Guide to Surrealism Art: Imagine a world where clocks melt on sun-drenched beaches and elephants stand on impossibly long, spindly legs. This is the world of Surrealism, a profound art movement that sought to unlock the power of the unconscious mind. Emerging in the 1920s in Paris from the ashes of Dada, a nihilistic anti-art movement, it was led by the charismatic writer André Breton. The Surrealists believed that the true wellspring of creativity lay not in the rational, logical world, but in the realm of dreams and the irrational.

The group was deeply influenced by the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud, who argued that dreams were a window into our deepest desires and fears. The fundamental goal of surrealism was to free art from the confines of logic and reason, tapping directly into this mysterious and often bizarre world of dreams. This comprehensive article will serve as your definitive guide to this fascinating and influential movement, exploring its origins, core principles, diverse styles, key figures, and its lasting impact on art and culture across the globe.

Keypoints Summary

- Origin: The Surrealist movement began in Paris in the 1920s, growing out of the earlier Dada movement.

- Core Idea: Surrealism sought to liberate the creative potential of the unconscious mind.

- Influence: The movement was heavily influenced by the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud, especially his work on dream analysis.

- Goal: The primary goal was to resolve the conflict between dream and reality into a new “super-reality” or surreality.

- Techniques: Artists used methods like psychic automatism to bypass rational thought and access their subconscious.

The Core Principles and Surrealism Art Ideas

The central tenet of surrealism is the belief that the subconscious mind holds the key to a deeper reality, one that is more profound and authentic than what we experience in our waking lives. The movement’s founders, led by André Breton, were deeply disillusioned by the rational, logical world that had led to the horrors of World War I. They turned to the work of Sigmund Freud, arguing that the true, uncorrupted essence of humanity resided in the primal drives and desires of the unconscious.

To access this inner world, artists embraced a revolutionary method to bypass rational thought, a technique they called psychic automatism. This was not merely a style, but a complete philosophy of creation, demanding spontaneous and uninhibited output where the hand would move without the mind’s conscious direction. Artists would engage in automatic writing or drawing, allowing their unconscious impulses to flow freely onto the page without a pre-conceived plan or self-censorship. This process was a vital tool for tapping into the wellspring of dreams and subconscious imagery.

From this core idea, a wealth of surrealism art ideas emerged, manifesting in a diverse range of forms. The common themes were a direct reflection of this fascination with the hidden self, including dreams, fantasy, the subconscious, and, most powerfully, the uncanny juxtaposition of unrelated objects. Artists sought to create a “super-reality” where the logic of waking life was suspended. For example, in Salvador Dalí‘s iconic “The Persistence of Memory,” a familiar pocket watch becomes a soft, melting form, draping over a tree branch and the edge of a table in a desolate landscape. The eerie, hyper-realistic rendering of these impossible objects creates a profound sense of wonder and discomfort, forcing the viewer to confront a world where the rules of time and matter have been dissolved. This distortion of a familiar object is a signature technique, creating a powerful emotional resonance by making the normal feel deeply strange.

Other key principles involved:

