Welcome to a powerhouse of creativity! Tate Modern, housed in a former power station on the banks of the River Thames, is London’s incredible home for modern and contemporary art. It’s not just a museum; it’s a journey through the wild, wonderful, and sometimes weird ideas of the last 120 years. This guide will be your treasure map to the top 10 Tate Modern paintings and artworks. Get ready to explore explosive comic book art, mind-bending dreams, and canvases that capture pure emotion. Let’s dive into a world where artists broke all the rules and created masterpieces that still get us talking today.

Whaam! (1963) by Roy Lichtenstein

Description: BOOM! This giant, two-part painting feels like it was ripped straight from a comic book. On one side, a fighter jet fires a rocket; on the other, an enemy plane explodes in a blaze of red and yellow. Lichtenstein took a small comic panel and blew it up to an epic scale, making us see this ‘low’ art form as something monumental and powerful. It’s a loud, exciting, and unforgettable piece of Pop Art that challenges the idea of what belongs in a fancy art gallery. The artwork was inspired by a panel from the 1962 DC comic book ‘All-American Men of War’.

What to Look For: Notice the Ben-Day dots, the tiny dots used in old-school comic printing, which Lichtenstein painstakingly painted by hand using a stencil. Also, look at the bold, black outlines and the primary colors (red, yellow, blue), which mimic the simple printing style of comics. The onomatopoeic ‘WHAAM!’ in the right panel is the star of the show, making you almost hear the explosion.

Techniques: Lichtenstein used Magna acrylic and oil paint on two large canvases. He projected the original comic book image onto the canvas, traced it, and then filled in the colors and his signature Ben-Day dots using a metal screen as a stencil to create a mechanical, mass-produced look, even though it was all done by hand.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

Marilyn Diptych (1962) by Andy Warhol

Image for Marilyn Diptych could not be loaded.

Description: This is one of the most famous images of Hollywood star Marilyn Monroe, but it’s not just a portrait. Andy Warhol, the king of Pop Art, created this piece shortly after her death. It features fifty images of her face, half in dazzling color and the other half in fading black and white. The artwork explores ideas of celebrity, death, and how someone’s image can be endlessly repeated until it almost loses its meaning, like a product on a supermarket shelf. The term ‘diptych’ is usually used for religious altarpieces, suggesting Warhol saw Marilyn as a modern-day goddess or saint.

What to Look For: Compare the two sides. The left side is vibrant and full of life, representing Marilyn’s public persona as a glamorous star. The right side is ghostly and faded, with smudges and imperfections. This side suggests the tragedy of her private life and the fading of her memory after death. The repetition makes her face feel less like a person and more like a brand.

Techniques: Warhol used a silkscreen printing process. He took a single publicity photo of Monroe from the film ‘Niagara’ and printed it over and over. The imperfections in the printing process, like smudges and uneven ink, were deliberately kept to show the contrast between the flawless celebrity image and the messy reality of life and death.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

The Snail (1953) by Henri Matisse

Description: Doesn’t look much like a snail, does it? This giant, colorful artwork was made by Henri Matisse when he was in his 80s and too frail to paint. Instead, he started ‘drawing with scissors’, cutting shapes from paper painted by his assistants and arranging them into vibrant collages. ‘The Snail’ shows his incredible genius for color and form, creating a sense of movement and energy from simple shapes that spiral outwards like a snail’s shell. Matisse considered this work the culmination of his entire career.

What to Look For: Try to trace the spiral shape with your eyes, starting from the green square in the middle and moving outwards. Notice how the complementary colors (like orange next to blue, and red next to green) are placed to make each other pop. The arrangement seems simple, but it’s a masterful balance of color, shape, and rhythm.

