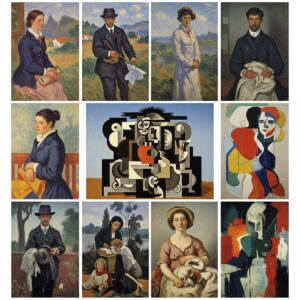

Painting styles and movements have been pivotal in shaping the course of art history. From the intricate brushwork of Renaissance paintings to the bold strokes of Abstract Expressionism, each movement reflects the thoughts, emotions, and philosophies of its era.

Artists throughout time didn’t just create for the sake of beauty. Many painted to respond to the cultural, political, or social conditions they were living in. This makes the study of art movements not just an exploration of creative expression but also a lens to view history.

Let’s break down the most important painting movements in history, look at the techniques behind them, and explore how these styles influenced one another over time.

Key Point Summary: Painting Styles and Movements

- Historical Evolution: Art movements developed as responses to cultural, political, and social conditions, with each movement building upon or reacting against its predecessors

- Renaissance (14th-17th century): Established realism foundations with linear perspective, chiaroscuro lighting, and humanistic themes that influenced all future art education

- Baroque (17th century): Introduced dramatic emotional expression through dynamic compositions and theatrical lighting, influencing later Romanticism and visual storytelling

- Impressionism (Late 19th century): Revolutionized painting by prioritizing light, color, and spontaneous brushwork, marking the beginning of modern art’s break from academic traditions

- Abstract Expressionism (Post-WWII): Shifted focus from depicting objects to expressing pure emotion through abstract forms, establishing America as a major art center

- Pop Art (1950s-1960s): Bridged high and low culture by incorporating mass media imagery, challenging traditional art hierarchies and making art more accessible

- Technical Innovations: Each movement contributed specific advances – Renaissance perspective, Baroque drama, Impressionist color theory, Fauve bold expression, and Abstract gestural methods

- Cultural Mirror: Art movements reflect their era’s values, technologies, and social concerns, from Renaissance humanism to Pop Art’s consumer culture commentary

Glossary of Art Styles

Listen to our Podcast on Art Movements

Chronological Timeline of Major Art Movements

Early & High Renaissance

c. 1400–1520

A “rebirth” of classical ideals, celebrating humanism, realism, and scientific accuracy.

Mannerism

c. 1520–1600

A reaction against Renaissance harmony, using artificiality and elongated figures.

Baroque

c. 1600–1750

An art of drama, emotional intensity, and grandeur, often with high-contrast lighting.

Neoclassicism

c. 1750–1850

A return to the order and rationality of classical art, emphasizing civic virtue.

Romanticism

c. 1780–1850

Prioritizing emotion, individualism, and the sublime power of nature over reason.

Ukiyo-e (Japan)

c. 1603-1868

Woodblock prints celebrating the “floating world” of urban Japanese life and leisure.

Realism

c. 1848–1870

Depicting the unvarnished truth of everyday life, with a focus on the working class.

Impressionism

c. 1865–1885

Capturing the fleeting “impression” of a moment, focusing on the effects of light and color.

Post-Impressionism

c. 1885–1910

Moving beyond visual reality to explore structure, symbolism, and personal emotion.

Symbolism

c. 1880–1910

Suggesting the invisible world of dreams, ideas, and emotions through symbolic imagery.

Fauvism

c. 1905–1908

Using intense, non-naturalistic color and “wild beast” brushwork for emotional expression.

Expressionism

c. 1905–1920

Distorting form and color to express the artist’s inner feelings or psychological state.

Cubism

c. 1907–1914

Breaking down objects into geometric forms to show multiple viewpoints at once.

Futurism

c. 1909–1914

A celebration of dynamism, speed, technology, and the energy of modern machines.

Harlem Renaissance

c. 1918–1937

A cultural revival celebrating modern, sophisticated, and self-determined Black identity.

Surrealism

c. 1924–1950

Unlocking the unconscious mind through bizarre, dreamlike, and illogical imagery.

Abstract Expressionism

c. 1943–1965

Large-scale abstract art emphasizing the physical act of painting and emotional intensity.

Pop Art

c. 1950s–1970s

Using imagery from consumer culture and mass media to challenge fine art traditions.

Minimalism

c. 1960s–1970s

Stripping art down to its essential components of form, color, and industrial material.

Conceptual Art

c. 1960s–Present

Prioritizing the idea behind the artwork over the physical object itself.

