—combined with white, these represent the French flag, symbolizing the critical France-Italy alliance against Austria. By 1861, following the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, Hayez painted a version featuring the green-white-red tricolor of the new Italian flag.

The kiss is not merely personal affection; it’s a symbol of national union and love for homeland. The couple’s anonymity allows them to serve as vessels for the viewer’s own patriotic and romantic projections.

The Golden Age: Impressionist Light and Shadow

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Dance in the Country (1883)

Renoir’s approach to romance was fundamentally joyful, devoid of neurotic anxiety. His couples exist in a world of sunlight and social pleasure.

Dance in the Country captures sheer ebullience. The female dancer is Aline Charigot, Renoir’s future wife, and her face is radiant, smiling directly at the viewer with laughing features. The warm, creamy white of her dress and red bonnet contrast against her partner’s dark blue suit. The fluid, rapid brushstrokes at her hem create a “swooshing motion” that mimics the rhythm of the waltz.

The dropped straw hat in the foreground suggests spontaneity—the abandonment of decorum for the joy of the dance. This is romance as celebration, as natural and sunny as the forest light filtering through leaves.

Claude Monet and Camille: Love and Loss

The romantic legacy of Claude Monet is inextricably linked to his first wife, Camille Doncieux. She was the anchor of his early career, appearing in seminal works that document their “unwavering love” amidst poverty and artistic struggle.

The most devastating document of this romance is Camille on Her Deathbed (1879). Monet painted Camille moments after she died, capturing the violet, blue, and grey tones of death encroaching on her face. He later confessed to being tormented by the compulsion to analyze the changing colors even as he grieved—a profound testament to an artist-lover unable to separate his craft from his heart.

Tragically, Monet’s second wife, Alice Hoschedé, consumed by jealousy of her “departed rival,” destroyed almost all photographic records of Camille. Consequently, Monet’s paintings remain the only surviving evidence of her existence, turning his oeuvre into a defiant archive of his first love.

The Sacred and the Anxious: Two Kisses

Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1907-1908)

Klimt’s The Kiss is perhaps the most universally recognized image of romance. The couple kneels at the edge of a flowery meadow that abruptly ends—they’re perched on a precipice, suggesting their love exists in a precarious, separate reality.

Klimt applies gold leaf directly to the canvas, a technique inspired by Byzantine mosaics. This sacralizes the lovers, turning them into a modern icon existing outside time and space. The clothing serves as gender symbolism: the man’s robe features rigid, rectangular shapes while the woman’s dress displays soft, circular patterns. In their embrace, these opposites merge into a single, golden monolith.

It’s a portrayal of love as a spiritual event, a “devotion rendered in gold leaf.”

Edvard Munch’s The Kiss (1897)

If Klimt’s fusion is ecstatic, Munch’s is existential. The most striking feature is the absence of individual identities—the faces of the lovers melt into one another, forming a single, abstract shape. For Munch, this represents the “battle between men and women that is called love”—the terrifying realization that true intimacy involves a loss of individuality.

Unlike Klimt’s gold, Munch uses dark, moody tones. It’s a visual representation of the anxiety that accompanies total surrender to another person.