Techniques: This is a ‘gouache découpée’, or painted paper cut-out. Matisse’s assistants painted large sheets of paper with gouache paint. Matisse then cut directly into the color, a process he felt was more direct than painting. The shapes were then arranged and pasted onto a large paper background.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

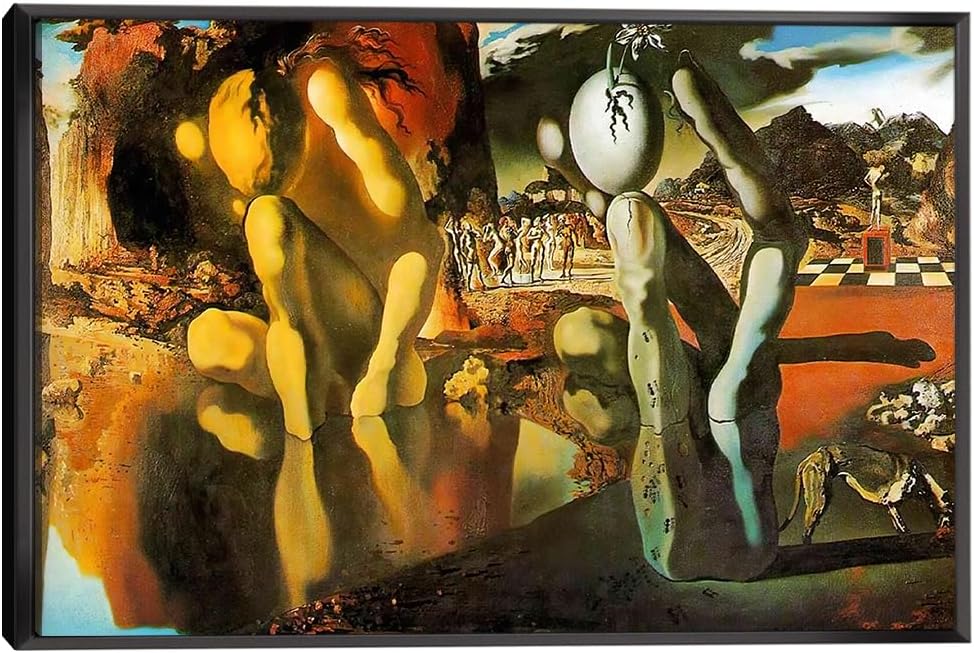

Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) by Salvador Dalí

Description: Get ready to enter a dream world! Salvador Dalí was a master of Surrealism, an art movement that explored the subconscious mind. This painting tells the ancient Greek myth of Narcissus, a beautiful youth who fell in love with his own reflection. Dalí paints the moment of transformation: on the left, Narcissus stares into the water; on the right, a fossilized stone hand appears in the same pose, holding an egg from which a narcissus flower sprouts. It’s a classic Dalí mind-bender. Dalí took this painting to meet his hero, the famous psychologist Sigmund Freud, who was impressed by the artist’s psychological insight.

What to Look For: Squint your eyes and look at the two main figures – the kneeling Narcissus and the stone hand. They have the exact same outline! This is Dalí’s ‘paranoiac-critical method’, where he would create mind-boggling double images. In the background, you can spot all sorts of strange details, like a chessboard and a group of figures on the horizon.

Techniques: Dalí used a highly detailed, realistic oil painting style that he called ‘hand-painted color photographs’. This precise technique makes the bizarre, dreamlike subject matter feel even more unsettling and real. He painted on a small canvas to draw the viewer in closer to inspect the strange details.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

