Right. Listen. I know what you’re thinking. “Me writing about art? The man who once compared a Kandinsky to something his dog did on the carpet?” Yes, well. Here we are. And I’m going to tell you something that’ll make all those turtleneck-wearing, latte-sipping gallery types splutter into their overpriced oat milk: art cannot be neutral. Never has been. Never will be. End of.

You see, the very act of creating something – anything – is a statement. It’s like trying to be “neutral” about which side of the road to drive on. You can’t just hover in the middle and hope for the best. That’s not neutrality. That’s a crash waiting to happen.

The Myth of the Blank Canvas

Now, they’ll tell you that a blank canvas is neutral. Pure potential. An empty vessel waiting to be filled. Bollocks. Complete and utter bollocks. The moment you choose that canvas over, say, the side of a building or a piece of driftwood or the bonnet of a perfectly good Aston Martin, you’ve made a choice. You’ve taken a position. You’ve planted your flag.

And here’s the thing: even if you leave the canvas blank – which some absolute muppet probably has done and sold for millions – that’s still not neutral. That’s a statement about minimalism, or conceptual art, or perhaps a statement about having the nerve to charge people money for literally nothing. Which, fair play, takes some doing.

The Artist’s Impossible Position

Every single decision an artist makes is loaded with meaning. The color? That’s saying something. The size? That’s saying something. The fact they bothered to get out of bed and make anything at all? That’s definitely saying something, particularly if they live in Britain where it’s raining sideways and the heating costs more than a small yacht.

You can’t paint a mountain without deciding whether it’s majestic or menacing. You can’t paint a person without revealing what you think about humanity. Even painting a bloody apple is a minefield. Is it fresh and vibrant? Is it rotting? Is it a symbol of temptation, knowledge, health, or the fact that you couldn’t afford a better subject?

Context Is King (And He’s Quite Pushy)

And then—oh, this is where it gets properly interesting – there’s context. Even if, somehow, you managed to create something genuinely neutral (you didn’t, but let’s pretend), the world around it won’t be. Your art exists in a time, a place, a culture. It’s viewed by people with opinions, experiences, and an alarming tendency to see what they want to see.

A painting of a flag is just a painting until it’s hanging in a war museum. Then it’s not neutral anymore. It’s loaded with grief, pride, nationalism, or protest, depending on who’s looking at it and what they had for breakfast.

The Viewer Ruins Everything

This brings us to the most annoying part of the whole business: the audience. You know what viewers do? They bring their own baggage. Their politics, their memories, their inexplicable fondness for interpretive dance. They look at your work and decide what it means, often in complete defiance of what you actually intended.

You could paint a picture of a sunset – just a lovely, straightforward sunset, the sort you’d see from a beach in the Maldives while drinking something with an umbrella in it – and someone will decide it’s about climate change, or mortality, or the decline of Western civilization. And you can stamp your feet and insist it’s just a bloody sunset, but it’s too late. They’ve decided.

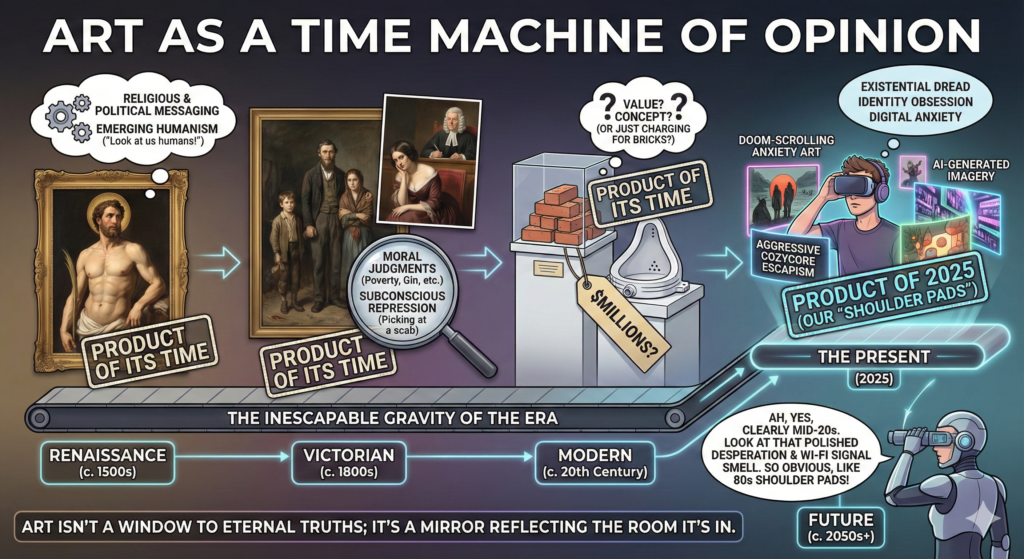

Art as a Time Machine of Opinion

Every piece of art is also, whether it likes it or not, a product of its era. Renaissance art? Absolutely stuffed with religious and political messaging. Victorian paintings? Full of moral judgments about everything from poverty to the perils of gin. Modern art? Well, that’s mostly about seeing how much you can charge people for a pile of bricks or a urinal.

You can’t escape it. Even if you try to make something “timeless,” you’re making it in this time, with these materials, based on these ideas. Future generations will look at it and say, “Ah, yes, this is clearly from 2025,” in the same way we look at shoulder pads from the 1980s and wonder what on earth everyone was thinking.

The Politics of Everything

And don’t even get me started on politics. Everything is political if you squint hard enough. A painting of flowers? Could be about femininity, fertility, environmentalism, or the Dutch tulip bubble of 1637. A portrait? Class, power, gender, race – it’s all in there whether you meant it or not.

Even choosing not to paint certain things is a choice. Not painting war while war is happening? That’s a statement. Not painting poverty while surrounded by it? Also a statement. Sometimes quite a loud one.

The Beautiful Impossibility

So here’s what I’ve come to understand, much to my surprise and slight irritation: the impossibility of neutral art is actually what makes art interesting. If art could be neutral, it would be wallpaper. Pleasant enough, sure, but ultimately just there to cover the cracks.

Art matters because it takes a position, even when it’s trying desperately not to. It matters because it reflects the chaos and conviction of whoever made it. It matters because it makes people feel something – anger, joy, confusion, or the overwhelming urge to leave the gallery and find a proper pub.

Do Can Art Be Neutral? The Glorious Mess

The truth is, art is messy. It’s complicated. It’s full of contradictions and arguments and people who can’t agree on anything except that everyone else is wrong. And that’s rather brilliant, actually.

Because in a world where everyone’s trying to be neutral, to not offend, to please everyone all the time, art stands there like a defiant teenager and says, “No. I’m going to mean something, even if it makes you uncomfortable.”

And honestly? We need more of that. Not less.

The Bottom Line

So can art be neutral? No. Not even slightly. Not even if you tried with every fiber of your being. Not even if you painted a perfectly average beige square on a perfectly average beige wall in a perfectly average room in Milton Keynes.

And you know what? That’s exactly how it should be. Because art without opinion, without position, without some bloody conviction behind it, isn’t art at all. It’s just… stuff. And we’ve got quite enough stuff already, thank you very much.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to look at pictures of the new Bugatti. That’s art you can actually drive. Much better.