Modern Love: From Euphoria to Mystery

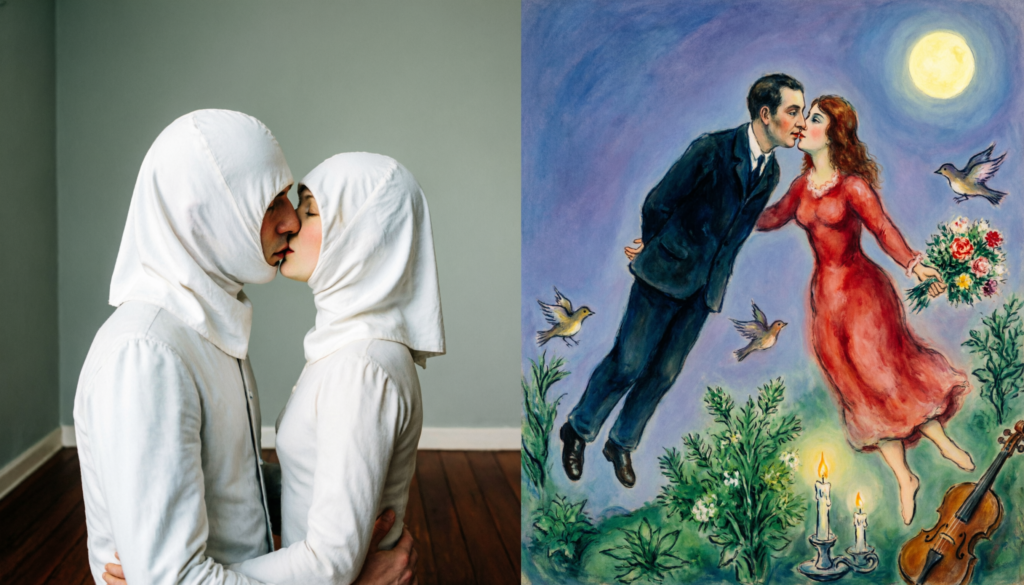

Marc Chagall’s The Birthday (1915)

Painted weeks before his marriage to Bella Rosenfeld, The Birthday is pure domestic joy. Overcome with love, Chagall depicts himself floating impossibly above Bella, twisting his neck to kiss her.

Chagall rejected physics for emotion. “Love and fantasy go hand in hand,” he stated. The floating signifies elation—being “light on one’s feet” taken to its literal extreme. Bella remained Chagall’s primary muse throughout his life; in his memoir, he wrote, “Her silence is mine, her eyes mine.”