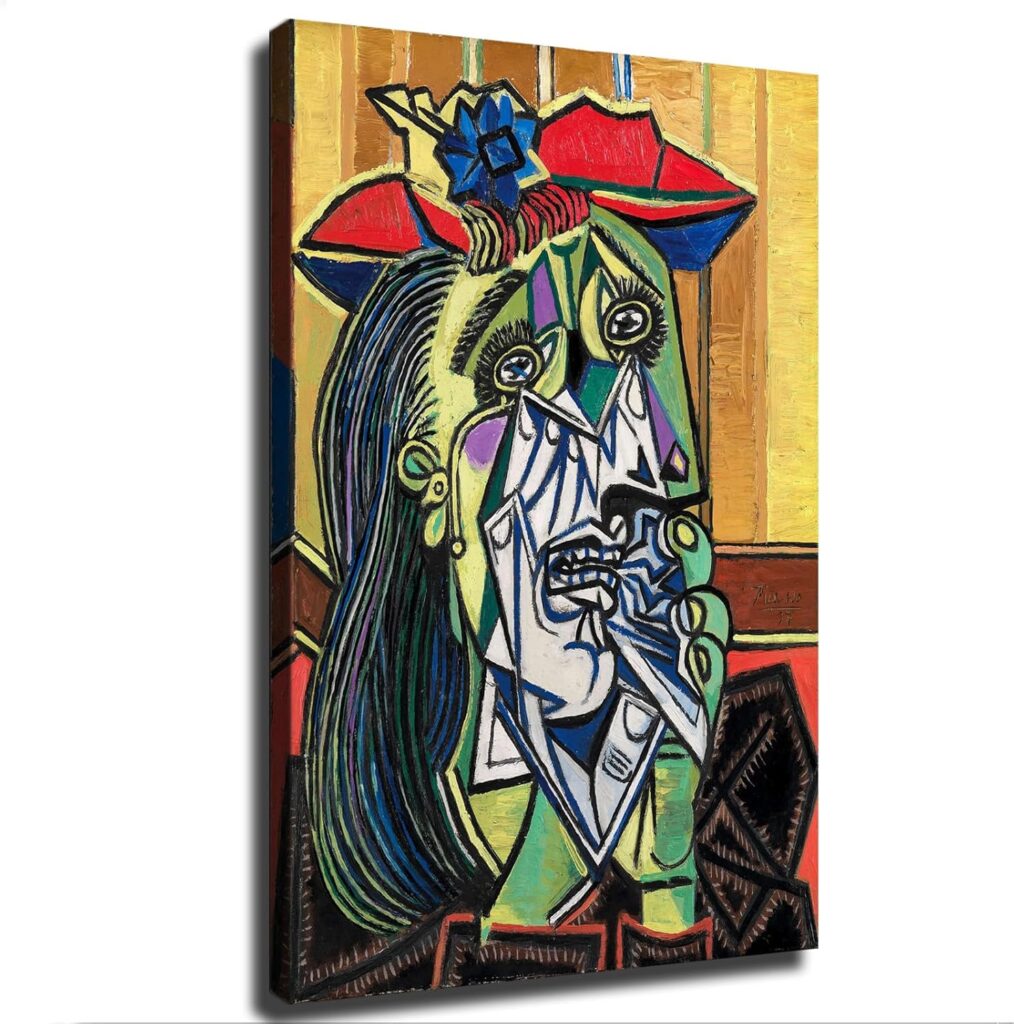

Weeping Woman (1937) by Pablo Picasso

Description: This painting is pure emotion. It’s not a calm, realistic portrait; it’s a raw, jagged picture of grief. Picasso painted this as a follow-up to his huge anti-war mural, ‘Guernica’. The woman, with her shattered-glass features and acidic colors, represents the universal suffering of war, especially its impact on innocent women and children. Her handkerchief looks like a shard of glass, and her eyes are like broken faucets of tears. The model for the painting was the photographer and artist Dora Maar, who was Picasso’s lover and muse at the time.

What to Look For: Focus on the woman’s face. Picasso breaks it apart and puts it back together in a style called Cubism. You can see her face from different angles at once. The harsh, angular lines and the sickly green and purple colors are used to express her intense pain and anguish, not to create a likeness.

Techniques: Picasso used oil on canvas, applying the paint with energetic, almost violent brushstrokes. He employed the principles of Cubism to fracture the woman’s form, showing multiple viewpoints simultaneously to convey her fragmented psychological state. The bold outlines and clashing colors heighten the emotional intensity.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

