Remember those goofy cartoon images you used to insert into school presentations? The smiling computers, generic handshakes, and oversized light bulbs that made every PowerPoint look like it came from 1997? Well, those clip art graphics are now hanging in art galleries, selling for thousands of dollars as legitimate paintings. This isn’t a joke—it’s one of the most fascinating transformations in contemporary art history.

Key Points:

- Clip art evolved from physical printer’s cuts to digital files that became worthless through infinite reproduction

- Contemporary painters are transforming these disposable digital images into expensive, one-of-a-kind artworks

- This artistic movement challenges our ideas about what makes art valuable and questions the boundaries between high and low culture

- The flat, simple aesthetic of 90s clip art has become a powerful symbol of early digital culture and technological nostalgia

Listen to our Podcast

The Surprising History of Those Cheesy Graphics

When Clip Art Actually Meant Clipping Things

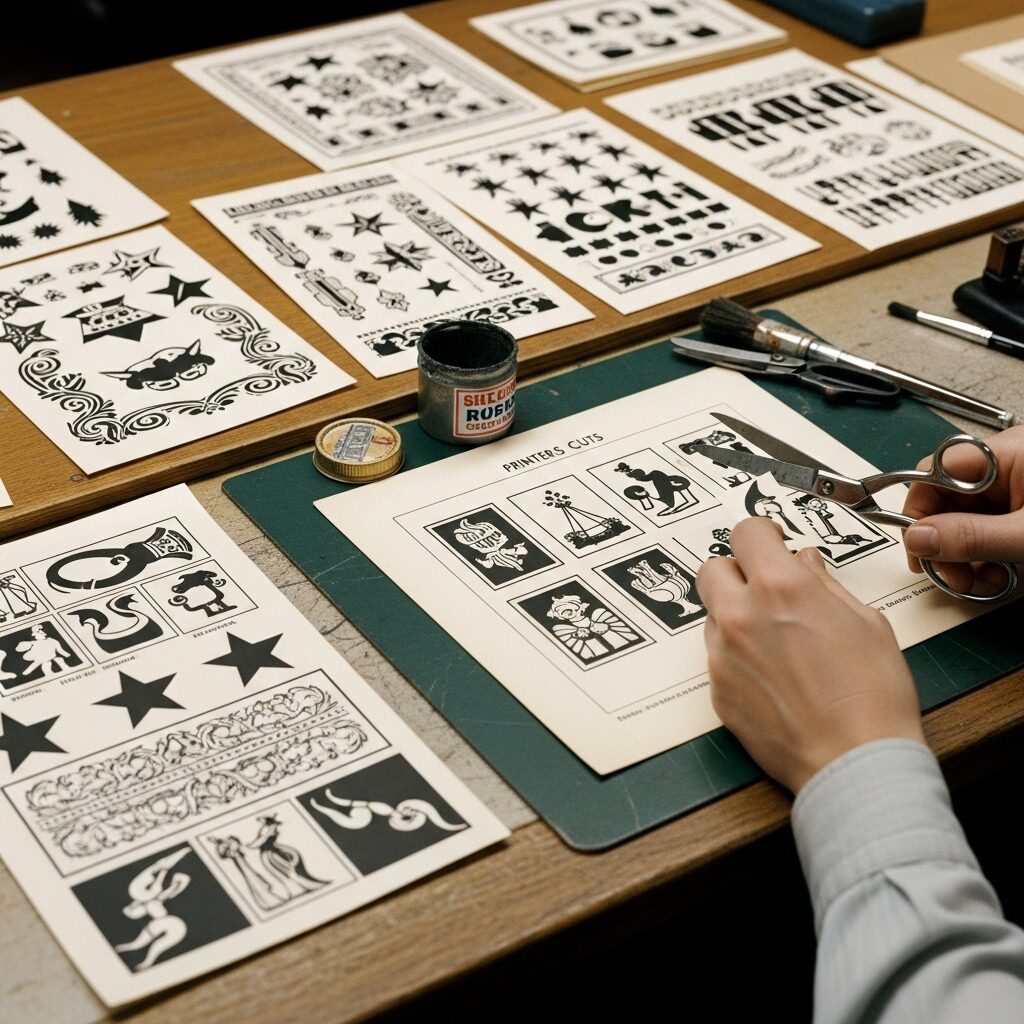

Before computers took over the world, “clip art” wasn’t just a clever name—it literally described what people did. In the printing industry, artists would create reusable images called “printer’s cuts” or “stock cuts.” These were distributed in actual printed booklets, and when someone needed a graphic for their newspaper or flyer, they would physically clip it out with scissors and glue it onto their page layout using rubber cement.This manual paste-up process was the standard workflow until the early 1990s.

