Picture this: You’re standing in front of Vermeer’s “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” mesmerized by her luminous skin and that impossibly perfect lighting. Now imagine discovering that this 17th-century master might have had a secret weapon – a mysterious box that could capture reality itself and project it onto his canvas like magic.

Welcome to the wild world of camera obscura in art, where centuries-old optical trickery meets artistic genius, and where some of history’s most celebrated painters may have been using what was essentially the world’s first projector. This isn’t just dusty art history – it’s a detective story that could completely flip your understanding of how those “impossible” masterpieces were actually created.

Key Points Summary

- Camera obscura literally means “dark chamber” – think of it as nature’s own projector system

- This ancient optical device has been secretly influencing art for over 500 years

- The Hockney-Falco thesis dropped a bombshell: many Old Masters were tech-savvy innovators, not just skilled observers

- Famous suspects include Vermeer, Canaletto, and possibly even Caravaggio

- The device evolved from room-sized installations to portable “Instagram filters” of the Renaissance

- This technology directly birthed photography and continues influencing digital art today

The Ultimate Ancient Life Hack

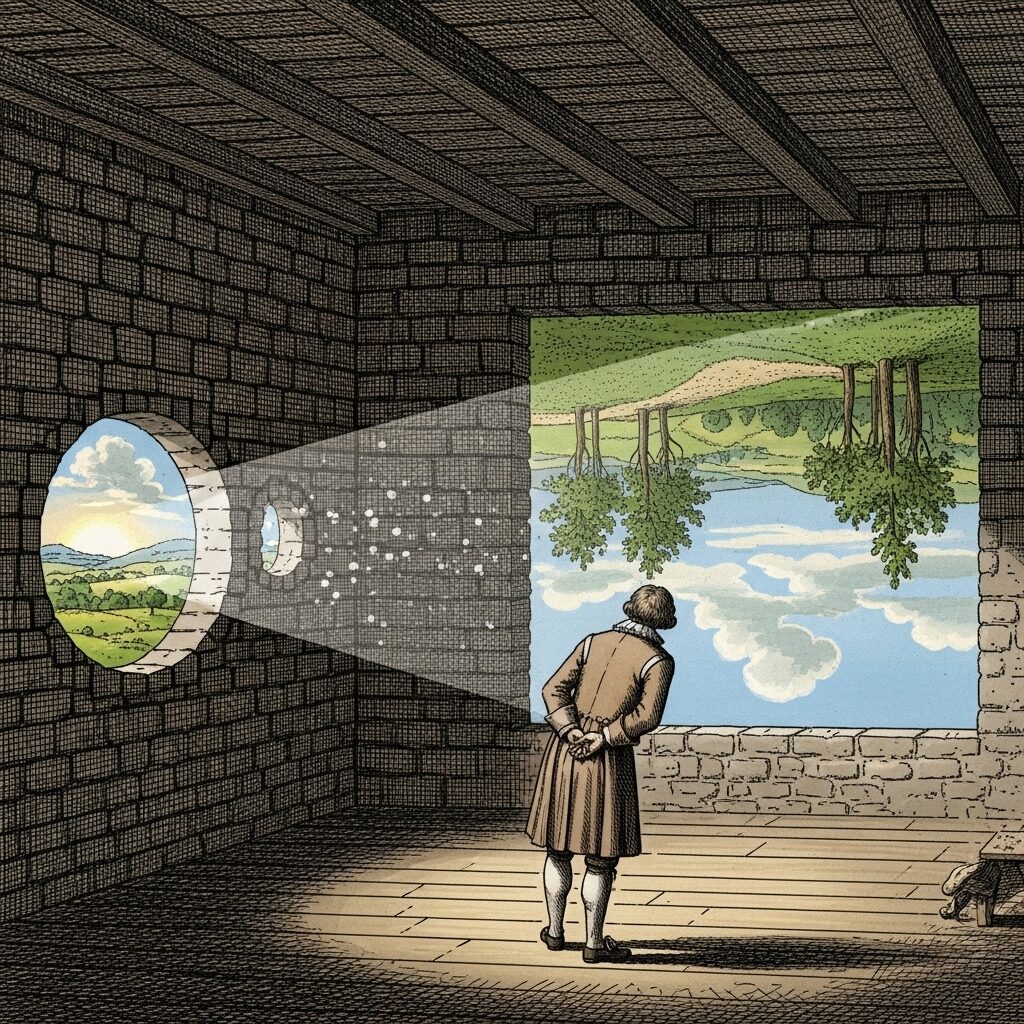

Imagine you’re an artist in 1650, and your wealthy patron wants a portrait so realistic it could fool his mother-in-law. No pressure, right? Enter the camera obscura – basically a dark room with a tiny hole that projects the outside world onto your wall, upside down and in full color. It’s like having a giant, natural television screen centuries before TV was invented.