Street Art

c. 1980s–Present

Using public space as a canvas for social commentary and direct communication.

From Renaissance to Street Art: A Comprehensive Guide to Art Styles and Movements

Art is more than just a pretty picture. It’s a language, a historical record, and a window into the human soul. Each brushstroke and every creative choice is part of a conversation that has spanned centuries. To understand art, we need to understand its vocabulary: the styles and movements that have shaped the way we see the world.

An art movement is a period of time when artists work with a shared philosophy, style, and set of goals. These movements don’t happen in a vacuum; they are born from revolution, scientific discovery, and profound cultural shifts. This guide will take you on a chronological journey through the most influential art movements, exploring their core ideas, key artists, and the masterpieces that defined them.

The Renaissance and The Age of Grandeur

1. The Renaissance (c. 1400–1520)

- Core Idea: A “rebirth” of the classical ideals of ancient Greece and Rome, celebrating humanism, realism, and individual potential.

- Key Characteristics:

- Emphasis on proportion, anatomy, and perspective.

- Integration of religious themes with humanist philosophy.

- Use of techniques like sfumato (smoky blending) and chiaroscuro (strong light/dark contrast).

- Key Artists: Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian.

- Iconic Artwork: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503-1506) This painting is the quintessence of Renaissance humanism. The subject is not a saint but a secular individual. Leonardo uses sfumato to create a subtle, lifelike softness, particularly around the corners of the mouth and eyes, giving her an enigmatic quality. The portrait’s realism and psychological depth were revolutionary.

2. Baroque (c. 1600–1750)

- Core Idea: Art that evokes intense emotion, drama, and grandeur, often in service of the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation.

- Key Characteristics:

- High-contrast lighting and deep shadows (tenebrism).

- Dynamic compositions, often with diagonal lines to suggest movement.

- Dramatic, emotional, and theatrical subject matter.

- Key Artists: Caravaggio, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Rembrandt van Rijn, Peter Paul Rubens.

- Iconic Artwork: Caravaggio’s The Calling of Saint Matthew (c. 1599-1600) Caravaggio masterfully uses tenebrism to create a scene of intense, divine drama. A stark beam of light cuts across a dark tavern, illuminating Christ who points towards Matthew, the tax collector. The light acts as a symbol of God’s call, freezing a moment of profound spiritual transformation with theatrical and gritty realism.

The Age of Revolution and Emotion

3. Neoclassicism (c. 1750–1850)

- Core Idea: A reaction against the extravagance of the Baroque, returning to the perceived purity and order of classical art in the age of the Enlightenment.

- Key Characteristics:

- Clean lines, sharp detail, and structured compositions.

- Subject matter focused on classical history and mythology.

- Emphasis on logic, order, and civic virtue.

- Key Artists: Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Antonio Canova.

- Iconic Artwork: Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784) This painting is a manifesto of Neoclassical values. It depicts three Roman brothers swearing an oath to their father to fight for their city. The composition is rigid and stage-like, with strong, clear lines and a focus on masculine self-sacrifice and duty to the state. It became an emblem of the French Revolution.

4. Romanticism (c. 1780–1850)

- Core Idea: A movement that prioritized emotion, individualism, and the sublime power of nature over the logic and reason of Neoclassicism.

- Key Characteristics:

- Intense, often turbulent, emotional scenes.

- Emphasis on nature as a wild, untamable force.

- Loose, expressive brushwork and rich color.

- Key Artists: Eugène Delacroix, Caspar David Friedrich, J.M.W. Turner, Francisco Goya.

- Iconic Artwork: Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (c. 1818) This painting captures the essence of the Romantic sublime. A lone figure stands on a rocky precipice, his back to the viewer, contemplating a vast, fog-shrouded landscape. It’s a scene not just about a view, but about the human experience of awe, introspection, and being overwhelmed by the power of nature.

The Modern Gaze

5. Realism (c. 1848–1870)

- Core Idea: To depict contemporary life and society as it truly was, without idealization or artificiality.

- Key Characteristics:

- Focus on everyday subjects, including the working class and rural life.

- A truthful, objective, and often gritty approach.

- Muted, earthy color palettes.

- Key Artists: Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, Édouard Manet.

- Iconic Artwork: Gustave Courbet’s The Stone Breakers (1849) Courbet’s masterpiece is a political and artistic statement. It depicts two anonymous laborers, one young and one old, engaged in back-breaking work. By painting them on a large canvas typically reserved for historical or mythological subjects, Courbet elevated the common man and presented an unvarnished look at the harsh realities of poverty.