Think about that for a second. Every time someone wanted to use the same image, they needed a physical copy of it. That made these graphics valuable—they were scarce, and someone had to do real work to reproduce and place them. It was the complete opposite of today’s world where you can copy an image a million times with a single click.

The Desktop Revolution: From Scarcity to Abundance

Everything changed in 1983 when VCN ExecuVision launched for the IBM PC with the first library of professionally drawn digital clip art. Then in 1984, Apple’s MacPaint made it possible for anyone to create simple graphics without professional training. Suddenly, you didn’t need to be a skilled illustrator to add pictures to your documents.

But the real explosion happened with CD-ROMs in the early 1990s. Traditional print companies like Dover Publications and new software companies like T/Maker started offering massive collections of electronic clip art. We’re talking thousands of images on a single disc. This shift toward quantity over quality changed everything—digital images went from valuable commodities to basically worthless files that came free with your software.

Microsoft Word 6.0 in 1996 represented the institutional peak of clip art, with its famous gallery of cartoonish images. But by 2014, Microsoft quietly closed its Office.com Clip Art Library, admitting that people could just search Google for images instead. The age of centralized clip art collections was officially over.

Key Milestones in Clip Art Evolution:

| Era | What Happened | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1980s | Physical printer’s cuts that were manually clipped and pasted | Images had real value because they were scarce and required labor |

| 1983 | First digital clip art library launched | Graphics became digital files for the first time |

| Early 1990s | CD-ROMs enabled mass distribution | Images lost value through infinite reproduction |

| 1996 | Microsoft Word 6.0 peaks the clip art era | Clip art becomes universally accessible and familiar |

| 2014 | Microsoft closes Office clip art library | End of the institutional clip art era; web search takes over |