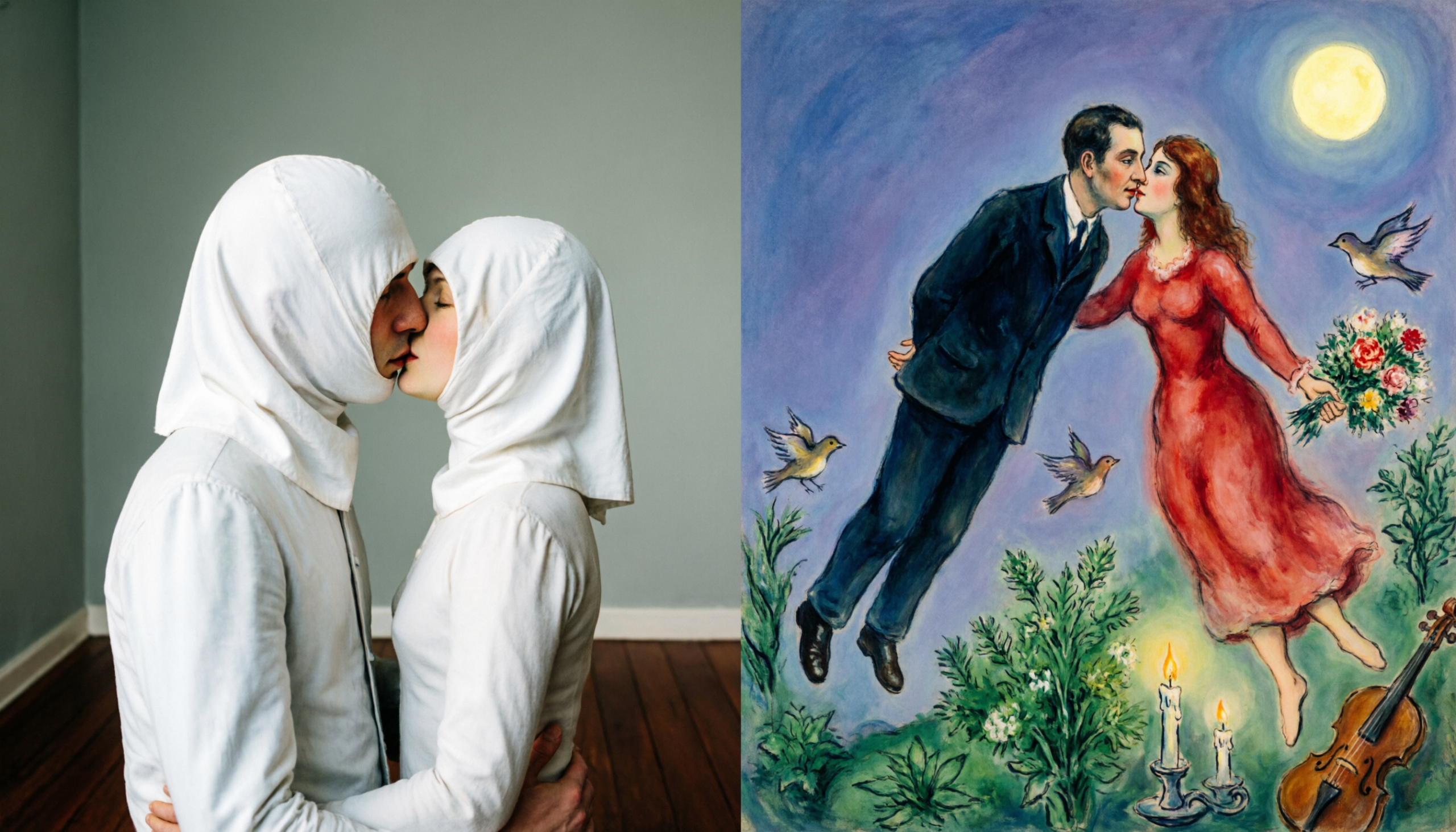

René Magritte’s The Lovers (1928)

Magritte’s The Lovers presents a stark contrast. Two figures attempt to kiss, but their heads are entirely wrapped in white cloth.

The cloth acts as a barrier, transforming passion into frustration and isolation. It suggests we can never truly know our lovers; there’s always a veil preventing total connection. Some link the shrouds to the suicide of Magritte’s mother, who drowned and was found with her nightgown wrapped around her face—connecting intimacy with death and trauma.

What Makes These Paintings Timeless?

The history of romantic painting reveals three core insights:

First, love is a chameleon. In The Arnolfini Portrait, love is legal solidity. In Hayez’s Kiss, it’s a political weapon. In The Swing, it’s rebellious play. The “most romantic” painting depends entirely on what we need love to be: safety, danger, revolution, or escape.

Second, obstruction intensifies romance. The wall in The Black Brunswicker, the cloth in The Lovers, the impending departure in Romeo and Juliet—art suggests that romance is most visible when threatened by war, society, or time itself.

Third, the most enduring romantic paintings are autobiographical. Monet painting Camille, Chagall painting Bella, Renoir painting Aline. These works transcend style because they possess the weight of lived reality. They’re not just allegories of “Love” but specific, desperate attempts to preserve a beloved face from the erasure of death.

Conclusion: Love Never Goes Out of Style

From the golden void of Klimt to the rainy elegance of contemporary works, these paintings prove that while definitions of romance change, the human impulse to capture it in pigment and oil remains one of the most powerful drives in creative history.

This Valentine’s Day, whether you’re celebrating with a partner, honoring a lost love, or simply appreciating the beauty of human connection, remember that artists have been painting our deepest feelings for centuries. Their canvases remind us that love—in all its forms—is worth preserving, worth celebrating, and always worth fighting for.

Citations:

- National Gallery. “Highlights from the collection.” Available at: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/must-sees

- The Wallace Collection. “Paintings.” Available at: https://www.wallacecollection.org/explore/collection/paintings/

- Art Renewal Center. “The Story of Springtime by Fred Ross.” Available at: https://www.artrenewal.org/Article/Title/the-story-of-springtime

- DailyArt Magazine. “An Ode to the Kiss in Art.” Available at: https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/an-ode-to-the-kiss-in-art/

- My Daily Art Display. “Camille Doncieux and Claude Monet.” Available at: https://mydailyartdisplay.uk/2012/01/30/camille-doncieux-and-claude-monet/