The genius lies in its simplicity. Light travels in straight lines, so when it passes through a small opening into a dark space, it creates a perfect projection of whatever’s outside. Add a lens to brighten things up, throw in a mirror to flip the image right-side up, and voilà – you’ve got yourself a Renaissance-era cheat code.

But here’s where it gets interesting: this wasn’t cheating any more than using a ruler or compass. It was cutting-edge technology that solved the artist’s biggest headaches – perspective, proportion, and capturing those tricky light effects that make paintings look alive.

From Ancient Genius to Artistic Revolution

The camera obscura’s origin story reads like a thriller spanning 2,000 years. It started with Chinese philosopher Mozi in 500 BCE, who noticed something weird about light passing through holes. Then Arab scientist Ibn al-Haytham wrote the world’s first manual on optics in the 10th century, basically inventing the instruction book for reality projection.

Fast-forward to the Renaissance, and suddenly everyone’s getting in on the action. Leonardo da Vinci was sketching camera obscura designs in his notebooks (because of course he was), and by the 1500s, these devices were the hottest tech in Europe. Artists, scientists, and even entertainers were using them to capture the world in ways never before possible.

The 17th century was when things got really wild. Portable camera obscuras became the Instagram filters of their day – compact wooden boxes that artists could lug around to capture perfect cityscapes and portraits. Imagine being the first artist in your town to show up with one of these bad boys. You’d be like the person who brought the first iPhone to a flip phone convention.

The Conspiracy Theory That Rocked Art History

In 2001, British artist David Hockney dropped what might be the biggest bombshell in art history. Working with physicist Charles Falco, he suggested that many Old Masters weren’t just incredibly talented – they were secret tech users who’d been hiding their optical aids for centuries.

The Hockney-Falco thesis was like CSI for art history. They analyzed hundreds of paintings, looking for clues that screamed “optical device user.” And boy, did they find them:

The Smoking Gun Evidence: Paintings suddenly showed weird distortions that matched exactly what you’d get from curved mirrors and lenses. It’s like finding someone’s browser history – the evidence was right there in the brushstrokes.

The Lighting Inconsistencies: Some masterpieces had multiple light sources or shadows that would be impossible to see in real life but totally make sense if you’re combining different projected images. Busted!

The Scale Shifts: Ever notice how some paintings seem to have different levels of detail, like the artist suddenly got better halfway through? That’s exactly what happens when you move your optical device or change your setup.

This theory didn’t just ruffle feathers – it started a full-scale art world war. Traditional scholars clutched their pearls while others went “Finally, this explains everything!”

The Usual Suspects: Masters with Secret Tech

Let’s talk about the artists who probably had some explaining to do:

