Have you ever walked through a modern art museum, stopped in front of a piece that looked like… well, not much at all, and wondered, “Wait, is this really art?” Maybe it was just a pile of rocks, some scribbled text on a wall, or even an empty room. You’re not alone in feeling puzzled. Conceptual art has been confusing and frustrating people since the 1960s, when artists started claiming that the idea behind the artwork mattered more than how pretty or skillful it looked.

But here’s the real question that gets everyone talking: Is conceptual art just ideas floating around in someone’s head? The answer is way more interesting than you might think. Conceptual art transforms abstract thoughts into tangible expressions that challenge how we think about creativity, skill, and what counts as “real” art in the first place.

Learn About

- Conceptual art prioritizes the idea or concept over traditional aesthetic beauty

- Artists use diverse materials and methods to manifest their ideas physically

- The viewer’s participation and interpretation complete the artwork

- Conceptual art emerged in the 1960s as a rebellion against traditional art forms

- It has fundamentally changed contemporary art and how we define artistic value

What Is Conceptual Art, Really?

Let’s start with the basics. Conceptual art is an art movement where the idea or concept behind the work is more important than the finished product itself. Think of it like this: in traditional painting, you might admire the artist’s brushwork, color choices, or realistic rendering. In conceptual art, you’re supposed to engage with the thinking behind the piece—even if it doesn’t look impressive at first glance.

This movement exploded in the 1960s when artists got tired of the art world’s obsession with pretty objects that rich people could hang on their walls. They wanted art to be about big ideas, social commentary, and philosophical questions rather than just decoration.

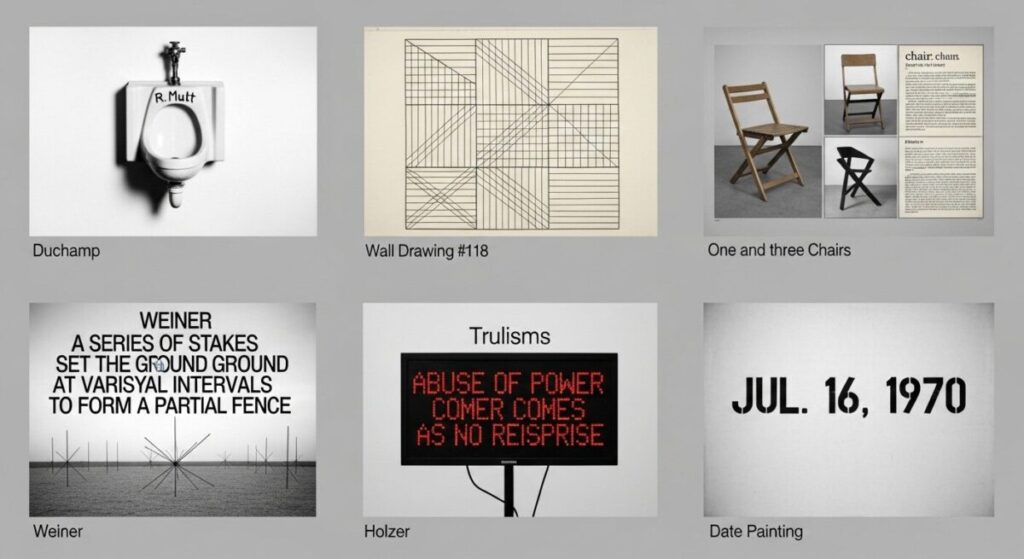

The Game-Changer: Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain

The grandfather of conceptual art was Marcel Duchamp, who shocked everyone in 1917 when he submitted a urinal he had purchased, turned it on its side, placed it on a pedestal, signed it “R. Mutt 1917” and named it Fountain. The art world lost its mind. Was he serious? Was this a joke?

That was exactly the point. Duchamp wanted people to question: “What makes something art? Is it the skill involved? The materials? Or could it be that simply choosing and presenting an ordinary object as art is itself a creative act?”

How Do Conceptual Artists Make Their Ideas Tangible?

Here’s where things get really interesting. If conceptual art is about ideas, how do artists actually show those ideas to the world? After all, you can’t just hang a thought on a museum wall. Let’s break down the creative process.

The Idea as a Blueprint

Every conceptual artwork starts with a question, observation, or commentary about the world. Artists spend months or even years researching, thinking, and refining their core concepts. They might explore:

- Philosophical questions about existence and perception

- Social and political issues like inequality or power structures

- The nature of art itself and who gets to decide what’s valuable

- Human relationships and communication

This intellectual work is just as important—maybe more important—than any physical skill involved in making the piece.