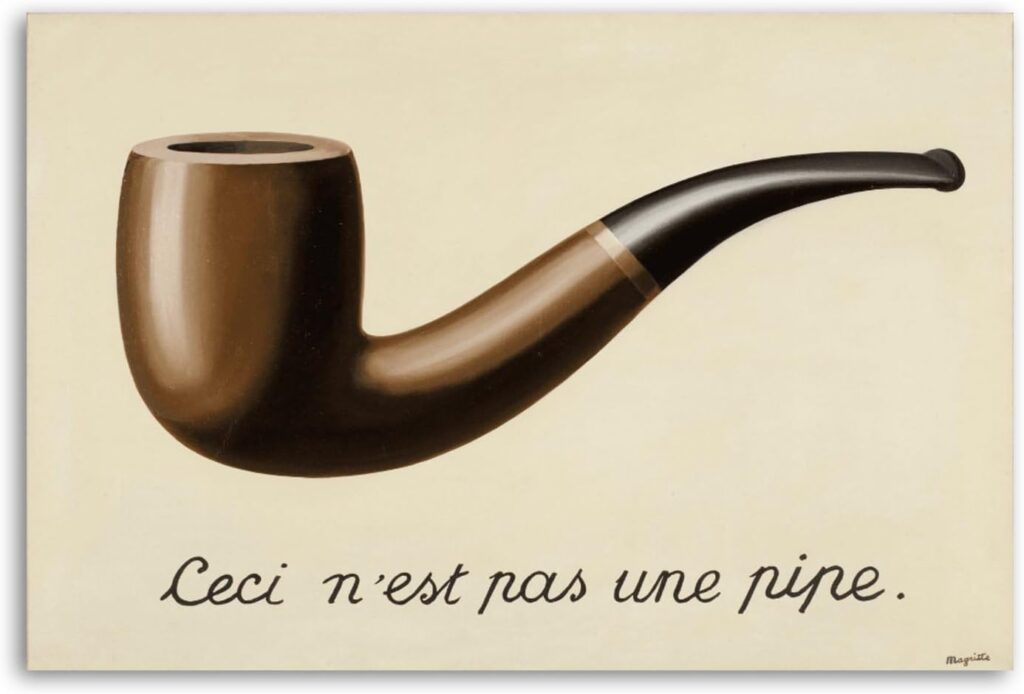

- Juxtaposition: This technique involves placing two or more unconnected or contradictory objects together to create a new, surprising image. The unexpected combination of elements forces the viewer to forge a new meaning, often one that is emotionally resonant or unsettling. A classic example is René Magritte‘s “The Treachery of Images,” which depicts a realistic pipe but is captioned, “This is not a pipe.” This simple juxtaposition of image and text challenges our very perception of reality. This is a foundational technique you’ll see in countless pictures of surrealism art.

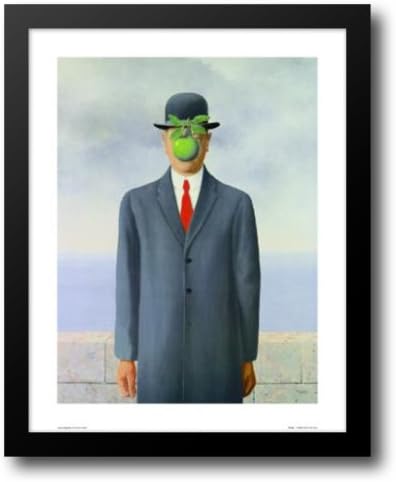

- The Uncanny: The uncanny is that deeply unsettling feeling you get when something familiar suddenly becomes strange and foreign. Magritte’s “The Son of Man,” which features a man’s face obscured by a floating green apple, is a prime example. The image is familiar yet deeply unsettling, forcing the viewer to confront a disturbing psychological paradox.

- Symbolism: Surrealists employed a rich language of symbols from dreams, mythology, and their personal lives to convey a deeper, often cryptic, meaning. These symbols were not always universal; they could be deeply personal and require the viewer to engage with the work on an intuitive level. For example, the recurring motif of the elephant with long, spindly legs in Dalí’s work is a symbol of a dreamlike absurdity and the weight of existence, untethered from reality.

Surrealism Art for Beginners: Getting Started with Easy Surrealism Artwork

If the world of surrealism seems intimidating, don’t worry—it’s an incredibly accessible style for new artists. The essence of surrealism is to let go of rules, silence your inner critic, and embrace the unexpected. For surrealism art for beginners, the best approach is to start with simple exercises that force you to abandon your conscious control. One of the most effective techniques is the “exquisite corpse,” a collaborative drawing game where each person adds to a drawing without seeing the previous person’s work. The resulting fragmented and unpredictable image is a perfect entry point into surrealist thinking.