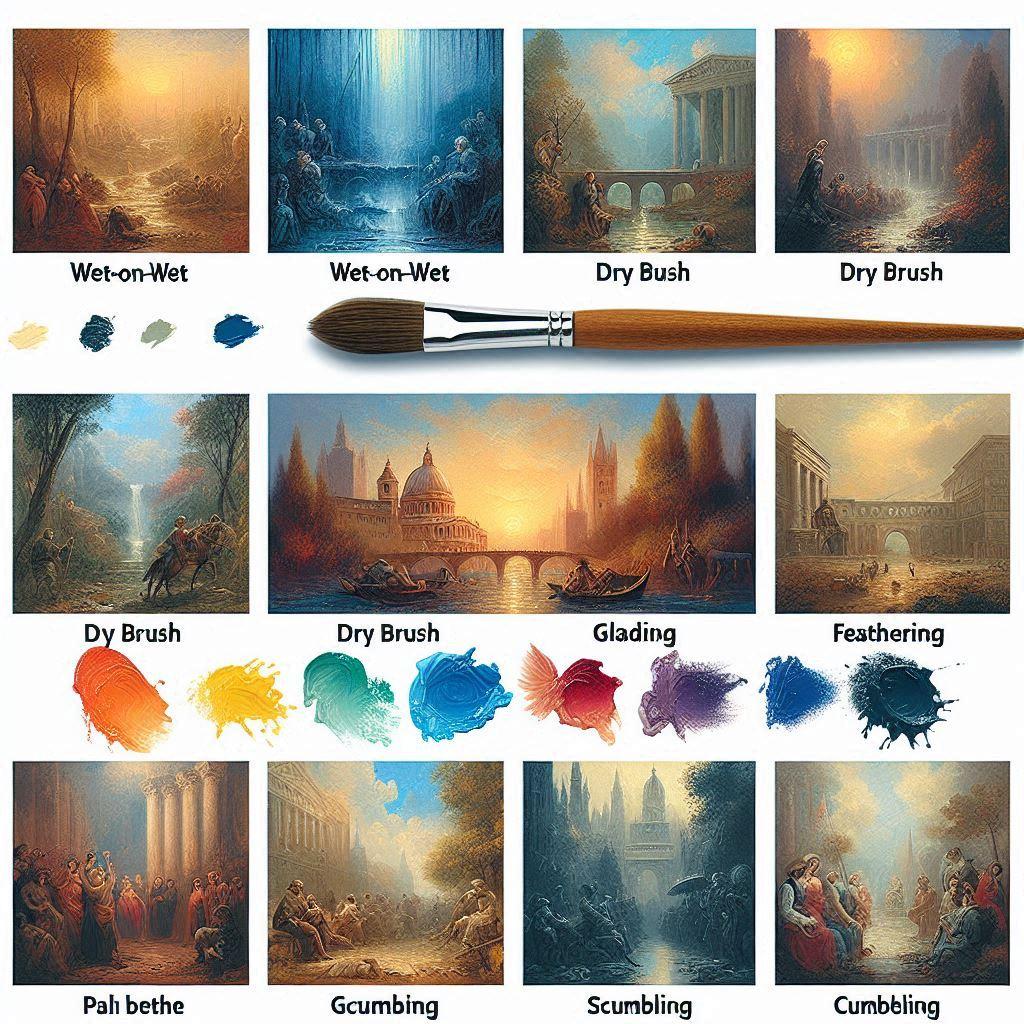

Johannes Vermeer: The Poster Child If camera obscura usage was a crime, Vermeer would be serving life without parole. His paintings show telltale signs everywhere – those distinctive “circles of confusion” in blurry areas, the way light behaves almost photographically, and that impossibly perfect perspective. “Girl with a Pearl Earring” isn’t just a beautiful painting; it’s potentially a 17th-century tech demo. Understanding his techniques enhances appreciation for different approaches shown in famous artist styles.

Canaletto: The Architectural Wizard This Venetian master painted cityscapes so accurate they could be used as blueprints. His Venice scenes show mathematical precision that suggests he wasn’t just eyeballing those complex architectural details. The man was basically Google Street View before Google existed.

Caravaggio: The Dramatic Lighting Genius His revolutionary chiaroscuro effects might have been achieved with optical projection, allowing him to study and perfect those intense light-and-shadow dramas that made him famous. Those dramatic spotlights hitting his subjects? Possibly projected first, then painted with genius-level skill.

The Tech Specs: Camera Obscura vs. Camera Lucida

Think of these as the iPhone vs. Android of Renaissance art tools:

Camera Obscura: The original beast – projects full-color, detailed images but requires a dark room setup. Perfect for landscapes and architectural scenes. It’s like having a home theater system for painting.

Camera Lucida (invented in 1806): The portable version that superimposes ghostly outlines directly onto your drawing surface. No dark room needed, perfect for portraits and detail work. Basically the smartphone version of optical aids.

The camera lucida was revolutionary because it solved the camera obscura’s biggest problem: portability. Suddenly, artists could get optical assistance anywhere, anytime. It was like upgrading from a desktop computer to a laptop.

Why This Changes Everything

The camera obscura didn’t just help artists paint better – it fundamentally changed what was possible in art. Before optical aids, achieving photographic realism required superhuman observation skills and mathematical precision. With these devices, artists could focus on what they did best: choosing colors, creating emotions, and telling stories.

This connects to broader artistic principles explored in the Golden Ratio in Art, showing how artists have always sought tools to achieve mathematical perfection. The smooth light transitions these devices enabled relate directly to techniques like sfumato technique in painting.

The device also solved the nightmare of changing light conditions. Natural light shifts constantly, making it nearly impossible to maintain consistent illumination across long painting sessions. The camera obscura froze these conditions, allowing artists to work at their own pace without chasing shadows across the canvas.

The Modern Connection: From Dark Rooms to Digital Studios

Here’s the kicker – the camera obscura didn’t just influence old paintings. It directly enabled photography, which revolutionized art in the 19th century. When scientists figured out how to chemically capture those projected images, the camera obscura literally became the camera.

Today’s digital artists use software that simulates the exact effects of lenses and optical projection. Understanding traditional color principles, explored in resources like color mixing primer, remains crucial even as technology evolves. The connection extends to cutting-edge developments in AI art generation, proving that artists continue embracing new technologies.

Even traditional painters benefit from understanding optical principles. The evolution of portrait painting through the ages shows how artists have consistently adapted new methods while maintaining their essential creative vision.

The Great Debate: Revolutionary Tool or Artistic Crutch?