Choosing Materials That Match the Message

One of the coolest things about conceptual art is how artists pick their materials. Unlike traditional painters who stick to canvas and oils, conceptual artists use whatever best serves their idea:

| Material Type | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Found Objects | Challenge notions of value and originality | Duchamp’s everyday items |

| The Artist’s Body | Make art ephemeral and experiential | Performance art |

| Text and Language | Communicate directly with viewers | Instructions, manifestos |

| Empty Space | Question what’s missing or invisible | Minimal installations |

| Social Interactions | Make relationships the artwork | Participatory projects |

The choice isn’t random—it’s strategic. If an artist wants to talk about consumerism, they might use actual trash or product packaging. If they’re exploring memory, they might create something that disappears or changes over time.

Beyond Pretty Pictures: Forms of Tangible Conceptual Art

Conceptual art shows up in way more formats than you might expect. Let’s explore the main types you’ll encounter in museums and galleries.

Performance Art: The Body as Medium

Performance art is when the artist’s own body becomes the artwork. Marina Abramović, who calls herself the “grandmother of performance art,” explores body art, endurance, the relationship between performer and audience, and the limits of the body. In one famous piece called Rhythm 0, she stood still for six hours while audience members could do anything they wanted to her using 72 objects she provided—including roses, perfume, a loaded gun, and scissors.

The “tangible” part? The intense emotional experience, the documentation (photos and videos), and the conversations and memories that lasted long after the performance ended. You can read more about performance art’s evolution to understand its broader impact on contemporary art.

Installation Art: Ideas You Can Walk Through

Installation art creates entire environments where visitors experience the concept spatially. Artist Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (2003) at London’s Tate Modern filled a massive hall with artificial sunlight and mist. People could walk through, lie down, and feel like they were inside the sun itself. The idea? To make viewers think about nature, artificial environments, and how we perceive light and space.

Text-Based Art: When Words Are the Canvas

Some conceptual artists skip images entirely and use words as their medium. Artists like Jenny Holzer project provocative statements onto buildings, making passersby confront uncomfortable truths about power, violence, and society. These aren’t just pretty typography—they’re carefully crafted messages designed to unsettle and enlighten.

“In conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair.”