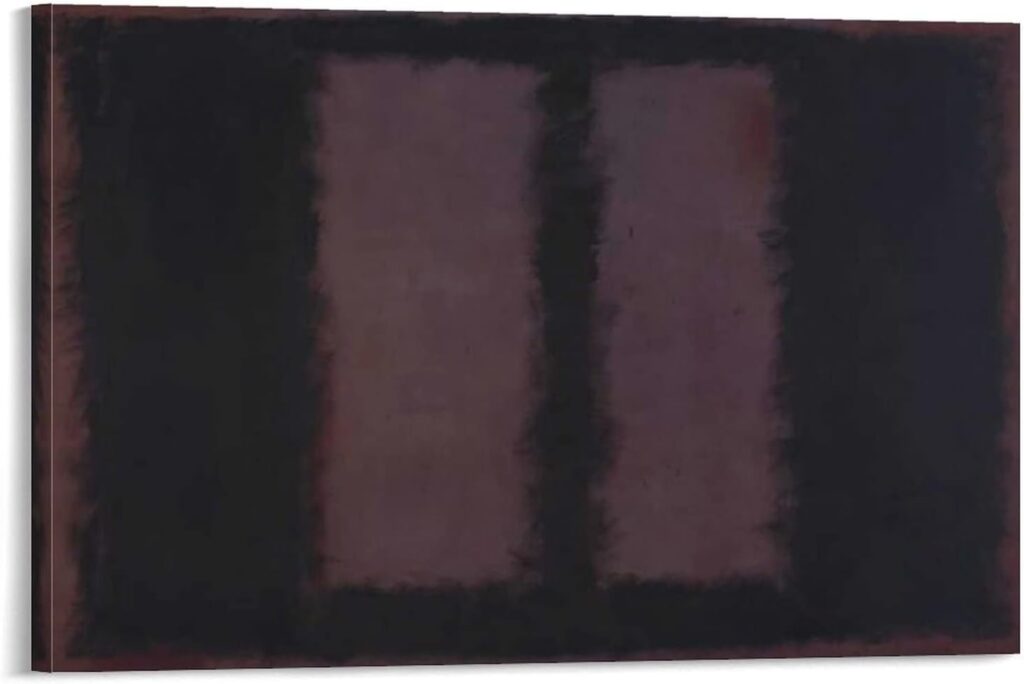

Black on Maroon (1958) by Mark Rothko

Description: Step into a quiet, meditative space. This is one of Mark Rothko’s famous Seagram Murals. He wanted to create paintings that would surround the viewer and create a deep emotional experience, almost like being in a chapel. The large, dark, rectangular shapes seem to hover and pulse with a soft, inner light. It’s not a picture of something; it’s a painting about feeling something – sadness, awe, or peace. These paintings were originally commissioned for the fancy Four Seasons restaurant in New York, but Rothko withdrew from the project because he felt the wealthy diners wouldn’t appreciate them properly.

What to Look For: Don’t just glance at it; stand in front of it for a few minutes. Let your eyes adjust to the subtle shifts in color. The soft, blurry edges of the shapes make them feel like they are floating. Rothko wanted you to have a personal, one-on-one experience with the artwork, so try to block everything else out and just feel.

Techniques: Rothko applied thin layers, or glazes, of oil paint on canvas. This layering of different colors creates a sense of depth and luminosity. He used a variety of tools, including brushes and rags, to create the soft, feathery edges that are a hallmark of his style.

Location in Museum: The Rothko Room

Estimated Value: Priceless

Number 14, 1951 (1951) by Jackson Pollock

Description: Imagine an artist laying a huge canvas on the floor and dancing around it, dripping, pouring, and flinging paint from cans and sticks. That’s how Jackson Pollock created this masterpiece. It’s not a picture of anything in particular; instead, it’s a record of an action. The tangled web of black, white, and brown lines creates a thrilling sense of energy, rhythm, and depth. It’s pure, expressive freedom on a canvas. Pollock’s unique style of action painting earned him the nickname ‘Jack the Dripper’.

What to Look For: Follow the lines with your eyes. Can you see how some drips are thick and others are thin? This shows how Pollock moved—sometimes fast, sometimes slow. The painting has no center; every part of the canvas is equally important. It’s like looking at a galaxy of stars or a complex city map.

Techniques: This is a prime example of Pollock’s ‘drip’ technique. He used liquid household enamel paint, which was easier to pour and drip than traditional oil paint. By moving his whole body as he worked, he was able to create complex, layered networks of lines without ever letting his brush touch the canvas.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