6. Impressionism (c. 1865–1885)

- Core Idea: To capture the fleeting “impression” of a moment, focusing on the shifting effects of light and color.

- Key Characteristics:

- Short, thick brushstrokes and visible texture (impasto).

- Painting outdoors (en plein air) to observe light directly.

- Focus on modern urban life and landscapes.

- Key Artists: Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro.

- Iconic Artwork: Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (1872) The painting that gave the movement its name, Impression, Sunrise is the definitive example of Impressionist goals. Monet uses rapid, broken brushstrokes to capture the fleeting moment the sun burns through the morning mist in the port of Le Havre. The focus is not on the details of the boats, but on the sensation of light and atmosphere.

7. Post-Impressionism (c. 1885–1910)

- Core Idea: Not a single style, but a reaction to Impressionism. Artists pushed beyond capturing visual reality to explore emotion, structure, and symbolism.

- Key Characteristics:

- Varied styles: from the scientific pointillism of Seurat to the emotional expression of Van Gogh.

- Symbolic and personal use of color and form.

- A move towards abstraction.

- Key Artists: Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin.

- Iconic Artwork: Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889) While the Impressionists painted what they saw, Van Gogh painted what he felt. The Starry Night is a turbulent, emotional landscape painted from his asylum window. The swirling, energetic brushstrokes and intense, non-naturalistic colors convey his inner turmoil and spiritual awe, making the sky a direct reflection of his psyche.

The Dawn of Abstraction

8. Fauvism (c. 1905–1908)

- Core Idea: A radical use of intense, non-naturalistic color to express emotion, liberating color from its descriptive duty.

- Key Characteristics:

- Vivid, often clashing colors applied directly from the tube.

- Bold brushwork and simplified forms.

- Key Artists: Henri Matisse, André Derain.

- Iconic Artwork: Henri Matisse’s Woman with a Hat (1905) When this painting was exhibited, a critic derisively called Matisse and his peers “Les Fauves” (The Wild Beasts), naming the movement. The portrait of Matisse’s wife uses aggressive slashes of green, blue, orange, and purple across her face and background. The colors do not describe her appearance but are used to build a vibrant, emotional, and decorative composition.

9. Cubism (c. 1907–1914)

- Core Idea: To represent a subject from multiple viewpoints simultaneously, breaking it down into geometric forms.

- Key Characteristics:

- Fragmented objects and flattened perspectives.

- A muted, monochromatic color palette in its early phase (Analytical Cubism).

- The later introduction of collage elements (Synthetic Cubism).

- Key Artists: Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque.

- Iconic Artwork: Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) This groundbreaking, controversial painting shattered traditional notions of perspective and beauty. Picasso depicts five nude figures with sharp, geometric bodies and faces inspired by Iberian sculpture and African masks. The space is compressed and ambiguous, presenting the figures from multiple angles at once, effectively launching a new visual language.

10. Futurism (c. 1909–1914)

- Core Idea: An Italian movement that celebrated dynamism, speed, technology, and the machine, aiming to capture the energy of modern life.

- Key Characteristics:

- “Lines of force” and rhythmic patterns to depict movement.

- Fragmented forms inspired by Cubism.

- Subjects like cars, trains, and urban chaos.

- Key Artists: Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla.

- Iconic Artwork: Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) This sculpture embodies the Futurist obsession with motion. It’s not a figure frozen in a pose, but a figure blurred by its own powerful stride through space. The bronze form appears to be shaped by the wind and its own velocity, creating a dynamic synthesis of the object and its environment.

Art Beyond the Visual

11. Surrealism (c. 1924–1950)

- Core Idea: To unlock the power of the unconscious mind, influenced heavily by Sigmund Freud’s theories on dreams and the subconscious.

- Key Characteristics:

- Bizarre, dreamlike scenes and illogical juxtapositions.

- Automatism (drawing or painting without conscious thought).

- Hyper-realistic rendering of fantastical subjects.

- Key Artists: Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Max Ernst, Joan Miró.

- Iconic Artwork: Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931) Perhaps the most famous Surrealist painting, it depicts melting clocks draped over a desolate landscape. Dalí described these as a representation of the “softness” and “relativity” of time, a concept he discovered while observing melting Camembert cheese. The precise, realistic technique applied to an impossible scene creates a jarring and unforgettable dreamscape.