Another great way to create easy surrealism artwork is to use a familiar scene as a starting point and add a single, surprising element. For example, draw a realistic landscape and then place a giant, floating teacup in the sky, casting a shadow that makes no sense. Or, take a self-portrait and replace one of your eyes with a moon, or your nose with a small, flowering tree. The key is to embrace intuition and not overthink the final result. You can experiment with different mediums, from drawing and painting to collage, which is perfect for cutting and pasting disparate images to create bizarre new compositions.

Diverse Styles: From Abstract Surrealism to Pop Surrealism Art

While Salvador Dalí’s meticulously rendered dreamscapes and René Magritte’s witty, unsettling tableaux often define the public’s perception of the movement, surrealism is a diverse field with many different visual expressions. One major branch is abstract surrealism, which focused more on symbolic, non-representational forms rather than recognizable objects. Artists like Joan Miró and André Masson explored automatism through fluid lines and biomorphic shapes that seemed to emerge from the subconscious. This style is less about depicting a dream and more about visualizing the process of dreaming itself—the free-flowing associations and uninhibited emotional currents that define our inner world. They sought to capture the raw, unedited energy of the subconscious.

Later, the surrealist impulse continued to evolve and spread. Pop surrealism art, also known as Lowbrow, emerged in the late 20th century, particularly in Southern California. It blended the dreamlike imagery of surrealism with elements of pop culture, street art, and comic books. While not officially part of the original surrealist movement, its focus on fantastic, often whimsical, and emotionally charged narratives makes it a direct descendant of the original spirit. This style is often highly detailed, colorful, and playful, yet it retains a surrealist’s fascination with the strange and the unconventional. Artists like Mark Ryden and Todd Schorr are masters of this style, creating narrative paintings that are both deeply unsettling and aesthetically captivating.

Thematic Explorations: Animal Surrealism Art, Landscape Surrealism and More

Surrealism’s flexibility allowed artists to apply its principles to virtually any subject matter. Animal surrealism art is a captivating subgenre where artists often distort, combine, or anthropomorphize creatures to explore themes of nature, instinct, and the wild side of the human psyche. The work of artists like Max Ernst is a prime example. He often used techniques like frottage (rubbing a drawing surface over a textured object) and grattage (scraping paint off a canvas) to create fantastical creatures and landscapes that seemed to be born from pure accident. In his work, a lion might have a fish’s tail or a bird’s feathers, creating a hybrid that is both familiar and alien.

Similarly, landscape surrealism transforms familiar scenery into alien worlds, often with a profound psychological undertone. These paintings often ground the viewer in reality with their composition, only to disorient them with impossible features—floating rocks, empty skies, and bizarre structures that defy the laws of physics. Artists like Yves Tanguy used vast, featureless spaces to create a sense of infinite, introspective emptiness, while Salvador Dalí’s landscapes are famous for their eerie, hyper-realistic detail and unsettling stillness, creating a sense of suspended time. These surrealist takes on landscapes can be found in countless surrealism art pictures.

Key Figures in the Movement: Picasso and Surrealism, Surrealism and Women

Surrealism was an influential art movement that emerged in the 1920s, seeking to unleash the power of the unconscious mind and explore the realm of dreams and irrationality. Here’s a table of some of the most important Surrealist artists and their key contributions:

| Artist | Nationality | Key Contributions & Style | Famous Works |

| Salvador Dalí | Spanish | Perhaps the most iconic Surrealist, known for his meticulously detailed, hallucinatory, and dream-like paintings. He developed the “paranoiac-critical method” to tap into his subconscious. His work often features distorted objects, barren landscapes, and Freudian symbolism. | The Persistence of Memory (1931), The Elephants (1948), Swans Reflecting Elephants (1937) |

| René Magritte | Belgian | Known for his witty and thought-provoking paintings that challenge perception and the relationship between reality and illusion. He often depicted everyday objects in unexpected or unsettling contexts, playing with visual puns and philosophical concepts. | The Treachery of Images (Ceci n’est pas une pipe) (1929), The Son of Man (1964), Golconda (1953) |