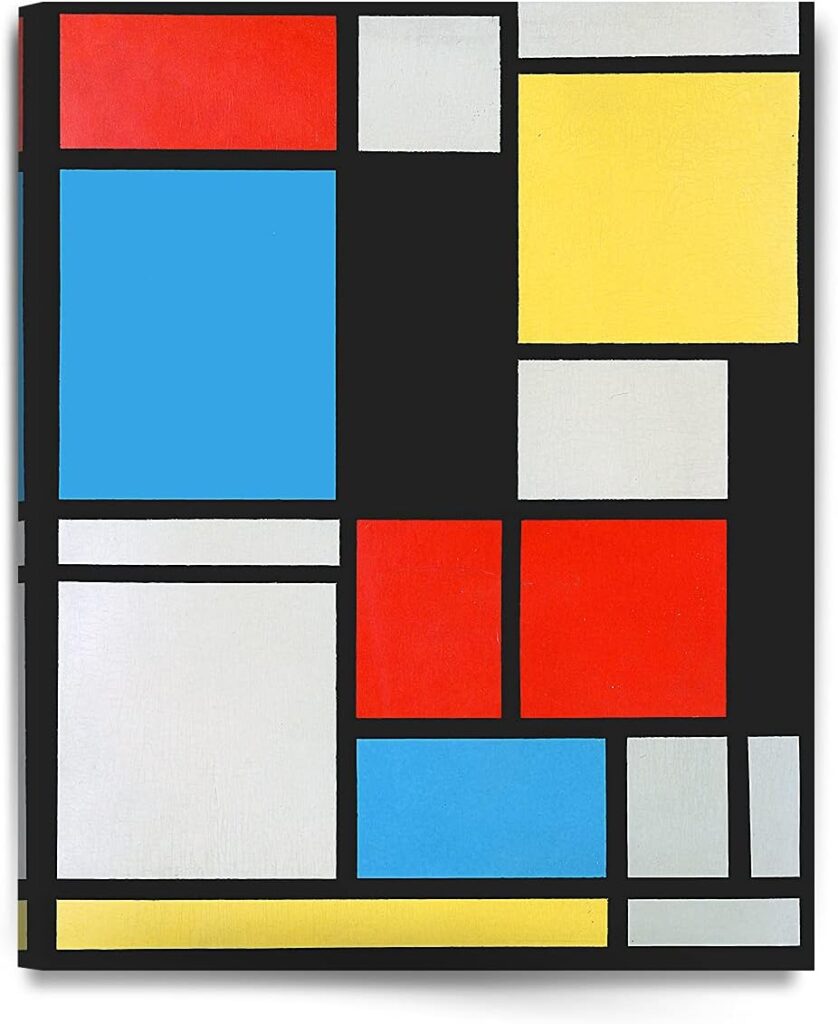

Composition C (No.III) with Red, Yellow and Blue (1935) by Piet Mondrian

Description: This painting is all about balance and harmony. Piet Mondrian believed that he could represent the underlying order of the universe using the simplest possible elements: straight black lines and blocks of primary colors (red, yellow, blue) on a white background. It might look like a simple design, but every line and block has been placed with incredible care to create a perfect sense of visual equilibrium. It’s a kind of visual music. Mondrian created this work after fleeing Nazi Germany for Paris, and it reflects his search for stability and order in a chaotic world.

What to Look For: Notice how the largest color block, the red square, is balanced by the smaller yellow and blue rectangles. The thick black lines create a grid that holds everything together, but they also vary in thickness. The composition feels both stable and dynamic at the same time, a perfect harmony of opposites.

Techniques: Mondrian used oil paint on canvas to create his ‘Neoplastic’ or ‘De Stijl’ compositions. He would meticulously plan his grids, using tape to create razor-sharp edges for his black lines and color blocks. His goal was to remove any trace of the artist’s hand and create a universal, purely abstract art.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