Why Clip Art Looks the Way It Does

The Technical Secret Behind Those Flat Graphics

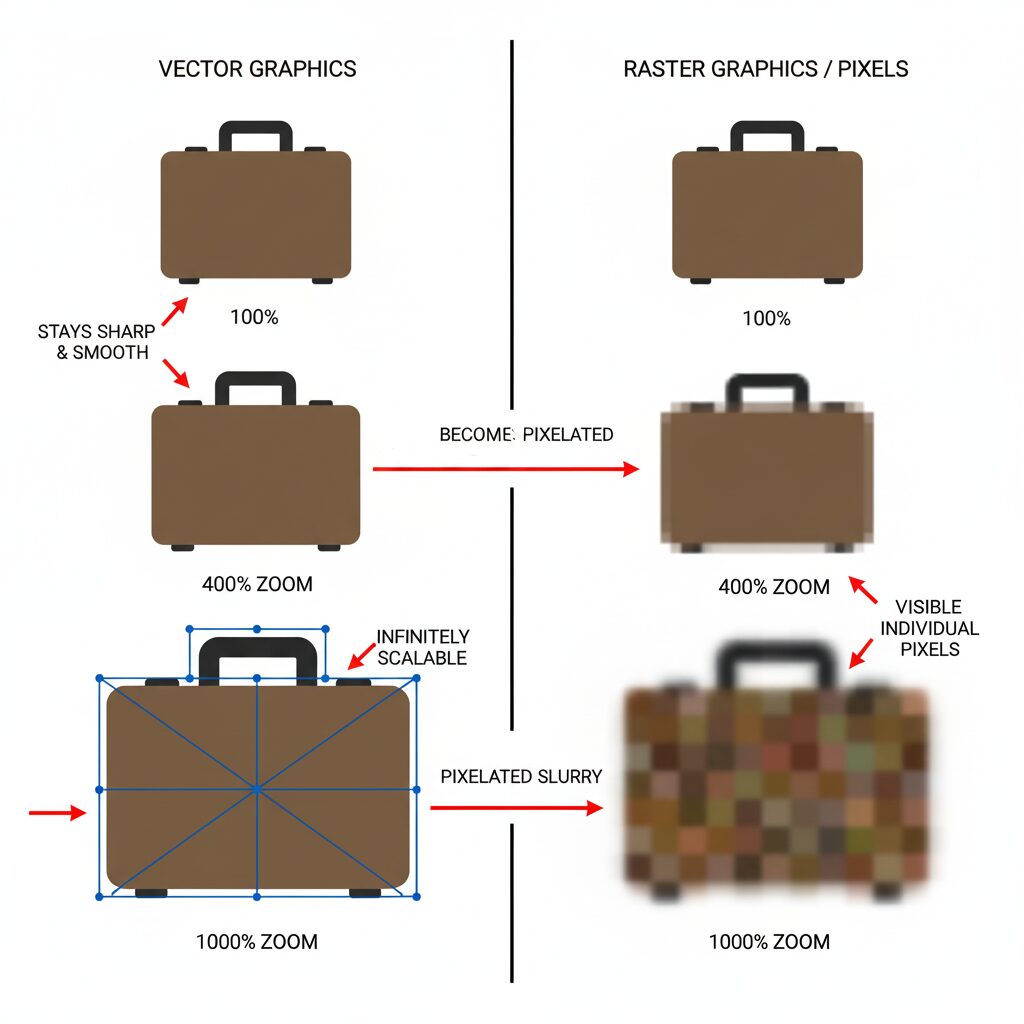

Have you ever zoomed way in on a photo and seen it turn into fuzzy squares? That’s because photos are made of pixels—tiny dots arranged in a grid. This is called raster graphics. But clip art uses something called vector graphics, which are mathematically defined lines and curves rather than pixels.

This technical difference is huge. Vector images can be scaled to any size without losing quality—they maintain perfectly sharp lines and flat colors no matter how big you make them. That’s why clip art has that distinctive look: clean edges, flat colors, and simplified shapes. It wasn’t just an aesthetic choice—it was necessary for the technology.

Those limitations actually created a unique visual language. Early computers didn’t have much memory, so graphics had to be simple and efficient. The result? An aesthetic reduction that favored flatness and iconic simplicity—the most basic way to represent a concept. A suitcase became a simple rectangle with a handle. A person became a circle head with a stick body.

Vector vs. Raster Graphics Comparison:

| Feature | Vector Clip Art | Raster Photos |

|---|---|---|

| Made From | Mathematical equations and curves | Grid of colored pixels |

| When You Zoom In | Stays perfectly sharp forever | Gets fuzzy and pixelated |

| Visual Style | Flat colors, clean lines, simplified shapes | Gradients, photographic detail, realistic textures |

| File Types | .AI, .EPS, .SVG | .JPG, .PNG, .GIF |

| Perfect For | Logos, icons, simple illustrations | Photographs, complex images |

The Birth of “Ugly” Digital Aesthetics

Here’s something wild: what we now consider the “ugly” look of 90s clip art was actually cutting-edge technology at the time. Desktop publishing in the 1980s and 1990s forced designers to evolve, creating new visual languages that established professionals often perceived as ugly or flawed.

This happened because regular people—not trained designers—suddenly had access to design software. The result was a lot of Comic Sans, rainbow gradients, and yes, excessive clip art. Professional designers were horrified. But decades later, contemporary movements like “anti-design” now embrace these visually chaotic or imperfect qualities, with the Y2K aesthetic championing maximalism and glitchy visuals.

How Clip Art Became “Art” Art

Following Andy Warhol’s Recipe for Success

To understand why painters are now creating works based on clip art, you need to know about Pop Art. In the 1960s, artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein challenged the distinction between fine art and everyday visual culture by elevating commercial, mass-produced artifacts. Warhol painted Campbell’s soup cans. Lichtenstein painted comic book panels.

Clip art is the perfect 21st-century version of this strategy. Like Warhol’s soup cans, clip art graphics are:

- Mass-produced for commercial purposes

- Completely generic and recognizable to everyone

- Created without a single identifiable artist

- Originally considered “low culture” or disposable

When a contemporary painter takes a cheesy Microsoft Word clip art image and paints it by hand on a large canvas, they’re doing exactly what Warhol did: forcing us to question what makes something “art” versus just a commercial product.

The Post-Internet Art Movement

Today’s clip art painters are part of what critics call “Post-Internet art.” This doesn’t mean art made after the internet—it means art that addresses how the internet has fundamentally changed how we see and understand images.