| Max Ernst | German | A versatile artist who experimented with various techniques like frottage (rubbing), grattage (scraping), and collage to create unsettling, dreamlike imagery. His work often features fantastical creatures, bizarre landscapes, and themes of myth and the subconscious. | The Elephant Celebes (1921), Europe After the Rain II (1940-42), The Robing of the Bride (1940) |

| Joan Miró | Spanish | Developed a unique, biomorphic and abstract style influenced by childhood imagination and Catalan folklore. His works are characterized by vibrant colors, playful shapes, and a sense of liberation from traditional artistic conventions. He often used automatic drawing techniques. | The Tilled Field (1923-24), Harlequin’s Carnival (1924-25), The Hunter (Catalan Landscape) (1923-24) |

| Frida Kahlo | Mexican | While often associated with Surrealism (André Breton described her as such), Kahlo herself stated she painted her reality, not dreams. Her intensely personal and autobiographical self-portraits are rich in symbolism, drawing heavily from Mexican culture and exploring themes of pain, identity, and resilience. | The Two Fridas (1939), The Broken Column (1944), Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940) |

| Man Ray | American | Primarily known for his photography, he played a crucial role in both Dada and Surrealism. He manipulated photographs to create strange compositions, utilizing techniques like solarization and “rayographs” (cameraless photographs). He also created paintings, objects, and films. | Ingres’s Violin (1924), Glass Tears (1932), Le Violon d’Ingres (1924) |

| Leonora Carrington | British/Mexican | A prolific painter and writer, her work often features fantastical beasts, mythical narratives, and allegories drawing from folklore, alchemy, and her own dreams. She explored themes of transformation, identity, and the liberation of the female spirit. | Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) (1937-38), The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg) (1947), Are You Really Sirius? (1953) |

| Yves Tanguy | French/American | Known for his distinctive landscapes populated by enigmatic, ambiguous forms resembling marine invertebrates or sculpted rock formations. His detailed, illusionistic spaces often evoke a sense of desolation, mystery, and infinite horizons, bathed in a strange, otherworldly light. | Indefinite Divisibility (1942), Mama, Papa is Wounded! (1927), Multiplication of the Arcs (1954) |

| André Breton | French | Though primarily a writer and poet, he was the chief theoretician and “pope” of Surrealism, publishing the Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, which defined the movement. He organized exhibitions and brought together many of the key artists, emphasizing “pure psychic automatism.” | (Primarily a writer/theoretician, not known for visual artworks, but his writings were foundational) |

| Meret Oppenheim | Swiss/German | Known for her provocative and witty object assemblages that subvert familiar items from their everyday context, challenging perceptions of femininity and desire. Her most famous work perfectly embodies the Surrealist spirit of unexpected juxtapositions. | Object (Déjeuner en fourrure) (1936) (Fur-covered teacup, saucer, and spoon) |

While Picasso was never a formal member, the story of his relationship with surrealism is a fascinating and complex one. Picasso’s work in the late 1920s and early 1930s showed a strong affinity with surrealist ideas. His dramatic shifts in style, particularly his distorted and fragmented figures, mirrored the surrealist interest in the unconscious and the irrational. He was a close friend to many surrealists, and his work from this period, such as Guernica, can be seen through a surrealist lens, using monstrous, disfigured forms to express the horror of war. While he never fully committed to the group’s agenda, his influence on surrealism and its influence on him are undeniable.

The contributions of women to the surrealist movement were foundational, though they were often overlooked by art history for many years. The movement’s focus on dreams and the subconscious was a powerful tool for female artists to explore their inner worlds and challenge societal norms. The relationship between surrealism and women is one of mutual liberation, both for the art and for the artists. Figures like Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Dorothea Tanning created intricate, magical worlds that were deeply personal and highly symbolic. Carrington’s paintings often featured strange, hybrid creatures, reflecting her interest in mythology and personal transformation, while Varo’s work was filled with meticulous details of mystical, alchemical processes. Frida Kahlo, while not a surrealist herself, was a close associate of the group and her powerful, dreamlike self-portraits are often categorized with surrealist works because of their emotional intensity and fantastical symbolism, serving as raw explorations of her physical and psychological pain.