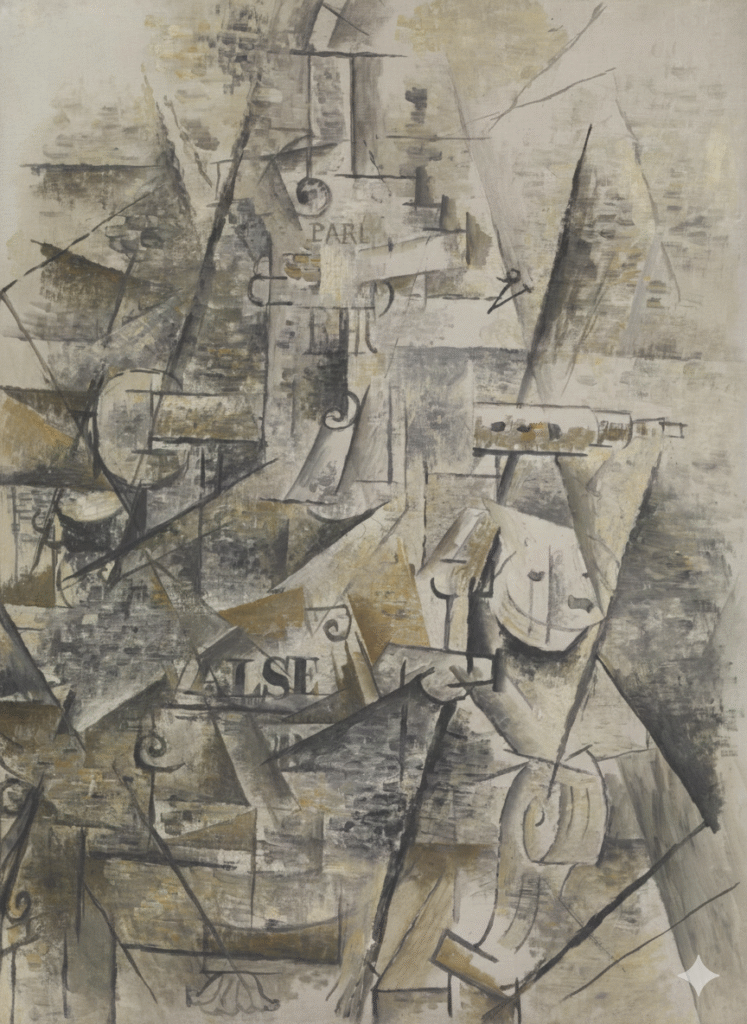

Clarinet and Bottle of Rum on a Mantelpiece (1911) by Georges Braque

Description: Welcome to Cubism, the style that broke everything down. Along with Picasso, Georges Braque invented this revolutionary way of seeing. Instead of painting objects from one single viewpoint, he shows them from multiple angles at once, as if you’re walking around them. In this painting, you can hunt for clues of the objects in the title—fragments of a clarinet, a bottle, and maybe a newspaper on a mantelpiece—all fractured into geometric shapes and muted colors. Braque and Picasso worked so closely together during this period that some of their paintings are almost impossible to tell apart.

What to Look For: This is like an art puzzle. Look for curved lines that might suggest the shape of the bottle or the clarinet. See the letters ‘VAL’ and ‘SE’? These are fragments of text from a newspaper or poster. The limited color palette of browns, grays, and ochres forces you to focus on the shapes and structure of the painting rather than being distracted by bright colors.

Techniques: This is an example of ‘Analytical Cubism’. Braque used oil on canvas, breaking down the objects into geometric facets and planes. He combined different viewpoints into a single image, creating a shallow, ambiguous sense of space. The short, choppy brushstrokes further add to the fragmented effect.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