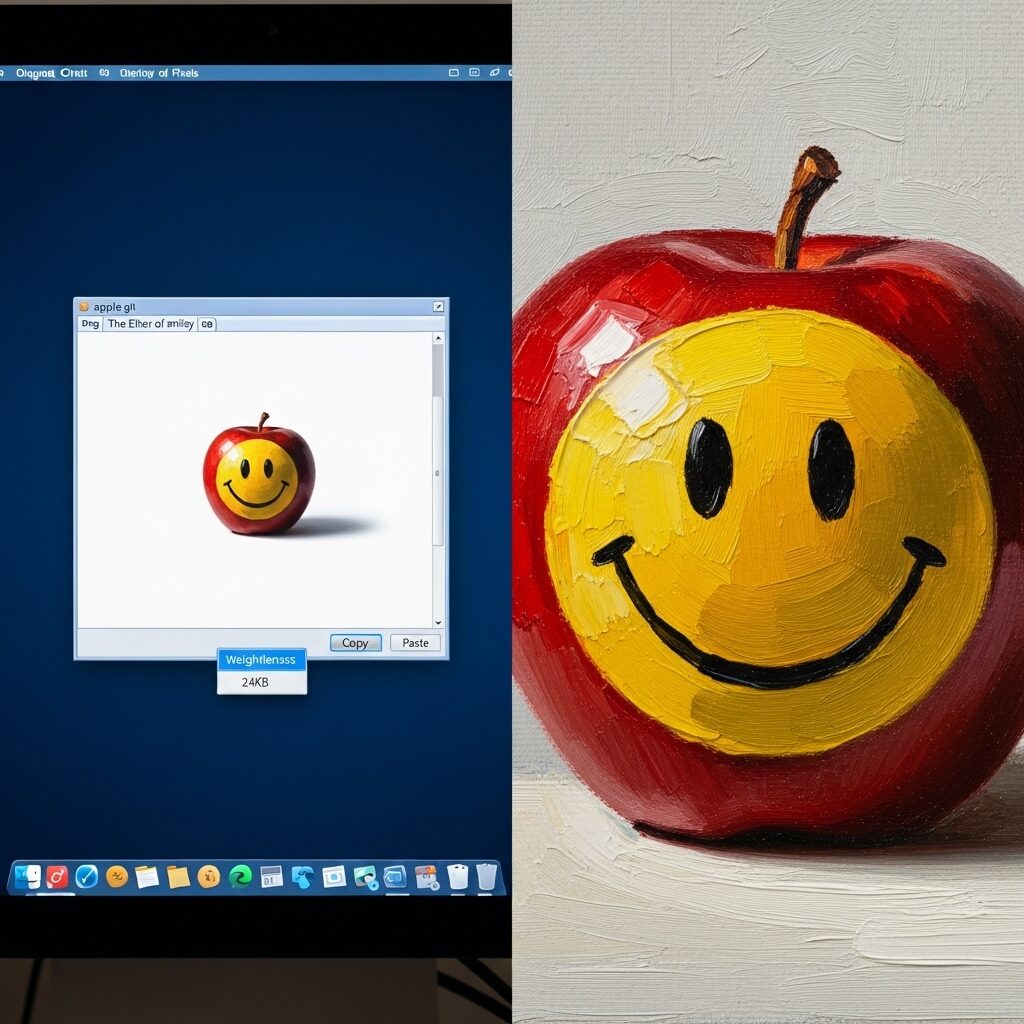

These artists often reference the low-fidelity digital aesthetic of early software like Microsoft Paint, characterized by flat, simple, and visually jarring imagery. By physically painting these crude digital images, they’re performing what critics call “the materialization of the ephemeral”—turning something that exists only as weightless data into a physical, unique object.

Think about it: a digital clip art file costs nothing and can be copied infinitely. But a painting based on that same image might sell for $10,000 or more. This transformation converts the non-scarce, intangible digital file into a unique, high-value, market-scarce object. It’s a total reversal of the image’s original purpose.

“By elevating the most standardized, functional image to the status of fine art, contemporary painters challenge the mechanisms of taste and critique the speed at which digital culture discards its visual heritage.”

The Generic Iconography: Clip Art’s Evolution

The Legal Puzzle: Can You Actually Paint Someone Else’s Clip Art?