12. Abstract Expressionism (c. 1943–1965)

- Core Idea: A New York-based movement that emphasized spontaneous, subconscious creation. The act of painting itself became the subject.

- Key Characteristics:

- Large-scale canvases.

- Non-representational imagery.

- Two main branches: action painting (energetic gestures) and color field painting (large flat areas of solid color).

- Key Artists: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko.

- Iconic Artwork: Jackson Pollock’s Number 1, 1950 (Lavender Mist) (1950) A prime example of “action painting,” Pollock did not use an easel. He laid his canvas on the floor and dripped, poured, and flung paint from all sides. The result is not a picture of something, but a record of the artist’s physical actions. The intricate web of lines and colors creates a pulsating, immersive visual field.

Art of the People and the Idea

13. Pop Art (c. 1950s–1970s)

- Core Idea: To challenge the traditions of fine art by incorporating imagery from consumerism and popular culture.

- Key Characteristics:

- Use of imagery from advertising, comic books, and mass-produced objects.

- Bold, flat colors and techniques borrowed from commercial printing (e.g., silk-screening).

- A sense of irony and detachment.

- Key Artists: Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns.

- Iconic Artwork: Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962) This work consists of 32 canvases, each depicting a different flavor of Campbell’s soup. By presenting this mundane, mass-produced object in a gallery setting, Warhol erased the boundary between fine art and commercial design. He questioned the nature of originality and celebrated (or satirized) the uniformity of American consumer culture.

14. Minimalism & Conceptual Art (c. 1960s–1970s)

- Core Idea: Minimalism sought to strip art down to its essential components of form and material. Conceptual art went further, arguing that the idea behind the artwork is more important than the finished object.

- Key Characteristics:

- Minimalism: Industrial materials, geometric forms, lack of emotional expression.

- Conceptual Art: The artwork can be a set of instructions, a photograph, a text, or even just a thought.

- Key Artists: (Minimalism) Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt. (Conceptual) Joseph Kosuth, Marcel Duchamp (as a predecessor).

- Iconic Artwork: Joseph Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs (1965) This work perfectly illustrates conceptual art. It presents a manufactured chair, a photograph of that chair, and a dictionary definition of the word “chair.” The piece forces the viewer to ask: Which is the real chair? Kosuth’s work is not about the object itself, but about the idea and language used to represent it.

Expanding the Canon

15. Ukiyo-e (Japan, c. 1603-1868)

- Core Idea: “Pictures of the Floating World,” this genre of woodblock prints and paintings depicted the pleasures of urban life in Edo-period Japan.

- Key Characteristics:

- Strong outlines, flat areas of color, and bold compositions.

- Subjects included beautiful courtesans, kabuki actors, and famous landscapes.

- Crucial Influence: When these prints arrived in Europe in the 19th century, their asymmetrical compositions and flattened perspective profoundly influenced the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, including Monet, Degas, and Van Gogh.

16. The Harlem Renaissance (USA, c. 1918–1937)

- Core Idea: An intellectual and cultural revival of African American art, music, literature, and politics centered in Harlem, New York. Visual artists sought to create a modern, distinctly Black aesthetic.

- Key Characteristics:

- Celebration of Black life, history, and identity.

- Stylistic influences from African art, Cubism, and Art Deco.

- Strong narrative and symbolic content.

- Key Artists: Aaron Douglas, Jacob Lawrence, Augusta Savage.

- Iconic Artwork: Aaron Douglas’s Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery Through Reconstruction (1934) This mural panel is a powerful example of the movement’s aesthetic. Douglas uses geometric silhouettes and radiating bands of color to create a dynamic, symbolic history of the African American experience. A central figure holds a ballot, representing empowerment and hope, while pointing toward the US Capitol, symbolizing the continuing struggle for civil rights.

17. Street Art (c. 1980s–Present)

- Core Idea: Art created in public spaces, often unsanctioned. It is a direct communication with the public, bypassing the traditional gallery system.

- Key Characteristics:

- Use of stencils, spray paint, wheatpaste posters, and murals.

- Often carries a political or satirical message.

- Site-specific and ephemeral by nature.

- Key Artists: Banksy, Shepard Fairey, Jean-Michel Basquiat.

- Iconic Artwork: Banksy’s Girl with Balloon (c. 2002) Initially appearing as a stencil on a London wall, this simple yet poignant image of a young girl reaching for a heart-shaped balloon has become a global symbol of hope, loss, and innocence. Its fame skyrocketed in 2018 when a version of it famously self-destructed after being sold at auction, a quintessential act of anti-consumerist street art philosophy.