Sol LeWitt, artist and writer

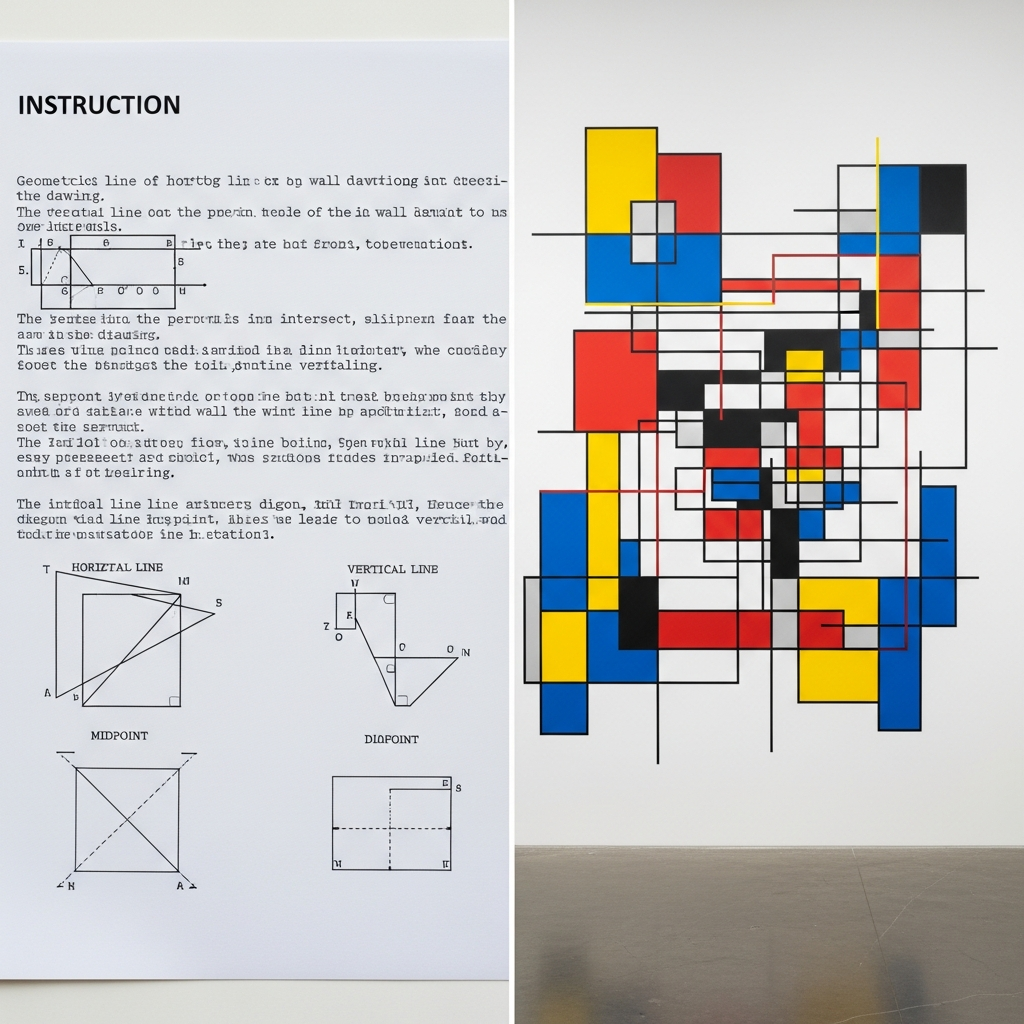

Instruction-Based Art: Art That Lives in Your Mind

This is where things get really wild. Some conceptual artworks are just instructions. Sol LeWitt created wall drawings that consisted only of written directions for how to create geometric patterns. Other people—assistants, museum staff, future artists—would follow the instructions to make the actual drawing.

Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit (1964) is a book of instruction pieces like “Draw a map to get lost.” The artwork exists whether you actually do the instruction or just imagine it in your head. Mind-blowing, right?

[Image placeholder: Example of Sol LeWitt wall drawing instructions next to completed work]

Relational Aesthetics: People Are the Art

In the 1990s, artist Rirkrit Tiravanija literally cooked pad thai and served it to gallery visitors. That was the art—people eating, talking, and connecting. The tangible expressions were the shared meal, the relationships formed, and the social experience that challenged what a gallery visit should be.

Your Brain Completes the Picture: The Viewer’s Role

Here’s something crucial that separates conceptual art from traditional art: you, the viewer, are essential to making the artwork “work.”

Traditional art can exist and be beautiful whether anyone looks at it or not. But conceptual art needs your intellectual participation. When you read the instructions, question the meaning, feel confused or angry or enlightened—that’s when the art becomes complete.

Think about Duchamp’s urinal again. If everyone just said “cool bathroom fixture” and walked away, the piece would have failed. But because people engaged with the idea—arguing whether it was art, questioning artistic authority, debating craftsmanship versus concept—the artwork succeeded brilliantly.

This is why understanding abstract art requires a shift in how we approach looking at art. We’re not just passive observers; we’re active participants in creating meaning.

“But My Kid Could Make That!” Addressing the Skeptics

Let’s tackle the elephant in the room. The most common criticism of conceptual art sounds like this: “That’s lazy!” “Where’s the skill?” “A five-year-old could do that!”

These criticisms miss the point entirely, but they’re worth addressing:

It’s Not About Technical Skill—It’s About Intellectual Rigor

Creating good conceptual art requires:

- Deep research and critical thinking

- Understanding art history and theory

- Strategic decision-making about materials and presentation

- Clear communication of complex ideas

- Courage to challenge established norms

Just because it doesn’t require paintbrush skills doesn’t mean it’s easy. Try coming up with an original idea that makes thousands of people reconsider their entire understanding of art. Not so simple anymore, is it?

It Has Profoundly Shaped Contemporary Art

Whether you love it or hate it, conceptual art has fundamentally changed the art world. It opened doors for:

- Installation art

- Performance art

- Video and digital art

- Participatory and interactive art

- Social practice art

Today’s most exciting contemporary artists build on conceptual art’s foundations, even if they incorporate traditional skills too.

It Makes Us Think Differently About Value

Conceptual art forces uncomfortable questions: Why is a Rembrandt worth millions? Because of the skill? The beauty? The rarity? The artist’s reputation? Or because we collectively decided it has value?

These questions might seem annoying, but they’re actually incredibly important for understanding how society creates meaning, power, and worth—not just in art, but in everything.

Famous Conceptual Art Examples That Changed Everything

Let’s look at some landmark pieces that show how ideas become tangible:

Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965)

This piece shows a physical chair, a photograph of that chair, and a dictionary definition of “chair.” It asks: Which is the “real” chair? The object? The image? The concept? This simple arrangement makes you question representation, language, and reality itself.

Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964)

Ono sat motionless while audience members took turns cutting off pieces of her clothing. The tangible elements? The vulnerability, the gender dynamics, the tension in the room, and the conversations about consent and power that continue today.

Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2010)

The artist filled Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall with 100 million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds. Visitors could walk on them (initially). It looked like a sea of seeds but represented mass production, Chinese labor, and individual identity within massive populations.

You can explore more about modern art movements to see how conceptual art fits into the broader evolution of contemporary creativity.