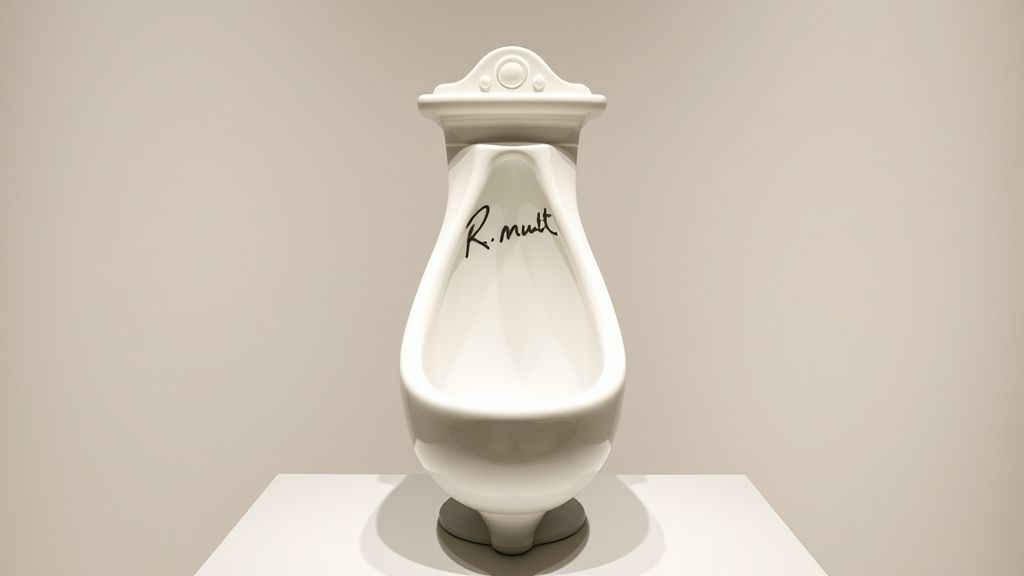

Fountain (1917 (replica 1964)) by Marcel Duchamp

Description: Wait… is that a urinal? Yes, it is! And it’s one of the most important artworks of the 20th century. In 1917, Marcel Duchamp bought a standard urinal, turned it on its back, signed it ‘R. Mutt’, and called it ‘Fountain’. With this one act, he created a ‘readymade’ and changed art forever. He argued that the artist’s idea and choice are more important than the physical object. It’s a work of art that’s all about the big question: What is art? When Duchamp first submitted ‘Fountain’ to an exhibition in 1917, the organizers were so shocked that they hid it behind a partition.

What to Look For: Look at the signature, ‘R. Mutt 1917’. This fake name was a bit of a joke. Also, consider the object itself, a mass-produced item, and think about how placing it in a gallery completely changes its meaning. The art isn’t in the object itself, but in the revolutionary idea behind it.

Techniques: The technique here is not about painting or sculpting, but about selection and presentation. Duchamp chose a mass-produced object and re-contextualized it as art. This is known as a ‘readymade’. The original was lost, so the one you see at Tate Modern is a replica authorized by Duchamp in 1964.

Location in Museum: Main Collection

Estimated Value: Priceless

The Collection’s Significance

The collection at Tate Modern is a spectacular survey of what happens when artists decide to break the rules. Its focus is on international modern and contemporary art from 1900 to today, charting the course of radical movements like Cubism, Surrealism, Pop Art, and Minimalism. Unlike traditional museums that arrange art by date, Tate Modern often groups works by theme, creating exciting conversations between artists from different eras and places. This approach makes visiting a dynamic experience, showing how ideas about life, society, and art itself have been challenged and reinvented over the last century. The museum’s existence in a repurposed power station is a powerful symbol of its mission: to transform the past into a vibrant source of energy for the future.

Final Thoughts on Top 10 Tate Modern Paintings

From the explosive energy of Pop Art to the quiet power of abstract expressionism, a visit to Tate Modern is an adventure for your eyes and your mind. Each gallery offers a new world to explore and a new idea to consider. We hope this guide helps you navigate the amazing collection and find your own favorites among the many Tate Modern, London paintings and artworks. It’s a place that proves art is a living, breathing thing that is constantly changing, and you’re invited to be a part of the conversation.

Plan Your Visit

Opening Times: Daily: 10:00 AM – 6:00 PM. Open late on the first Friday of every month.

Ticket Prices: Entry to the main collection is free for everyone! Special exhibitions require a paid ticket. It’s recommended to book a free timed ticket online in advance to guarantee entry.

How to Get There: Tube: Southwark (Jubilee Line) is a 5-minute walk. Blackfriars (District and Circle Lines) is an 8-minute walk across the Millennium Bridge. Bus: Routes 45, 63, and 100 stop nearby.

FAQs about art at Tate Modern, London

Is it free to visit Tate Modern?

Yes, it is completely free to enter Tate Modern and see the main collection displays. You only need to buy a ticket for special, temporary exhibitions.

How long does it take to see Tate Modern?

You could spend a whole day here! But if you’re short on time, you can see the highlights in about 2-3 hours. This guide to the top 10 paintings is a great place to start.

Can I take photos inside Tate Modern?

Yes, you are welcome to take photos for personal use in the main collection galleries. However, flash photography and tripods are not allowed. Some temporary exhibitions may have different rules.

Is Tate Modern good for kids and teenagers?

Absolutely! The bold, colorful, and sometimes strange art is often a huge hit with younger visitors. The sheer scale of the building (especially the Turbine Hall) is also very impressive.