The art world is still fighting about this. Purists argue that using optical aids somehow “cheapens” the achievement, like using a calculator on a math test. But supporters fire back: Since when is using better tools cheating? Michelangelo used scaffolding to paint the Sistine Chapel – does that make it less impressive?

The truth is, artistic genius was never about struggling with primitive tools. It was about vision, creativity, and the ability to transform observations into something transcendent. The camera obscura was just another brush in the artist’s toolkit – albeit a really, really good one.

The Bottom Line: Art History’s Best-Kept Secret

The camera obscura story reveals something profound about creativity: the greatest artists weren’t just skilled – they were innovative problem-solvers who used every available advantage to realize their visions. They weren’t afraid of technology; they embraced it.

This ancient device bridges the gap between art and science, showing that the two have always been dance partners rather than rivals. Whether your favorite Old Master used optical aids or not, the camera obscura’s influence on art history is undeniable.

So the next time you’re mesmerized by a masterpiece, remember: you might be looking at the result of artistic genius enhanced by 500-year-old technology. And honestly? That makes it even more impressive. These artists weren’t just painting what they saw – they were using cutting-edge science to see more clearly, then transforming those visions into timeless beauty.

Frequently Asked Questions About Camera Obscura in Art

What is a camera obscura and how does it work?

A camera obscura is an optical device that projects an image of its surroundings onto a surface inside a darkened room or box. It works by allowing light to pass through a small hole (or later, a lens) in one side, creating an inverted image on the opposite wall. The name literally means “dark room” in Latin. Artists used this projected image as a guide for tracing and painting, achieving incredible accuracy in perspective and detail.

Which famous artists used camera obscura?

Several renowned artists are known or suspected to have used camera obscura, including Canaletto, who is confirmed to have employed this mechanical means of recording images. Masters like Rembrandt also used the camera obscura, though other artists may have been more secretive about it. The Delft artists Fabritius and Vermeer may also have experimented with it, though people still debate whether Johannes Vermeer used a camera obscura to capture the incredible detail in his exquisite paintings of domestic scenes.

Did Leonardo da Vinci invent the camera obscura?

Camera obscura was first detailed by artist Leonardo da Vinci, who described a mechanism that would make drawing in perfect perspective easy to achieve. However, he didn’t invent it. Early accounts are provided by Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC), and similar to the later 11th-century Middle Eastern scientist Alhazen, Aristotle is also thought to have used camera obscura for observing solar eclipses. Leonardo was instrumental in documenting its artistic applications.

Why is the camera obscura image upside down?

The image appears inverted because light travels in straight lines. When light rays from the top of an object pass through the small opening, they continue downward and hit the bottom of the projection surface. Similarly, light from the bottom of the object hits the top of the surface. The lens causes the image to flip (or invert) so it’s also the wrong way round, meaning artists using a camera obscura would have to trace the final image in reverse.

How did camera obscura influence painting techniques?

The discovery of this phenomenon set in motion a centuries-long procession of advances in image-making. Given that the finely-detailed image could be traced by the human hand, this optical wonder compelled artists (and scientists) to ask new questions about picture perspective. It revolutionized how artists approached realistic representation, perspective, and lighting in their work.

Is using camera obscura considered cheating in art?

This remains a contentious topic in art history. Some purists argue that optical aids diminish artistic achievement, while others contend that great artists have always used available tools to enhance their vision. The camera obscura was simply another instrument in the artist’s toolkit – like brushes, pigments, or easels – that helped them achieve their creative goals more effectively.

Can you still see camera obscura demonstrations today?

Yes! Many science museums, art galleries, and historical sites feature working camera obscura installations. Some cities even have permanent camera obscura buildings where visitors can experience this centuries-old technology firsthand. It’s a fascinating way to understand how our artistic ancestors saw and captured the world around them.

How is camera obscura related to modern photography?

The camera obscura is the direct ancestor of the modern camera. The principle is identical – both use a lens to project an image onto a surface. The main difference is that photography captures and fixes that image permanently using light-sensitive materials, while camera obscura simply projects a temporary image that artists could trace.

What’s the difference between camera obscura and pinhole cameras?

A pinhole camera is actually a type of camera obscura that uses a tiny hole instead of a lens. The original camera obscura devices used simple pinholes, but later versions incorporated lenses to create brighter, sharper images. Both work on the same optical principle of projecting images through a small aperture.

How did camera obscura change art history?

Camera obscura marked a pivotal moment when art and science converged. It enabled unprecedented realism in painting, influenced the development of perspective techniques, and challenged traditional notions of artistic skill. The device bridged the gap between observation and representation, ultimately contributing to the evolution of both artistic methods and scientific understanding of optics.