Understanding Royalty-Free Doesn’t Mean Free-Free

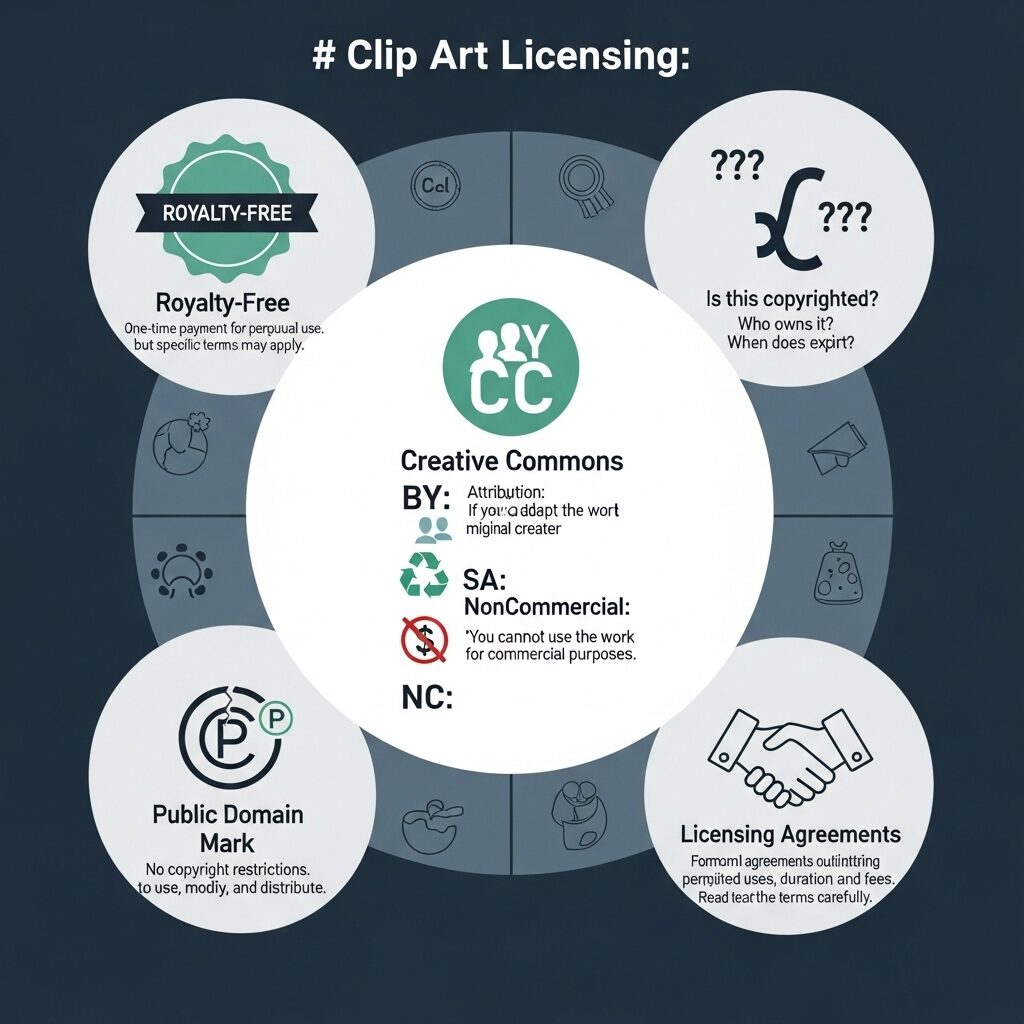

Here’s where things get complicated. Most commercial clip art from the CD-ROM era came with something called a “royalty-free” license. But royalty-free doesn’t mean you can do whatever you want—it means you pay once and get broad usage rights, though restrictions often apply to resale.

For painters, this creates a legal gray area. If you download clip art and paint it exactly as is, then sell that painting, are you violating the license? It depends on:

- The specific license terms of that clip art collection

- How much you’ve transformed the original image

- Whether your use qualifies as “transformative” under copyright law

The famous appropriation artists of the 1980s—like Richard Prince and Jeff Koons—fought major legal battles over using commercial images in their art. Copying a copyrighted image for personal use or study is generally protected as free speech, but selling that work without significant transformation violates intellectual property rights.