How to Actually “Get” Conceptual Art

If you’re still feeling confused when you encounter conceptual art, here are some practical strategies:

- Read the wall text or artist statement – Unlike traditional art where you can just look and enjoy, conceptual art usually needs context

- Ask questions – What is the artist trying to communicate? Why did they choose these materials? What am I supposed to feel?

- Consider the historical context – When was this made? What was happening in the world at that time?

- Engage honestly – If you hate it, think about why you hate it. That emotional response might be exactly what the artist wanted

- Give it time – Some conceptual pieces reveal their meaning slowly, not instantly

The Lasting Impact: Why Conceptual Art Still Matters

Conceptual art isn’t going anywhere. In our digital age, where ideas can spread instantly, where NFTs sell for millions, where social media makes everyone a curator of their own brand—conceptual art’s principles are more relevant than ever.

The movement taught us that:

- Art can be a vehicle for social change and critical discourse

- Traditional hierarchies about what “counts” as art are worth questioning

- The conversation around art can be as important as the object itself

- Intellectual engagement is a valid form of aesthetic experience

Whether you love conceptual art or find it frustrating, there’s no denying its impact on how we think about creativity, value, and expression in the 21st century. You can explore related movements like minimalism and postmodern art to see how these ideas evolved.

Conclusion: Ideas Made Real

So, is conceptual art just ideas? Not at all. It’s ideas transformed into experiences, objects, performances, environments, and provocations that change how we see the world. The tangible expressions might look different from a traditional painting—they might be a performance that disappears, instructions you carry in your head, or an empty room that makes you question space itself—but they’re absolutely real.

Conceptual art challenges us to expand our definition of what art can be and do. It demands that we think, question, and participate rather than just admire from a distance. And in doing so, it proves that the most powerful artistic expressions often live at the intersection of thought and action, idea and manifestation, concept and reality.

The next time you encounter a piece of conceptual art that makes you scratch your head, don’t just walk away frustrated. Stop. Think. Ask questions. You might just find that the “idea” is more tangible than you ever imagined.

FAQ: Common Questions About Conceptual Art

Is conceptual art solely about the idea?

No, conceptual art isn’t solely about the idea—it’s about how that idea is manifested and experienced. While the concept is the most important element, the execution, materials, documentation, and viewer engagement are all crucial tangible components that make the artwork complete and impactful.

What is the core principle of conceptual art?

The core principle of conceptual art is that the idea or concept behind the artwork is more important than its aesthetic appearance or the traditional technical skill involved in creating it. This principle emerged in the 1960s as artists challenged formalist approaches and questioned what defines art itself.

How do conceptual artists make their ideas tangible?

Conceptual artists transform abstract ideas into tangible expressions through various methods including performance art, installation art, text-based works, instruction pieces, documentation (photos/videos), found objects, and participatory experiences that engage viewers directly. The “tangibility” often exists in the experience, conversation, or intellectual engagement rather than just physical objects.

Why is conceptual art considered art?

Conceptual art is considered art because it fulfills art’s fundamental purpose: to communicate ideas, provoke thought, challenge perceptions, and create meaningful experiences. Just as poetry doesn’t need to rhyme to be poetry, art doesn’t need traditional aesthetic beauty or technical skill to be art—it needs to engage with human experience and cultural discourse.

What defines a successful conceptual artwork?

A successful conceptual artwork effectively communicates its core idea, provokes meaningful engagement from viewers, generates discussion and interpretation, challenges existing assumptions about art or society, and creates a lasting impact through documentation, memory, or cultural influence. Success isn’t measured by aesthetic beauty but by intellectual and experiential resonance.

Can anyone create conceptual art?

Technically anyone can attempt conceptual art, but creating meaningful conceptual art requires deep knowledge of art history, philosophical inquiry, critical thinking, strategic material choices, and the ability to articulate complex ideas effectively. The intellectual rigor and research involved are just as demanding as traditional artistic skills.

How is conceptual art different from abstract art?

While abstract art focuses on visual elements like color, form, and composition rather than realistic representation, conceptual art prioritizes the idea or concept over all visual concerns. Abstract art can still be about aesthetic beauty and technical skill, while conceptual art may intentionally reject both in favor of intellectual engagement.

Additional Resources

- Tate Museum: Art Terms – Conceptual Art – Comprehensive overview from one of the world’s leading modern art institutions

- MoMA Learning: Conceptual Art – Educational resources and examples from the Museum of Modern Art

- The Art Story: Conceptual Art – Detailed history, key artists, and major works

- Smarthistory: Introduction to Conceptual Art – Free art history resources with expert analysis

- Philadelphia Museum of Art: Marcel Duchamp Collection – Extensive collection of the conceptual art pioneer’s work

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: The Definition of Art – Philosophical perspectives on defining art