From the divine perfection of the Renaissance to the rebellious ideas of Conceptual Art, the story of art is the story of humanity. Each movement is a reaction to what came before and an inspiration for what comes next. By understanding these styles, we can better appreciate the rich, complex, and ever-evolving world of art.

Final Thoughts

From the Renaissance to Pop Art, each movement reshaped the artistic landscape, reflecting the changing values, cultures, and technologies of its time. Pop Art, in particular, showcased how the boundary between fine art and commercial culture could be blurred, making art more accessible and reflective of the everyday world.

By studying these movements, we gain insight into the creative evolution of human thought and expression. Whether through the grandeur of Baroque or the cheeky commentary of Pop Art, every movement has left a mark on history, and understanding them enriches our view of the world.

Study Guide

FAQ: Painting Styles and Movements

What is the difference between an art style and an art movement?

An art style refers to the visual characteristics and techniques used in creating artwork – such as brushwork, color choices, and composition methods. An art movement, however, is a group of artists who share common philosophies, goals, or responses to their cultural moment. While Renaissance is a movement, the specific techniques of linear perspective or chiaroscuro are styles within that movement.

Which painting movement came first: Impressionism or Realism?

Realism came first, emerging in the mid-19th century, followed by Impressionism in the late 19th century. Realism focused on depicting everyday life with detailed accuracy, while Impressionism later shifted toward capturing fleeting light effects and spontaneous moments with looser brushwork.

What makes Renaissance art different from Baroque art?

Renaissance art emphasized harmony, proportion, and classical ideals with balanced compositions. Baroque art, while building on Renaissance techniques, added dramatic emotion, dynamic movement, and theatrical lighting effects. Renaissance sought perfection and order, while Baroque aimed to engage viewers emotionally through grandeur and drama.

Why is Abstract Expressionism considered so important in art history?

Abstract Expressionism marked America’s first major contribution to international art movements and shifted the art world’s center from Paris to New York. It represented a complete break from representational art, focusing instead on pure emotional expression through abstract forms, color, and gesture. This movement influenced virtually all subsequent contemporary art forms.

How did Pop Art change the art world?

Pop Art democratized art by incorporating everyday objects and mass media imagery, challenging the idea that art must be serious or highbrow. Artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein used commercial techniques and popular culture references, making art more accessible and relevant to contemporary life. This movement blurred the boundaries between fine art and commercial culture.

What is the connection between Romanticism and Expressionism?

Both movements prioritized emotion over rational representation, though they emerged in different centuries. Romanticism (late 18th-mid 19th century) celebrated individual feeling and the sublime in nature, while Expressionism (early 20th century) used distorted forms and bold colors to convey psychological states. Romanticism’s emphasis on emotional authenticity laid the groundwork for Expressionism’s psychological exploration.

Which art movement is considered the beginning of modern art?

Most art historians consider Impressionism the beginning of modern art because it broke away from academic traditions of detailed realism and studio-based painting. Impressionists’ focus on light, color, and outdoor painting (plein air) marked the first major departure from Renaissance-established conventions, paving the way for all subsequent modern movements.

How did social and political events influence painting movements?

Many movements emerged as direct responses to historical events. The Protestant Reformation influenced Baroque’s dramatic religious imagery, the Industrial Revolution sparked Romanticism’s return to nature, and both World Wars impacted Abstract Expressionism’s emotional intensity. Pop Art reflected post-war consumer culture, while Realism responded to social inequality during industrialization.

What techniques did Impressionist painters use that were different from earlier movements?

Impressionists used broken brushstrokes, pure color application, and painted outdoors to capture natural light. Unlike earlier movements that used smooth blending and studio lighting, Impressionists applied paint in visible dabs and strokes, often leaving areas of canvas visible. They also abandoned traditional composition rules, sometimes cropping figures at canvas edges like photographs.

Why did Fauvism get its name “wild beasts”?

The term “Fauvism” comes from “les fauves,” meaning “wild beasts” in French. Art critic Louis Vauxcelles coined this term in 1905 when he saw Henri Matisse’s and André Derain’s paintings with their bold, non-naturalistic colors. The vivid, seemingly uncontrolled use of pure color straight from paint tubes appeared “wild” compared to traditional color harmony principles.