Clip Art Licensing for Artists:

| License Type | Can You Use It Commercially? | The Catch | Safe for Painting? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Royalty-Free | Sometimes (varies by vendor) | Usually restricts resale as a primary product | Gray area—read the fine print carefully |

| Creative Commons BY | Yes | Must credit the creator | Yes, if you provide attribution |

| Creative Commons BY-SA | Yes | Your work must use the same license | Problematic—conflicts with selling unique art |

| Public Domain | Yes | None—completely free | Safest choice |

The Transformative Use Defense

Smart artists don’t just copy clip art exactly—they transform it. This might mean:

- Changing the colors, composition, or scale dramatically

- Combining multiple images in new ways

- Adding significant original elements

- Creating commentary on the original image

The more you change the original image, the stronger your legal position. The practice of appropriation serves to comment on contemporary society and the nature of art itself, which courts have sometimes protected as transformative use.

For contemporary painters working with clip art, the safest approach is to use images that are clearly in the public domain, have Creative Commons licenses, or to transform the images significantly enough that they become new artistic statements rather than mere reproductions.

Why Nostalgia Makes This Art Movement Powerful

Digital Archaeology and Collective Memory

When contemporary artists choose 90s clip art specifically, they’re not just picking random graphics—they’re performing cultural archaeology, referencing a shared digital history and generational memory. For people who grew up making school reports in the 1990s and early 2000s, these images trigger instant recognition and nostalgia.

These graphics function as time capsules. That pixelated computer with the smiley face? It represents an era when computers were exciting and new, not the anxiety-inducing devices we carry in our pockets. That generic clip art handshake? It evokes a time when business culture was somehow even more corporate and formal than today.

By painting these obsolete graphics at large scale, artists are essentially building monuments to a discarded digital past. These images serve as vernacular icons that signify early computing experiences and the rapid obsolescence of digital styles.

The Deeper Message About Technology and Value

There’s something profound happening when an artist spends weeks carefully painting an image that was designed to be created in seconds and used once. The labor involved in oil painting—mixing colors, building up layers, achieving the perfect flat appearance—contrasts dramatically with the effortless reproduction of digital files.

This contrast asks important questions:

- What makes something valuable—scarcity or quality?

- Who decides what counts as “good” art versus “bad” design?

- How quickly do we throw away visual culture that was once everywhere?

- What does it mean that we can now generate unlimited images with AI?

As AI-generated images become more common, classic clip art becomes definitively historicized, securing the generic, unauthored icon a place within fine art discourse. Today’s clip art paintings may be tomorrow’s historical artifacts documenting a specific technological moment.

The Bigger Picture: Low Culture Becomes High Art

Lowbrow Art and Pop Surrealism

Clip art fits perfectly into the lowbrow art movement (also called Pop Surrealism), which originated in countercultural movements and intentionally fuses high and low culture by incorporating symbols from cartoons, comics, and mass media.

Academic art critics have historically ignored clip art because it lacks a singular, recognizable author and doesn’t fit into codified aesthetic systems. But that’s exactly why contemporary artists love it. By bringing clip art into galleries and museums, they’re challenging the gatekeepers who decide what deserves to be called art.

Celebrating Camp and Kitsch

There’s something delightfully rebellious about taking the tackiest, most dated digital graphics and declaring them worthy of serious artistic attention. This embrace of “bad taste” or kitsch has a long history in art, but clip art takes it to a new level because these images were never even intended to be noticed—they were meant to be functional background elements.

The anti-design movement embraces visually chaotic or imperfect qualities, specifically rejecting the rational clarity of minimalism. When a painter lovingly recreates a clip art graphic that professional designers would consider embarrassingly dated, they’re making a statement about who gets to define good taste.

Where to Find and Use Clip Art Legally

If you’re inspired to try creating your own clip art-based artwork, here are reliable sources:

Free Public Domain and Creative Commons Sources:

- Wikimedia Commons – Massive collection of freely usable images

- Pixabay – Free vectors and illustrations with no attribution required

- FreeImages – Royalty-free stock images and illustrations

- OpenClipart – Public domain clip art library

Commercial Stock Sources (read licenses carefully):

- Shutterstock – Extensive 90s clip art collections

- Getty Images – High-quality vintage illustrations

- Adobe Stock – Professional vector graphics with clear licensing

Remember: always read the license terms before using any image in artwork you plan to sell. When in doubt, transform the image significantly or stick to public domain sources.