Collecting Surrealist Art: Surrealism Art for Sale

For those interested in owning a piece of this dreamlike world, the market for surrealism art for sale is varied and accessible. While masterpieces by the movement’s founders command astronomical prices, you can find original paintings by lesser-known artists as well as more affordable options like prints and surrealism art posters. The prices for a piece of surrealism art buy can range from very high for a masterpiece by Dalí to quite reasonable for a contemporary artist. The internet has made it easier than ever to explore galleries and online marketplaces that specialize in surrealist art. When collecting, it’s wise to distinguish between limited edition prints—which are produced in a finite number and often signed and numbered by the artist, making them more valuable—and open-edition posters, which are mass-produced and primarily for decorative purposes.

When looking for pictures of surrealism art or surrealism art pictures, remember that the quality can vary. It’s always best to research the artist and the gallery before making a purchase. You might also consider exploring abstract surrealism for a different aesthetic that still captures the spirit of the movement. For a deeper dive, there are countless books on surrealism, from historical accounts to artist biographies and collections of works. These books can provide invaluable insight into the movement’s philosophy and the personal stories of the artists who shaped it.

The Enduring Legacy of Surrealism

The influence of surrealism extends far beyond the canvas, seeping into film, literature, fashion, and even psychology. Filmmakers like Luis Buñuel collaborated with Salvador Dalí on films like Un Chien Andalou, which used bizarre, dreamlike imagery to shock and provoke. In literature, writers embraced automatic writing and poetic juxtapositions. The surrealist sensibility continues to inform contemporary art, fashion design, and even advertising, where dreamlike visuals are often used to sell products. Its legacy is a testament to the power of the imagination and the enduring fascination with the world beneath the surface of our consciousness. The surrealists taught us to look at the familiar with fresh eyes, to question reality, and to find beauty in the bizarre. Whether you are a collector, an artist, or simply an admirer, the journey into the dreamscape of surrealism is an adventure worth taking.

Video: Understanding Surrealism

FAQs: Guide to Surrealism Art

Q: Why is surrealism still important today? A: Surrealism continues to be influential because its emphasis on the unconscious mind and imagination remains relevant. Its ideas have impacted many subsequent art forms and it provides a powerful framework for exploring the human psyche and challenging conventional reality.

Q: What is the main concept of surrealism? A: The main concept is “pure psychic automatism,” which is the belief that true creativity comes from the subconscious mind, free from the constraints of logic, reason, or moral preoccupation.

Q: How did surrealism differ from Dada? A: Surrealism grew out of Dada, sharing its anti-rational stance, but it moved beyond Dada’s nihilism and embraced a more constructive, philosophical goal: to find a “super-reality” by uniting the worlds of dreams and reality.

Q: What are the main themes of surrealist art? A: Common themes include dreams, fantasy, the subconscious, desire, eroticism, and the uncanny. Artists often explored these through symbolic imagery and unexpected juxtapositions.

Q: How can I recognize surrealist art? A: Look for dreamlike or illogical scenes, a mix of unrelated objects, distorted figures, and a feeling of the uncanny. The art often aims to challenge your perception of reality and provoke thought.

List of Citations

- Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Seaver and Helen Lane, University of Michigan Press, 1969.

- Dalí, Salvador. The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. Dial Press, 1942.

- Chadwick, Whitney. Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. Thames & Hudson, 1985.

- Gopnik, Adam. “The Great Surrealist Joke.” The New Yorker, 19 February 2007.

- Nadeau, Maurice. The History of Surrealism. Translated by Richard Howard, Macmillan, 1965.