The Future of Generic Images

From Clip Art to AI Generation

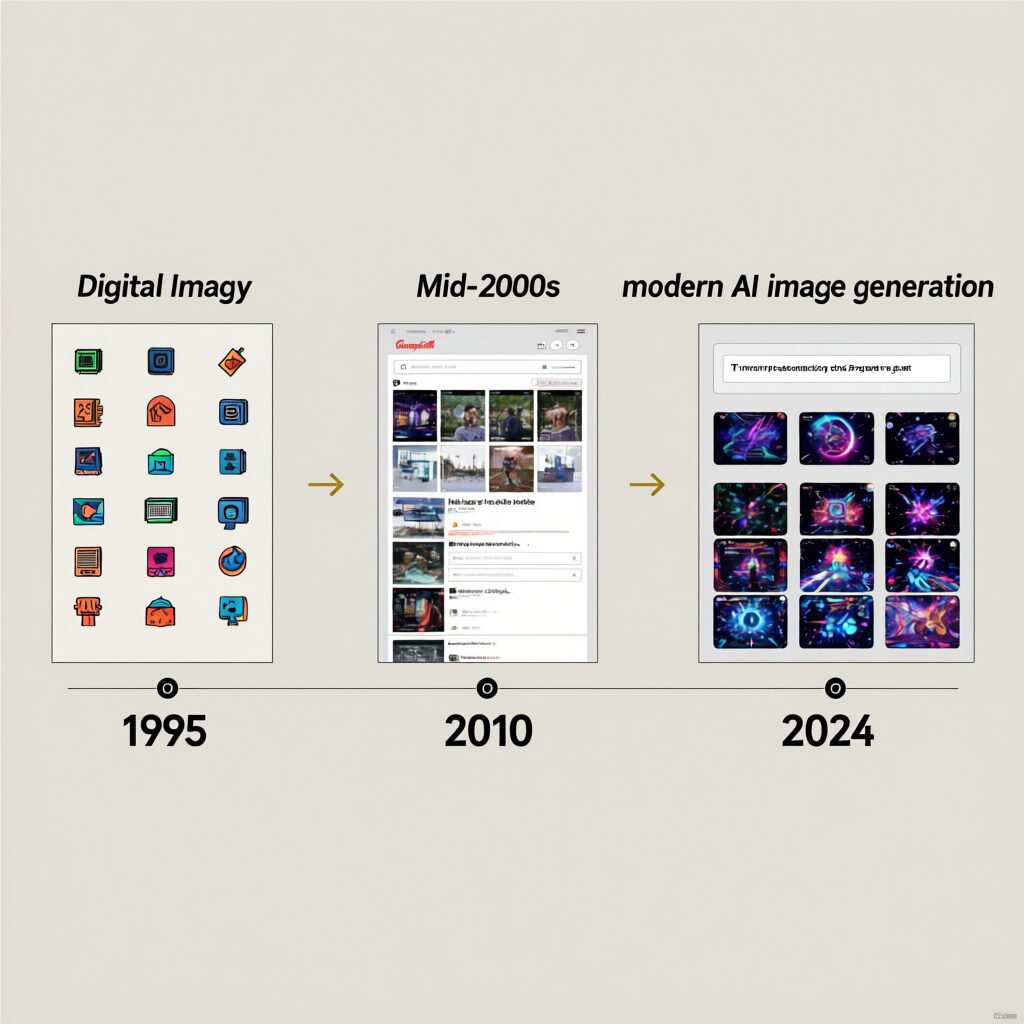

The conversation around clip art and painting has become even more interesting with the rise of AI image generation. AI photography and illustration tools allow users to create highly customized visuals in minutes, offering flexibility that standard stock photos cannot match.

This means traditional clip art is now doubly nostalgic—it represents both the obsolete aesthetic of early digital design AND an obsolete method of image production. You can now type “cartoon handshake” into an AI generator and get thousands of unique variations instantly, making the fixed, generic clip art image even more historically specific.

Some artists are already beginning to paint AI-generated images, raising new questions about authorship and originality. If clip art paintings challenged ideas about value and authenticity, AI paintings push those questions even further.

Why This Movement Matters

The transformation of clip art from disposable utility to fine art painting represents more than just a quirky trend. It demonstrates how:

- Technology shapes aesthetics – The limitations of early digital tools created a distinctive visual language we now recognize and value

- Value is constructed, not inherent – The same image can be worthless data or a $50,000 painting depending on context

- Digital culture deserves preservation – Seemingly trivial artifacts like clip art are actually important historical documents

- High and low culture boundaries are artificial – There’s no real reason Campbell’s soup cans or clip art shouldn’t be art subjects

Frequently Asked Questions About Clip Art in Fine Art

Is clip art considered real art? Clip art itself is commercial illustration, but when contemporary painters use clip art imagery in their work, they’re creating fine art that comments on digital culture, authorship, and value. The art isn’t the clip art file—it’s the painted interpretation and the conceptual statement being made.

Can I legally sell paintings of clip art? It depends on the license of the specific clip art you’re using. Public domain and Creative Commons images are generally safe, while commercial clip art may have restrictions. Significantly transforming the image strengthens your legal position. Always check the license terms before selling derivative work.

Why would anyone pay thousands for a painting of free clip art? Buyers aren’t just purchasing the image—they’re buying a unique, handmade object that makes a conceptual statement about digital culture, nostalgia, and the art market itself. The painting’s value comes from its materiality, the artist’s labor, and its place within contemporary art discourse.

What’s the difference between appropriation art and copyright infringement? Appropriation art uses existing images to comment on culture and society, which can qualify as transformative use. Copyright infringement is simply copying someone else’s work. The key difference is whether your use adds new meaning, message, or context that transforms the original.

How do you paint something to look exactly like digital clip art? Artists typically use techniques that emphasize flatness and eliminate visible brushstrokes—similar to hard-edge painting. This might involve precise masking, multiple thin layers, or even airbrush techniques to achieve that characteristic digital flatness.

Why is 90s clip art specifically popular with artists now? The 1990s represents a specific moment when digital tools became democratized but were still primitive by today’s standards. People who grew up during this era experience strong nostalgia for these graphics, making them powerful cultural symbols of early digital life.

Is this related to vaporwave or Y2K aesthetics? Yes! The clip art painting movement shares DNA with these internet-born aesthetics that celebrate and critique early digital and pre-millennium visual culture. All three movements use nostalgic, dated digital imagery to comment on technology, capitalism, and collective memory.

Where can I see examples of clip art paintings in galleries? Post-Internet art galleries and contemporary art museums increasingly feature this work. Search for “Post-Internet painting” or “digital vernacular art” to find current exhibitions. Many artists also showcase this work on platforms like Instagram and Artsy.

Clip art has completed a remarkable journey—from physical printer’s cuts to disposable digital files, and now to serious subjects of contemporary painting. What began as a purely functional tool for illustrating documents has become a powerful lens for examining how we create, value, and discard visual culture in the digital age. Whether you see these paintings as brilliant conceptual art or just expensive jokes, they’ve succeeded in making us reconsider those silly graphics we took for granted. And really, that’s what good art should do—make us look at familiar things in completely new ways.

Additional Resources

Art History and Criticism:

- MoMA’s Guide to Appropriation in Art – Museum of Modern Art’s explanation of appropriation art movements

- Art Post-Internet PDF – Comprehensive guide to Post-Internet art movement

- Why Are Painters Remaking Famous Images? – Aperture – Contemporary photography magazine’s analysis

Legal Resources:

- Creative Commons License Guide – Official guide to understanding Creative Commons

- Copyright Law for Visual Artists – Creative Pinellas – Practical copyright guidance

- Transformative Use in Appropriation Art – Academic analysis of legal issues

Technical Background:

- A Brief History of Clip Art – Detailed timeline of clip art development

- Understanding Vector Graphics – Adobe’s explanation of vector vs. raster

- Microsoft Kills Office Clip Art – TIME – The end of the institutional clip art era

Contemporary Design Movements:

- Ugly Design Revolution – Artsy – How “ugly” aesthetics became influential

- Lowbrow and Pop Surrealism – Understanding the lowbrow art movement

- Painting Pixels – Maddox Gallery – Gallery overview of digital-inspired painting

Image Sources:

- Shutterstock 90s Clipart Collections – Commercial source for nostalgic graphics

- Getty Images 1990s Illustrations – High-quality vintage digital imagery

- FreeImages Vector Collections – Free simplicity-themed vectors